____________________________

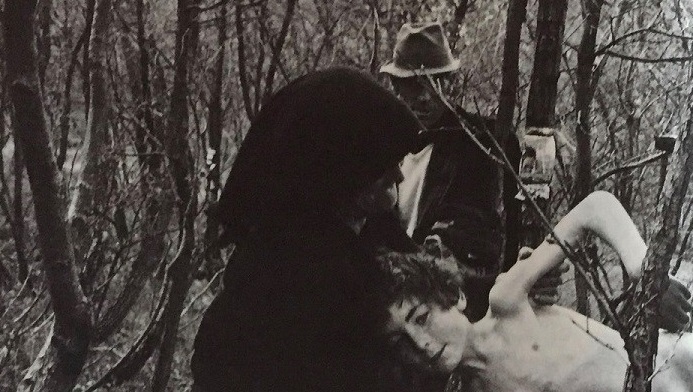

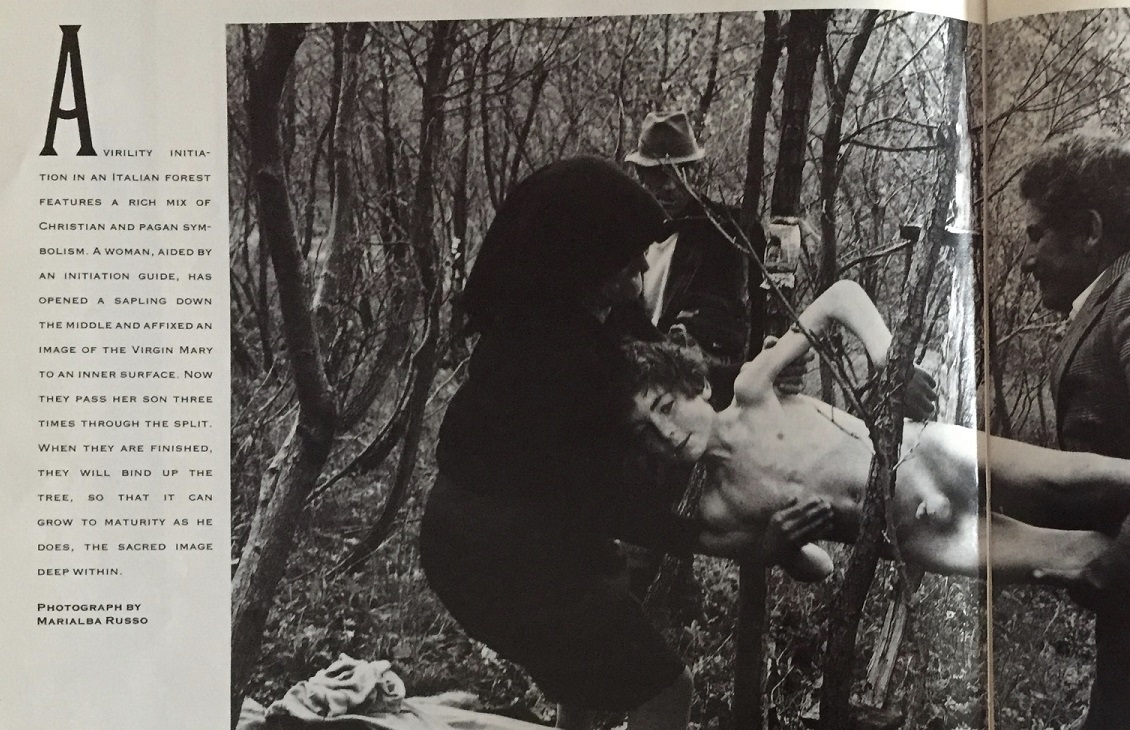

I regret not recording where I grabbed this photograph. I believe it was from Life magazine in the late 1970s, taken by Marialba Russo [1] from her study in virility, ritual, and the human need to prove transformation.

