Aikido is a modern art founded in the 1920s but its techniques are derivative from older material. With a penchant for hierarchy, Japan classifies its arts as Gendai (new) and Koryu (old) with the Meiji Restoration (1868) as the demarcation line.

A great resource to begin researching Koryu martial arts is >here< and Don Draeger‘s works are classics to own and preserve the information.

I am a firm believer that reading history is invaluable to understand the present. Why? Human nature is a constant – despite cultural differences – and in our particular study, the range of motion and possibilities are limited by the human body. Therefore, a broad reading and appreciation for other arts can lead to a deeper understanding of any particular art.

I would encourage Aikidoists take a close look at the Daito Ryu curriculum as Aikido’s antecedent. All arts have their time and place – meaning many techniques are specific to the weapons, armor, and geography and therefore will have inherent limitations. Put the techniques in their proper context before dismissing them, there may be tips, tricks, and insights that help better develop your own art.

European martial arts (HEMA) are currently in ascendance and some talented people are exploring and revitalizing the western fighting arts. With the proliferation of HEMA, manuals that were once difficult to find are readily available on line.

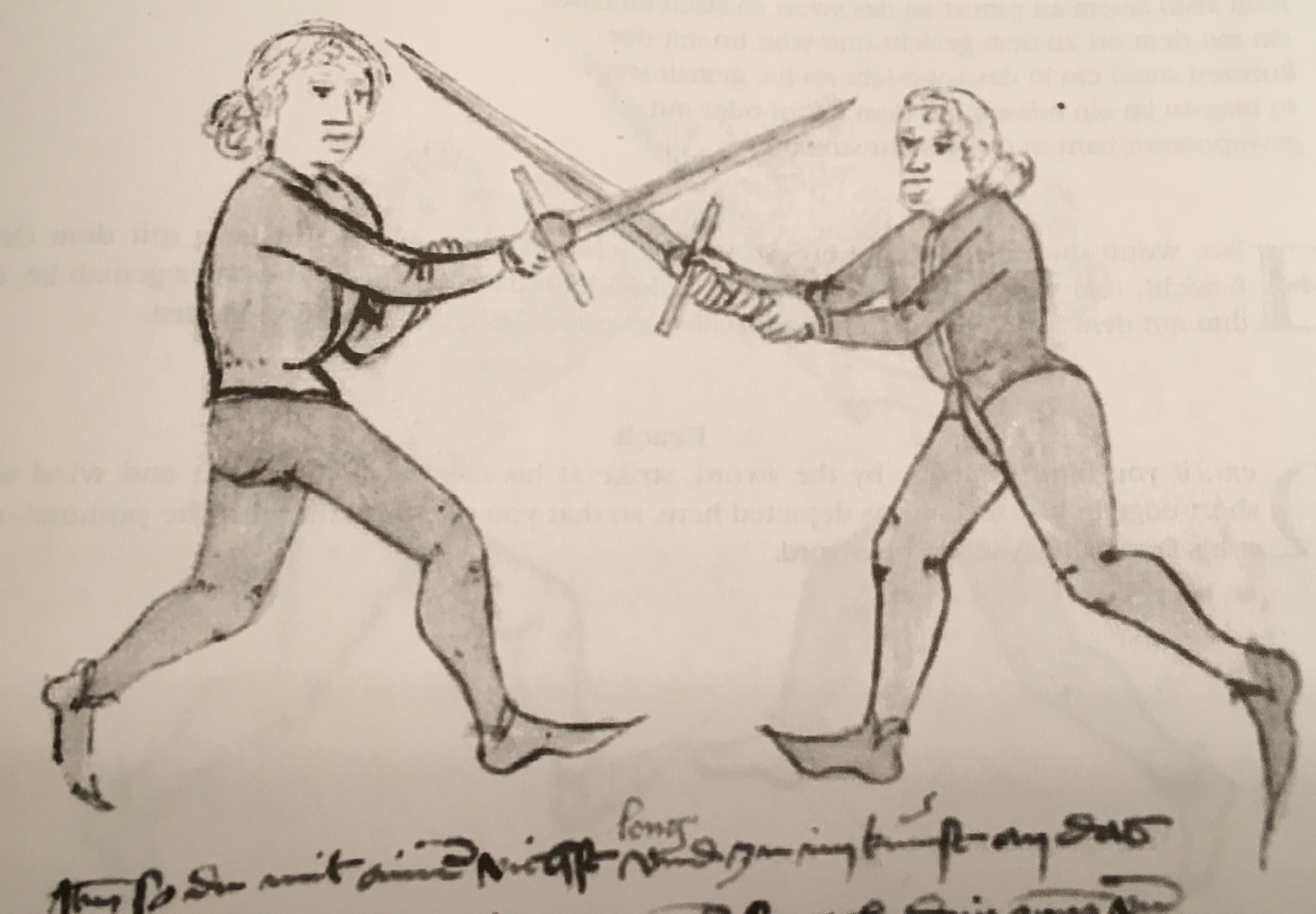

The Codex Wallerstein is a 15th century Fechtbuch (c. 1470) that contains both armed and unarmed techniques.

The opening technique in the codex is a sword technique at distance and is titled “Length”

So you fight against someone, and you come at him at the length of the sword, so both of you are going head to head. Then you should stretch your arms and your sword far from you and put yourself into a low body position so that you have good reach and expulsion with your sword and so that you may attack and defend yourself against all that is necessary. The reach is your standing behind your sword and bending yourself, the distance is in your staying low, as shown here, and making yourself small in your body so that you are great in your sword.

This is not a simple guard, but sound combat advice. You should recognize kiri otoshi (with a longsword) and given the current focus on the foundational kumi tachi – the bunkai should be very familiar…

Review the codex and you will find additional cognates to the kumi tachi we are exploring, but the differences are numerous and should encourage you to ask “why” and “how” are the techniques different. Many techniques result from the design of the weapon and the weapon was designed for a combative purpose – the longsword tried to balance the use of both the edge and the point.[1] So while not all the plates will show you something that readily translates to katana, seeing the differences should be as informative as the similarities.

