Uncle Jim pointed to a recent article in Science discussing Steven Pinker’s The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (2011). I gave the book a quick read and found it a simple gloss on the benefits of global integration; hopeful homilies of an academician sheltered from the possibilities of violence. Pinker’s general thesis is that the overall rate of violence has decreased significantly over time indicating we are better, more civilized – hence the better Angels reference in the title. And while I admire his sentiment, Pinker’s reliance on big data disguises the most relevant aspects of violence (Nassim Taleb pointed out Pinker’s statistical errors). More importantly, like most academicians of the 1920s and 30s he falls to the arrogant guile of centralized power [1] which is best evidenced by his title, taken from Lincoln’s first inaugural address which betrays Pinker’s naïveté.[2]

Simply stated, Pinker observes that with the end of “the anarchy of hunting, gathering, and horticultural societies” and the rise of agriculture there was a reduction in violence. Centralized authority leading to a reduction in violence? Better academics than I have already pointed out the terrible fallacy here.[3] And I find it ironic (given Pinker’s earlier work on language) that he so baldly shows his prejudice in describing hunting and gathering societies as living in “anarchy.” Without a doubt agriculture lead to an increase in population which allowed (some claim necessitated) centralized authority which then leads to a monopoly on violence. So we have traded raiding for war and vengeance for state sanctioned murder. The scale has changed, but the principle behind the violence has not. We have not become our better Angels, we have just become subjugated. I am not hypocritical enough to ignore the fact that I personally enjoy the benefits of centralized power, but I am too aware of history to naively believe it isn’t simultaneously the greatest threat to our freedom (and the increase in the disparities in wealth).[4]

The fact that we are all statistically far more likely to die in an automobile accident than we are in an act of raw violence is mistaking correlation for causation.[5] Most of us are insulated against direct violence and protected from it by experts in its use. The massively integrated global economy has definite benefits that are increasingly raising the living standards for most of the globe. Combine the overall increase in the standards of living with the amazing decline in the percentage of the population directly involved in food production and the result is passive complacency. Passive because most of us are not directly responsible for our daily survival – we have all traded our varied skills for money which mediates our need to produce for ourselves. Food is no longer a mere necessity for survival but rather a celebratory social engagement. And I am thankful for it! But I am not blind to the fragility of the arrangement.

Having grown up around small-scale farms I remember what it is all too convenient to forget: that most of our protein is provided only after the jugular is slit. Pinker agonizing over torturing a rat as a psychology student is admirably pathetic. Admirable in its sentiment, pathetic in demonstrating how disconnected we are from providing for ourselves. Humans are killers because it is necessary to kill to eat. (Even you vegetarians are destroying life to survive.) That is a basic fact for our species. Modernization can disguise and bury it with specialization and insulate us from it and Pinker misses this ugly truth.

Sitting in a comfortable Harvard office reviewing statistics compiled by others, it is easy to see the macro-trends in the overall decline in death resulting from war as a percentage of the population. His observation is an inane one because he ignores the means of violence. At its core, to kill another human is an intimate interaction. Freud had that right.

We are not, as a species, evolved to be the better angels that big data suggests. Our nature is defined by our responses in crisis. It is precisely the deviations from the mean that we need to address. The fact that most of us will not experience a direct threat to our survival, that most of us will not be subjected to violence, and we no longer need hunt for our larder doesn’t mean that human nature has changed. The need for violence will always be present because violence is the only means to remove a mortal threat. The fact that modern social structures have made wage-slaves of most of us just shows that we willing subjugate ourselves for a modicum of security.

But in the statistical margins we see the persistence of human nature: Buddhist perpetrating genocide on Rohingya, Muslim jihadist extremism, CIA black sites… Violence remains pervasive and is not limited to any religion, culture or time. It remains a persistent human trait. And that fact gnaws on us. The Walking Dead is a brilliant reminder that we are our own worst enemies. Zombies aren’t the threat because zombies have no volition.

So while I am enthusiastic for Pinker’s optimism and revel in the comfort and safety that the modern world provides me, I hold no illusions that our better angels will prevail. History and current events prove otherwise.