____________________________

The latent anthropologist in me laments the lack of rites of passage celebrating important transitions. Blood rites were once the key: girls to women with first menstruation, boys to men with the first wound in battle – first blood to mark passage into adulthood. Of course we moderns have moved past the social stage when fighting and fucking is all we need to propagate and protect the species – we got too much other shit to learn to be productive members. But biology rages on as the deep undercurrent. Therefore we fumble under the misguided belief we are above our biology.[2] Menstruation is a hygienic inconvenience, male aggression is suppressed and criminalized (rather than nurtured and cultivated).[3] Rites of passage denote dangerous transitions (across the limen) and celebrate the successful emergence into the next stage. (Give Arnold van Gennep a read.)

And so what does this have to do with martial arts?

Testing is a rite of passage. A demarcation of the threshold between who we were and who we must become.

As much as I recognize the importance of these rites, I have never enjoyed officiating them. Given that warning – here are suggestions on:

How to Administer a Test

The ultimate goal of any rite is to ensure that the participant emerges with a new status. That status is both an external recognition by others of the transformation as well as an internalization of a transition – of progression.

Pre-qualify the student.

As a teacher, you should know well in advance that any given student merits a new rank. First there must be the basic psychomotor ability: the student has established through consistent demonstration on the mat the ability to make each of the requisite techniques work. The overall level of refinement and understanding will vary according to level, but the consistency in executing the techniques should be evident from time on the mat. The ability to physically execute a technique at an appropriate skill level is the pre-requisite.

Announce the date.

To ensure that there is an audience, ensure that the date is well publicized. The audience validates the experience. All social events need witnesses. An audience also ensures the appropriate affective environment.

Create a Solemn Atmosphere.

A somber and serious environment sets the stage. Put the room on notice that we are now in a different space. Your job as the test administrator is to create that atmosphere. How? A pointed speech about expectations, or stark silence. Read the mood of the room and purposefully change it. Sit on the side of the mat. Wait several full breaths before moving. Walk purposefully to the far corner to observe the testing area. Bring a clip board to write notes. Present yourself with an air of gravitas. Convey through your very posture, facial expressions and solemnity the seriousness of what you are about to bear witness to.

Ritual Formalism.

People respond to ritual and spectacle. Even those who are intellectually aloof from ceremony cannot avoid an emotional reaction. It is precisely the emotional or affective response you need to elicit.

Call students out one-by-one. Instruct them where to sit so as to create distance between them all. This is to provide them with the space to demonstrate as well as for you to view the students. Ask for ukes to sit slightly behind the testing students. They bow toward the kamiza, the teacher, then each other. The order is the structure. The structure is critical to the ritual.

Calling the Test.

The techniques for each rank are prescriptively outlined. Call them in order so as to allow each student to gain a rhythm. You are not testing to fail. The students should have been pre-qualified as sufficiently skilled for the rank they are testing. Your job is to create the atmosphere and environment where the students affectively feel tested so that they can emerge victorious – then need to feel that they have crossed a threshold.

Administer the test to the ability of the students. If the students (or any one in the group) clearly and consistently fumbles a technique – you can provide a clarifying or guiding statement. If that doesn’t redirect the student, move on to another technique. You do not want to exacerbate failure.

Monitor the aerobic capacity of the testers. When in a test environment, most students speed up and fail to breathe regularly: this is induced stress. As a teacher you need to create a healthy amount of stress (to make the experience ‘real’) but need to monitor the ability of the students. You must test to their limits lest the experience be deemed ‘easy’ so you must administer carefully.

If there is a mixed group – some younger athletic types and some older who do not have aerobic capacity – then have the older students sit while asking the younger to demonstrate more. Let the older students catch their wind without drawing too much attention – keep the focus on the action.

Call the techniques in a grave manner. Drop your voice an octave or two. Present yourself as a mountain (Kagemusha, “A mountain does not move”).

Admonish those testing to complete all techniques, to finish pins, to create proper spacing, to not smile, laugh, or apologize. Do not accept less than their complete attention and concentration.

Never forget that there are those few who know that pain is a teacher. Push them hard before the test and during the test to make the experience real – a true challenge of endurance and commitment.

Closing the Ceremony.