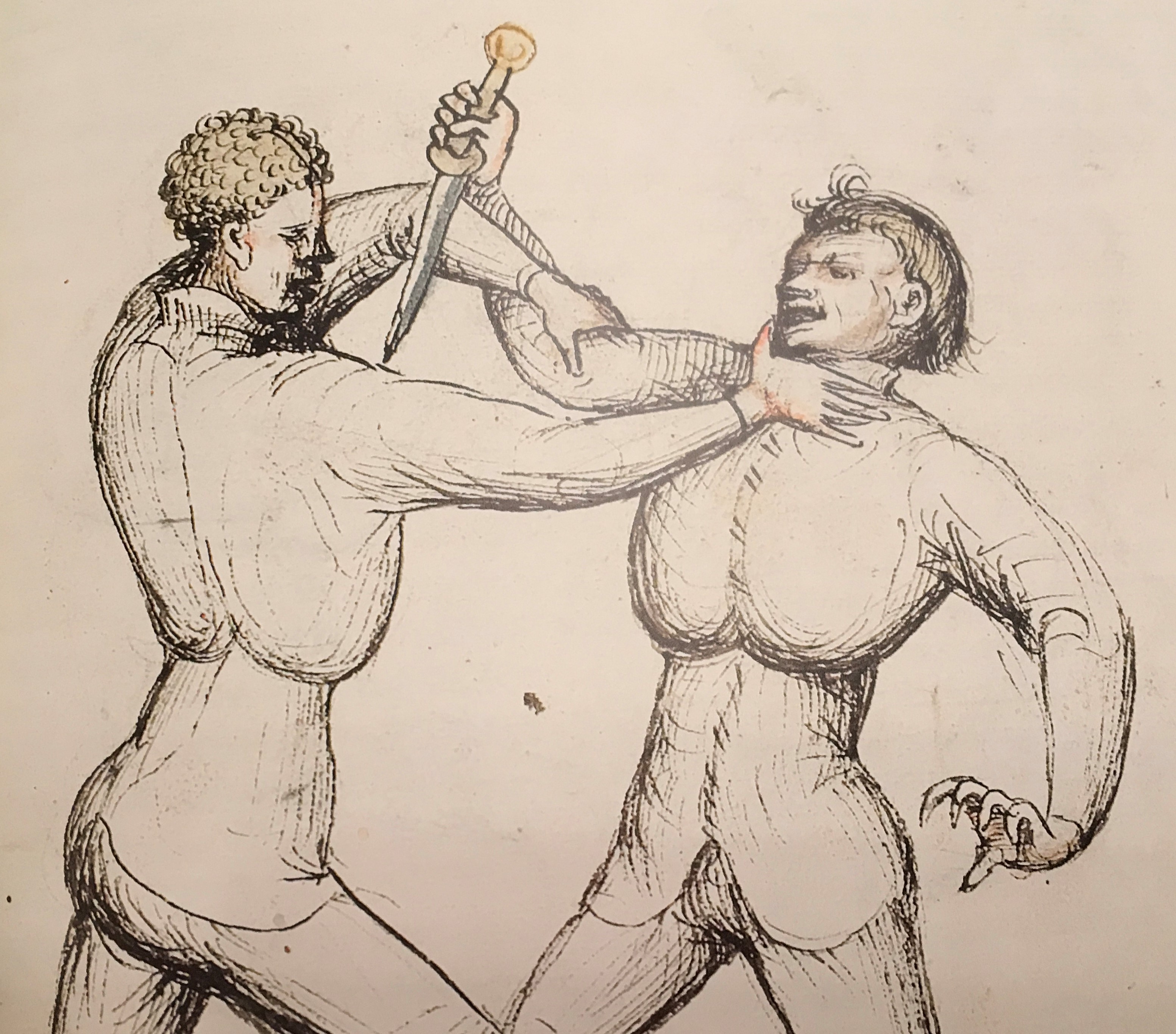

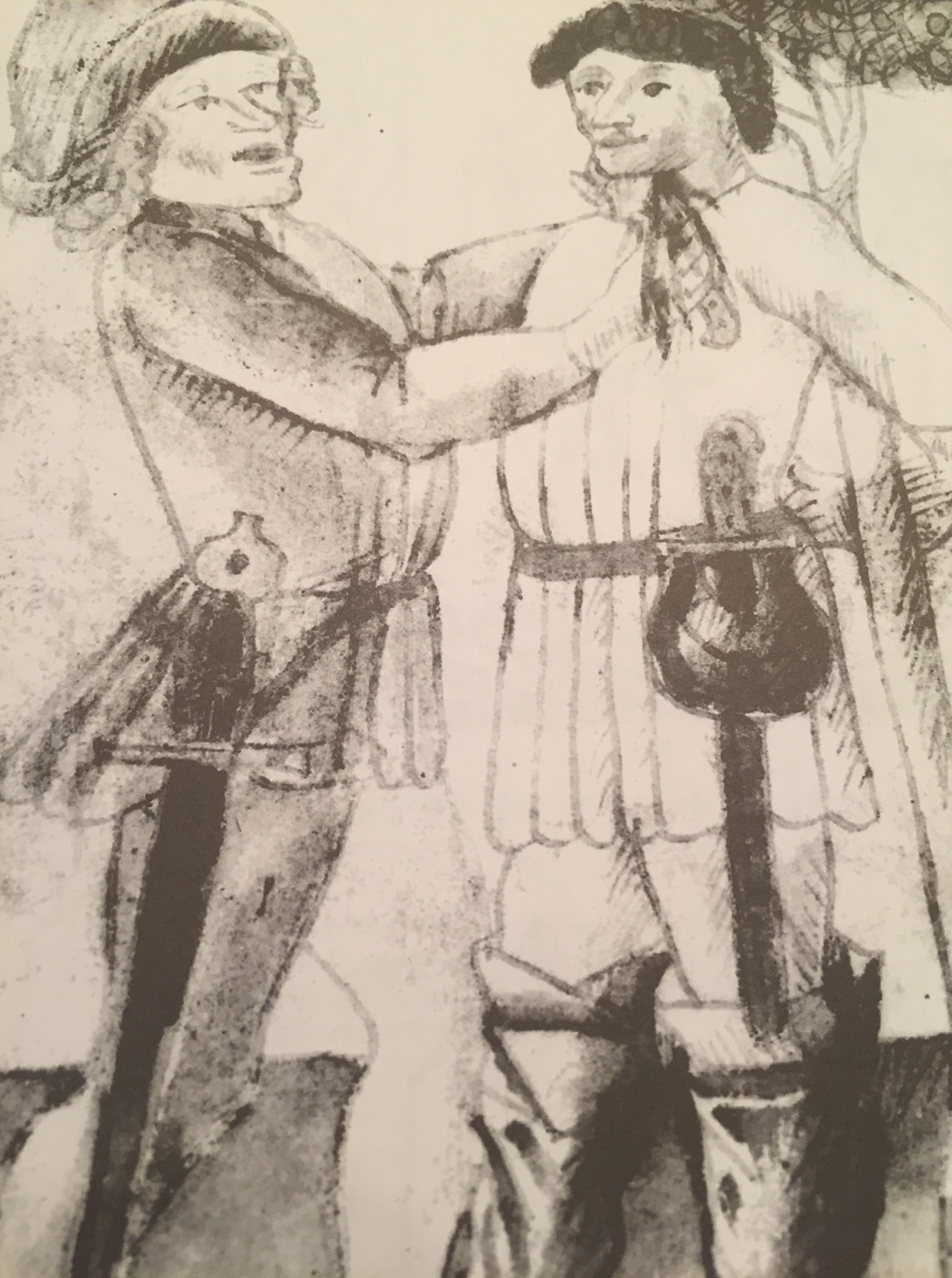

Looking at armed close-quarter techniques the Codex Wallerstein illustrates rondel techniques including the following disarm and leg trap:

The rondel is basically a spike with limited edge making these trap/disarms relatively low-risk, but as I have demonstrated in class, this same disarm is possible against an edged dagger – it just requires more practice. In Der Konigsegger Codex, Talhoffer expands on the use of the rondel.