It may be relegated to the margins, to the aberrations in the data set, but violence remains real and – impolite as it is to write this: necessary. Necessary because the only counter for violence is superior violence.

Much like table manners had a profound civilizing effect, the cultivation of martial skill civilizes violence. And it is precisely martial skill that we need to understand. Not just the technical “how to” or even the cultural differences “like this” but the more critical understanding of “why?”

The greatest and earliest examples of deep psychology are teaching texts: Gilgamesh and Illiad. Gilgamesh’s transformation after meeting and helping civilize Enkidu and later, his mourning Enkidu’s death and his subsequent quest for immortality shows the higher path. But his quest is fraught with violence. Achilles’ great anger is succored only when he and Priam share the experience of loss. These men did not become great because of their ability to commit violent acts, but because they came to understand violence and its proper use. Violence staves off death and provides the foundation for the edifices of civilization. The life preserving sword. We moderns too easily forget that fact.

Our aspirations to transcend our nature are admirable. The idea of violence as a means of effecting power is trite and a deep study in the martial arts should teach us to become truly better as individuals and that is a personal responsibility.

_________________________

[1] To my thinking, Lewis Mumford’s The Myth of the Machine is a far more subtle and insightful read. Mumford is aware of the benefits and dangers of Leviathan.

[2] Examine the origin of Pinker’s title. Lincoln’s first inaugural address given on the eve of the greatest sacrifice of American blood by the State. The entire speech is a justification for violence perpetrated by a central authority but with clever rhetoric shifting the blame to the polis (Pericles would have been proud to have authored this!) – read the concluding paragraphs (the emphasis is Lincoln’s):

In your hands, my dissatisfied fellow-countrymen, and not in mine, is the momentous issue of civil war. The Government will not assail you. You can have no conflict without being yourselves the aggressors. You have no oath registered in heaven to destroy the Government, while I shall have the most solemn one to “preserve, protect, and defend it.”

I am loath to close. We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.

Thus wars are begun, with the swelling pride of patriots fighting for a Union. Look at the rhetorical flourishes hiding embedded lies (The government will not assail you! Balderdash: mandatory conscription forced many on the battlefield). Our motives may have become more abstracted – fighting for the preservation of the Union and only later the abolition of slavery – but I am not convinced that dying for an abstraction is nobler than fighting over hunting territory. And in the final analysis, the violence remains.

[3] The most frightful omission is the possible impact of a nuclear exchange. Briefly a distant potential, but now one that could dramatically change the statistics of death. A black swan event indeed! Review the links at the bottom of this post.

Perhaps a simple means of reviewing what Pinker is fascinated by. The Economist graphs both the general decline but highlights the important aberrations:

Note the observation, “The countries most prone to wars appear to be neither autocracies nor full democracies, but rather countries in between.” Tease apart that observation and look deeper in time. I am reminded of the Peloponnesian War and those grave conflicts where the largest spikes in death from protracted conflict have been democratic causes. The demos swayed by demagogues resulting in wars like no other (Hanson, 2005).

And this recent post by Tyler Cowen reviewing Only the Dead: The Persistence of War in the Modern Age, by Bear F. Braumoeller, which is largely a critique of Pinker on trends toward peacefulness (Pinker gives only the more optimistic data on Europe). And from the text:

…there is variation in the rate of conflict and war initiation over time, and it’s pretty substantial. Leaving aside the two jumps during the World Wars, the median rate of conflict initiation quadruples in the period between 1815 and the end of the Cold War, after which it abruptly drops by more than half.

The “falling rate of conflict” is thus not entirely reassuring.

How about the deadliness of occurring conflicts?

Analyzing the two most commonly used measures of the deadliness of war, I find no significant change in war’s lethality. If anything, the data indicate a very modest increase in lethality, but that increase could very easily be due to chance…Worse still, the data are consistent with a process by which only random chance prevents small wars from escalating into very, very big ones.

Overall, the arguments in this book are strong, and the discussion of data issues is subtle throughout.

And one massively important variable that has reduced the lethality of combat is medical technology.