The solemn nature of the beginning must carry through the end. The end of the ritual is the reverse of its opening. Students bow to each other, then the teacher, then the kamiza. As the teacher, you may have been sitting seiza the entire time. Your legs may be asleep. Find a way to maintain dignity when returning to the center of the mat to close the test. Your actions are the final markings of closure. Do not break character or change the atmosphere until you have left the mat. Only then has the ritual ended. Only then can the students return to normalcy.

We have crossed through the liminal to emerge as something new. The belt, the scroll, these are the later symbols of the transformation, markers of distinction, but the affective change happens during the test.

Why This Matters.

If Aikido had real, immediate competition, testing would be unnecessary. Victory or death would mark the passage plainly. In peacetime, however, ritual must supply what combat once provided. We recreate a facsimile of danger to keep meaning alive.

Tomiki Aikido introduced competition to simulate this edge. I respect the experiment but reject the result: Aikido is not a sport. Sport rewards the outcome; budo refines the person. Our testing must therefore feel perilous enough to be real while remaining safe enough to teach.

The absence of ritual leaves a vacuum. In that void, aggression festers into pathology and masculinity collapses into fragility. The rite, properly constructed, does not glorify violence; it domesticates it. It teaches us to bleed with purpose.

We cross the limen, endure the trial, and emerge altered. The ancient machinery still works. The form may change, but the need endures.

______________________

Related Resources.

Mark Manson always has a wonderfully irreverent tone that both belies and emphasizes his salient observations and advice. The testing environment should help foster the student’s sense of development and progress. The inculcation of value internally felt and externally recognized.

_______________________

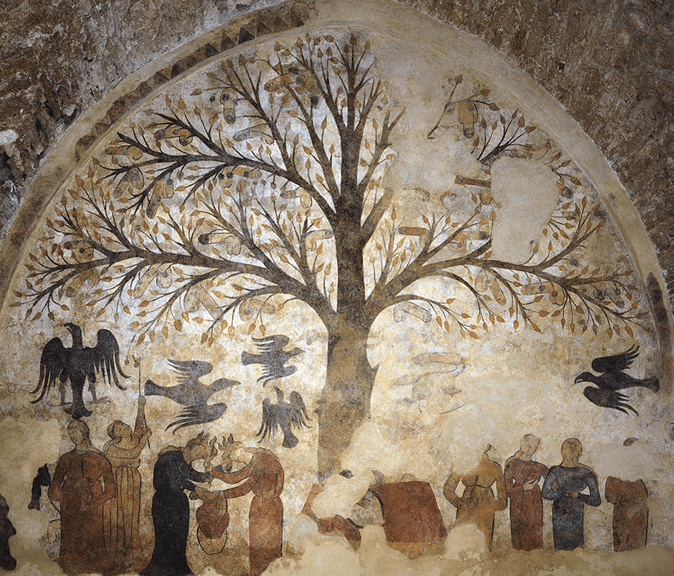

[1] I have done only a cursory search for the “virility” rite captured in the photo. The Italian version is a “passing through” rite, which (in the English folkways) is often associated with medical magic, qv. Hand, Wayland D. “Passing Through: Folk Medical Magic and Symbolism.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 112, no. 6, 1968, pp. 379-492, and this >link< to a folklore account collected in 1886. Folklore studies are not much in vogue. A review of The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne (1789) may prove useful. The virility rite in Italy may have links to the Tree of Fertility in Tuscany at Massa Marittima, Fonte dell’Abbondanza (1265).

Time reports (2011) that the fresco was ‘restored’ without the phalluses. James Frazer’s works addresses the worship of trees.

[2] We arrogantly edit our genetics to suit our cultural presumptions – forgetting Shelly’s warning. He Jiankui opened the door to a new era of eugenics and the illusion of human perfection.

[3] As a man with two boys to raise, my concerns have a strong male bias. I remain resolutely primitive in my belief that most boys need a rough and tumble physical environment to flourish and fear the neutering culture they are surrounded by where these traits are criticized, suppressed and therefore explode in predictably destructive ways. There is a dangerous fragility to masculinity – consider the challenge of male expendability.

One thought on “INITIATION and TESTING”