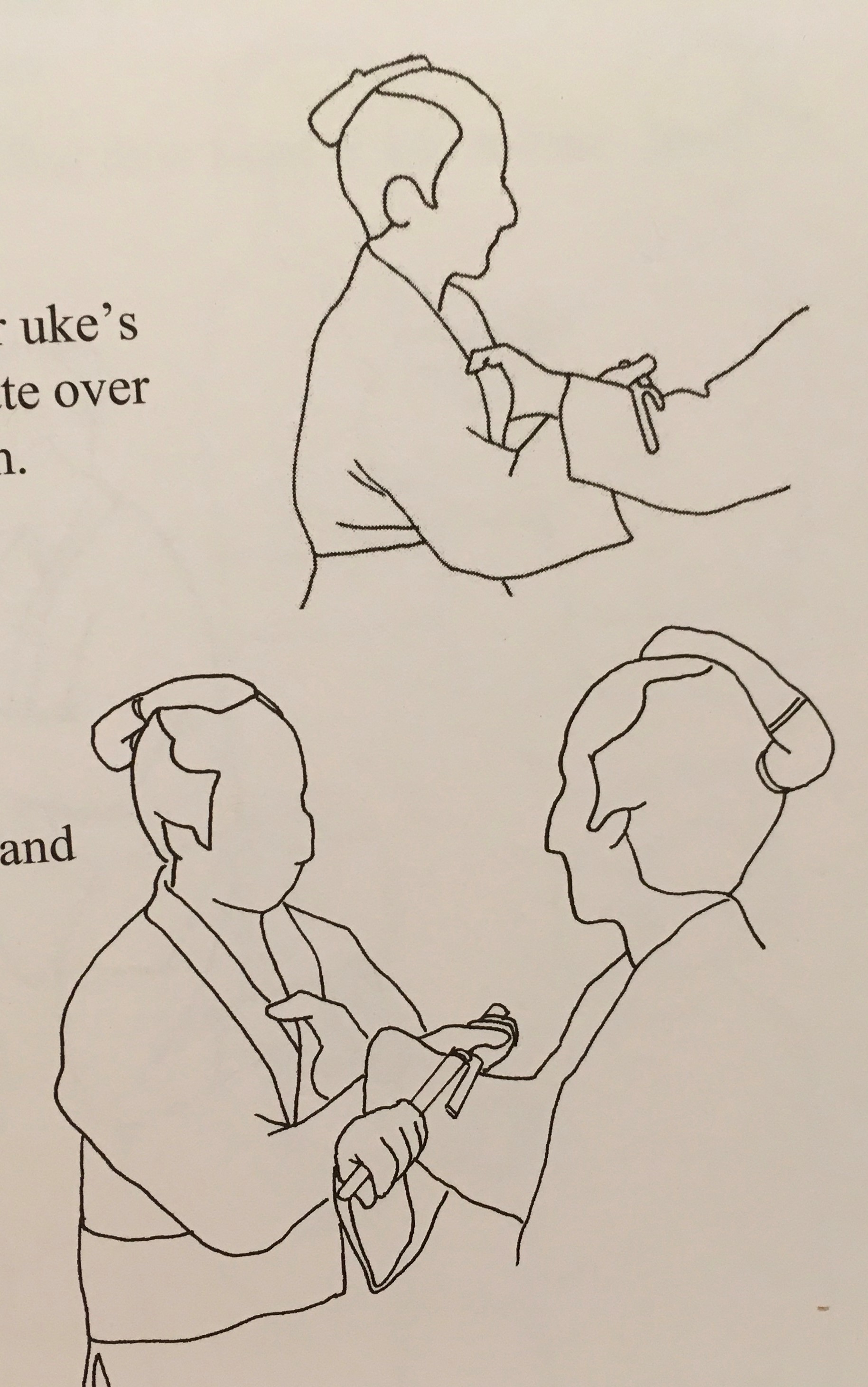

Notice that the techniques are logical uses of the weapon, but are not limited to the specific weapon – rather the general type. There are cognate techniques because the proper use of a weapon of similar types will result in similar uses. A katana and a long sword are similar in length and edge – hence kiriotoshi is logical in each. A rondel is similar to a hanbo, jutte, tessen, cane etc. To see the expression of technique based on a logical use of type of tool, look at the following from Der Konigsegger

And then compare with a taiho-jutsu technique using a jutte:

And this from Masaaki Hatsumi’s Stick Fighting using a simple stick

This is merely a cursory example. A more comprehensive exploration would easily reveal more cognates across time and cultures – but remember that this simple review shows similar expressions from 15th century Germany to 18th century Japan.

And if you look closely enough the unarmed expression of these armed techniques become evident – ude garami without the mechanical advantage of a stick becomes nikkyo.