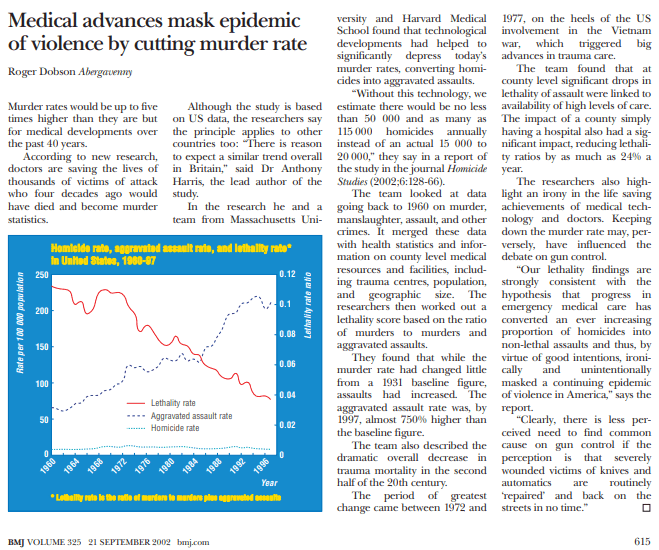

The National Library of Medicine indexed an older (2002) article published in the British Medical Journal.

The article examined long-term trends in violent injury and homicide and the conclusion is sobering in its simplicity: a significant portion of the modern decline in homicide rates is not the result of reduced violent behavior, but of dramatically improved survival rates following violent acts. Advances in emergency response, antibiotics, blood transfusion, vascular repair, and neurological care have radically altered the probability that an assault results in death. What would once have been fatal now often resolves as an injury.

This matters because homicide statistics are commonly treated as a proxy for moral progress. They are not. They are downstream of medical capacity.

Administrative categories record mechanisms and outcomes, not counterfactuals. A stabbing that would have been fatal in 1850 but is survivable in 2025 is no longer counted as a homicide. The violent intent remains; the victim simply survives it. If modern trauma systems were removed the statistics would change overnight without any corresponding alteration in human psychology or social norms.

This is not a pedantic distinction. It goes to the heart of Pinker’s causal claim. A reduction in lethality is not the same thing as a reduction in violence, and neither is proof of moral transformation. It is proof of technological interposition: modern societies have become safer largely because violence has been buffered, managed, and medically mediated, not because it has been transcended.

This helps explain the confidence of modern elites. We live doubly insulated lives. Protected first by institutions that monopolize violence on our behalf, and second by medical systems that erase its consequences before we ever see them. From such a vantage point it is easy to mistake safety for goodness, and survival for virtue.

I admire Pinker’s optimism. I enjoy the world his data describes. I benefit from it daily. But optimism becomes dangerous when it forgets the conditions that make it possible. Institutions that suppress violence are among humanity’s greatest achievements. Right up until they fail. History suggests they always do.

Human nature is not revealed in averages or trend lines. It is revealed under stress, scarcity, and collapse. In those moments, the same patterns reassert themselves with depressing regularity.

Violence remains impolite to discuss. It remains uncomfortable to acknowledge. And it remains, in extremis, necessary. The only durable counter to violence has ever been superior violence, disciplined by restraint, tradition, and understanding.