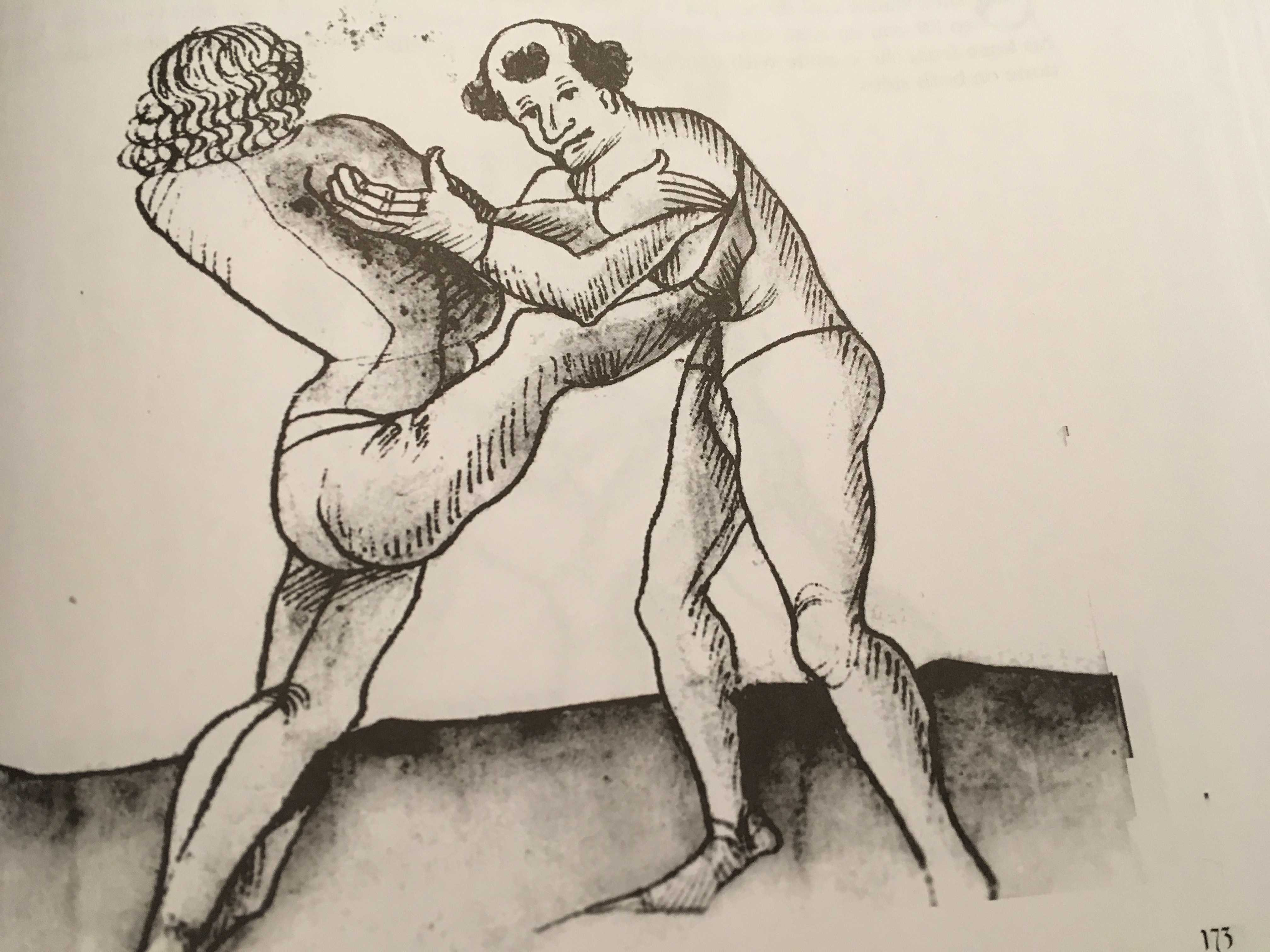

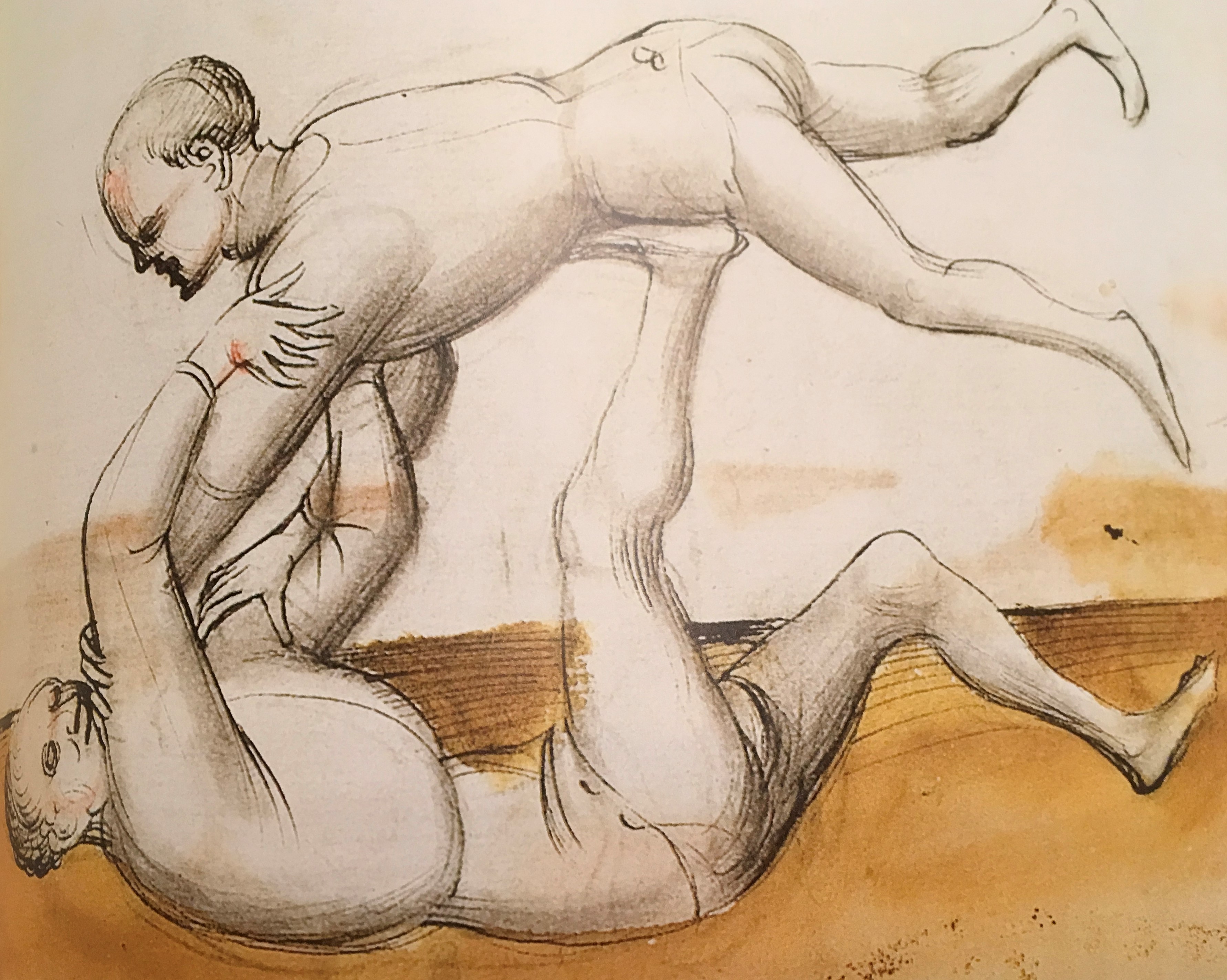

Many of the unarmed techniques appear quite ‘simple’ or ‘obvious’ in the Codex, but the descriptions outline a frank use of the body:

So one more trick: if you want to fight someone by running at him and he is quite strong: boldly grasp him any way you want with a lot of force. When he pulls you with force, put your foot into his stomach and fall down quickly onto your seat: hold your knees close together, as depicted here; and throw him over you, holding his hands tightly so that he has to fall onto his face. You can act with both feet and you should be quick.

I immediately called Plate 81 the “James T Kirk technique” (re-watch the original Star Trek series). The follow-up image is found in Der Konigsegger Codex

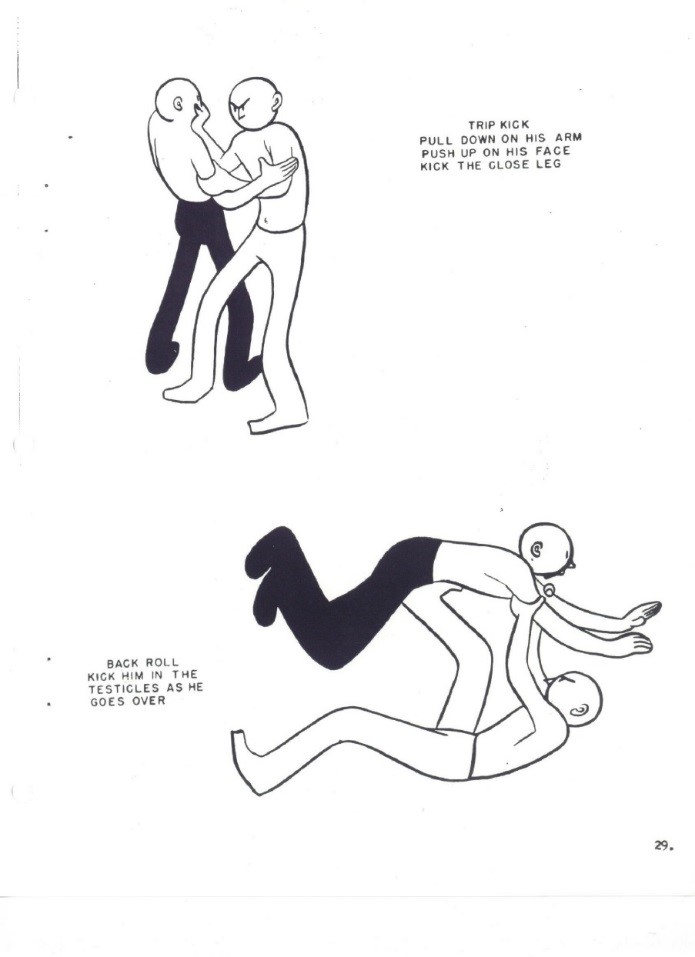

I purposefully selected those techniques that were somewhat amusing – but if you compare these with general combative manuals you will find the same techniques. These are from “Dirty Fighting” by Lt. David Morrah Jr. (1945). [2]

More research will easily reveal more cognates and often the very same technique. Does the same technique imply a direct exchange? While in some cases it may, but I am inclined to believe that the simpler explanation is independent discovery. If your goal is combat effectiveness, then the means and methods will not be difficult to discover.

Some advice is best left in its relevant historical period. The Wallerstein is a very practical manual, and provided a technique to rob a peasant:

At first glance, the illustration appears to depict a simple murder, but the explanation is dryly pragmatic,

So if you want to rob a peasant, pinch the skin on his throat and thrust through it, as shown, so that he thinks that you have cut his throat, and this does no harm.