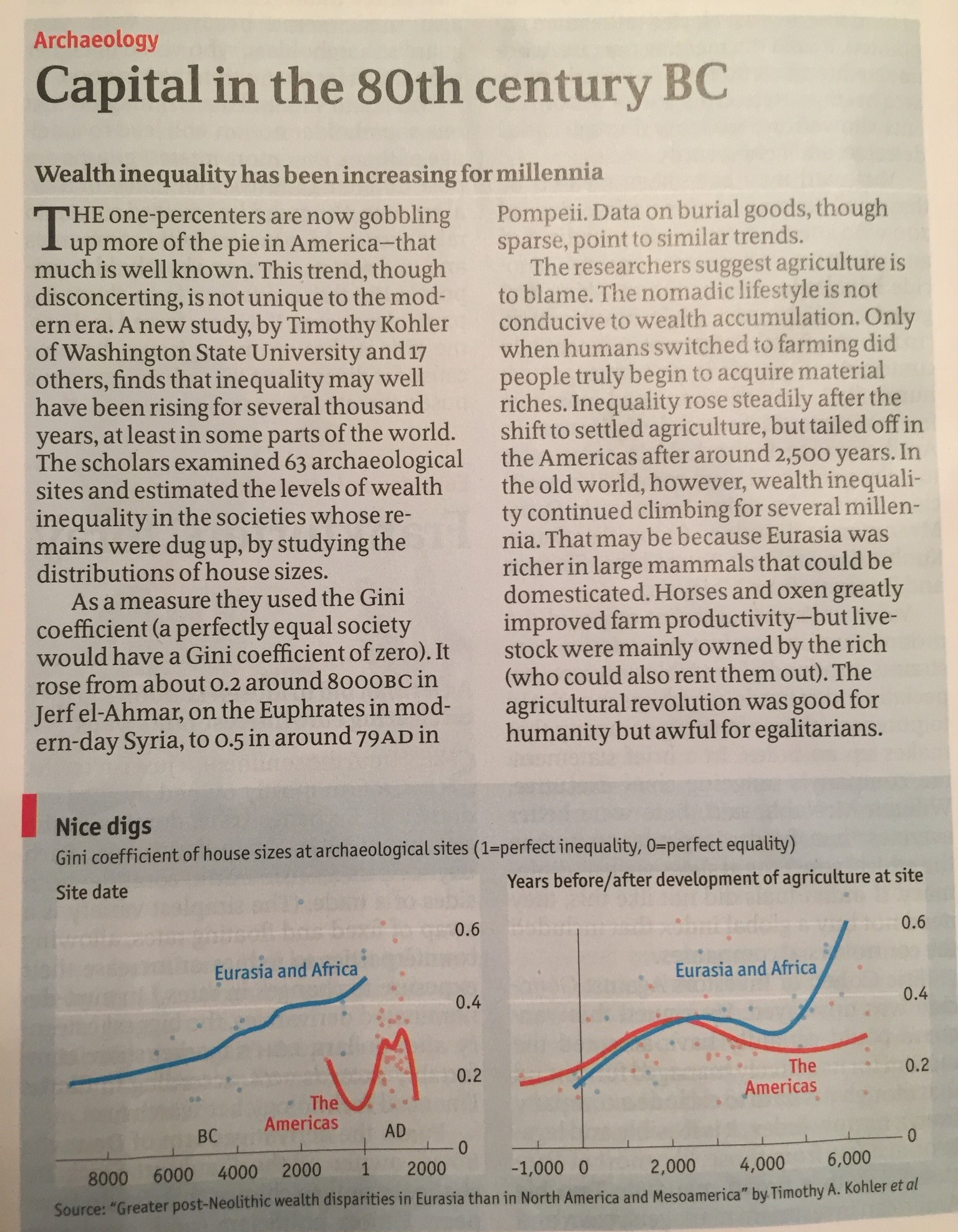

[4] Wealth inequality through time from The Economist – note that while agriculture improved the overall standards of living that there is a trade-off in disparity.

[5] A controversial but statistically convincing explanation for the recent decrease in violence in the United States is the legalization of abortion (Donohue and Levitt 2001). Summaries: Stephen Levitt and Steve Dubner on Freakonomics, and criticisms, and the counterpoint. The underlying logic – those children who would have been unwanted or burdensome to parents unwilling or unable to raise a well-adjusted human are never born and therefore never get to cause predatory violence.

_________________________

UPDATE

The November/December 2019 issue of Foreign Affairs “War is Not Over: What the Optimists Get Wrong About Conflict” is a summary of the nature of geopolitical conflict and has a sobering admonishment:

Above all, overconfidence about the decline of war may lead states to underestimate how dangerously and quickly any clashes can escalate, with potentially disastrous consequences. It would not be the first time: the European powers that started World War I all set out to wage limited preventive wars, only to be locked into a regional conflagration. In fact, as the historian A. J. P. Taylor observed, “every war between Great Powers . . . started as a preventive war, not a war of conquest.”

One thought on “Better Angels”