I love the standards of doing no harm! To the author, this is simple scare tactics: pinch the skin at the throat and make a superficial cut – it may bleed profusely, but will not kill the victim.

Only one plate out of the hundreds shown in the codex describes an overtly nefarious use of martial skill – but one must remember that only the educated elite could afford to own a codex and read the contents. These were techniques for the ruling class. As a compendium of important ‘how to’ techniques (appropriately called ‘tricks’) a majority of the plates describe techniques used exclusively in judicial duels – techniques for trial by combat (including the use of judicial shields). The important skills of robbing peasants, self defense and acquitting oneself in a trial.

Many of the tricks and techniques in the Codex are found in the earlier works by Hans Talhoffer (Talhoffer-Budzin-Tyrone-Artur-Gotha-Codex-1443-transcr-transl), Talhoffer (1459), and Talhoffer (1467)) [An interesting experiment on Talhoffer by John Clements is found >here< and additional resources and links to European manuals is found at the end of the post Thrusting Triangle.]

Each of these manuals and techniques are tied to a specific point in time. Given the constantly changing political landscape in Europe technological innovation was more dynamic than in Japan where the Tokugawa Shogunate was able to impose country-wide edicts, most notably limiting exposure to the west and the proliferation of firearms.

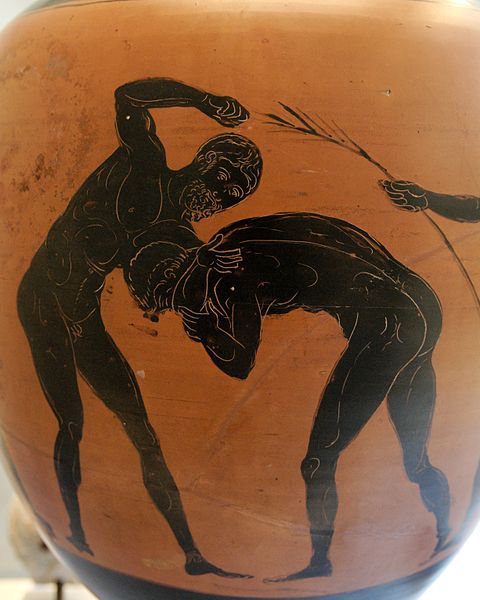

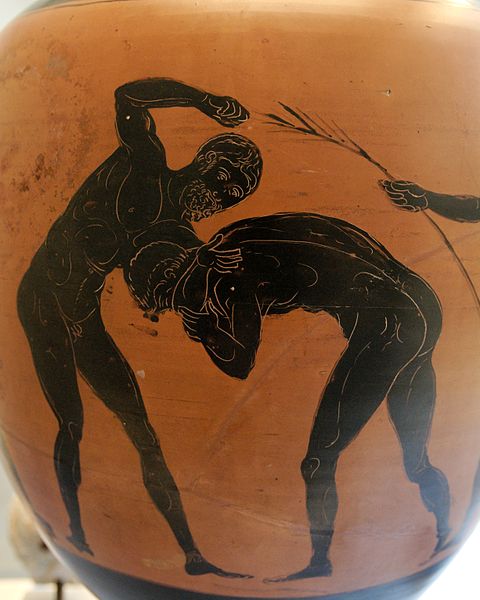

The unarmed arts are more durable – the techniques are much more consistent across time and cultures. Compare pankration with wrestling techniques from the 17th century Petter-Wrestling 1674 with jujutsu. The principles are the same because human physiology is the same and good technique is based on a solid understanding of anatomy and the physics of human motion.

___________________________________

[1] Sword Typology. Ewart Oakeshott’s works are invaluable and set the standard for classifying the types of European swords. Experts may quibble over the details, but review the 1,000 year consistency in the design of the Japanese sword.

Europe was political chaos by comparison over the same time period and the changes in sword design are pronounced. [Brief summary >here<]

[2] Back to the basic eight cuts – here is Morrah’s (Dirty Fighting) presentation of the concept – stripped of any pretext at general concept, as a combat manual he showed only application.

The eight cuts are now reduced to five movements and the point is favored over the edge. Target areas are specified and to reach the targets the point is more effective than the edge with the solitary exception of the trachea.

4 thoughts on “KORYU 古流”