In the 19th century, anthropology’s great achievement was humility. Cultural relativism and structure-functionalism arose as correctives to imperial arrogance; a way to see “the native” not as savage, but as human within a coherent order. Yet in the 21st century, those same theories can feel dangerous. When all practices are deemed culturally valid, cruelty masquerades as heritage. The Economist ran this story about witch killings in India:

Is there anything so utterly primitive?[1] (Yes, I use that term pejoratively.)

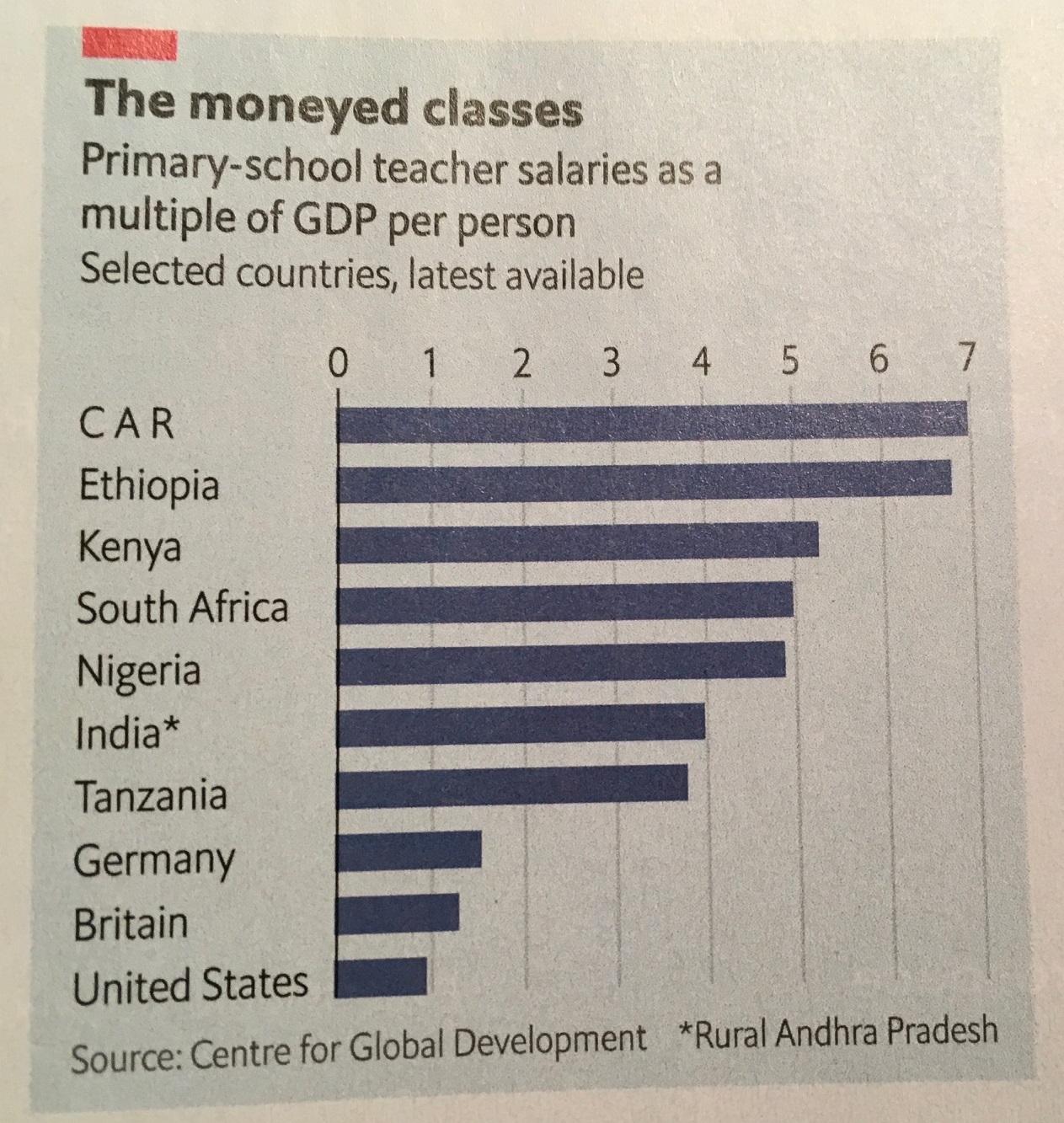

And India, by any measure, values education. According to 2019 data from the Centre for Global Development and UNESCO’s Global Education Monitoring Report, primary-school teachers there earn about four times the national GDP per capita, one of the highest ratios in the world:

In the United States and Britain, the figure hovers around 1.1 to 1.2×. The inverse correlation between national wealth and relative teacher pay is striking: the poorer the country, the higher the social premium placed on teaching. It suggests a tacit recognition that education is civilization’s most reliable lever for progress. Ignorance, it is said, should be forgiven because it shows a lack of access to information. And yet India is a country with a long history respecting education and teachers are demonstrably respected.

And yet ignorance endures. My patience for it wanes with age. I grow impatient for people to be better. Fear of otherness remains universal. Europe trembles at immigration, and demagogues feed on that fear, as John Lukacs warned they would. [2] Populism is the old tribal instinct in new clothes: the need to define oneself as not-them.

And fear is justified by those bouts of violence by the Other: that all-encompassing label for the outsider. And thus we maintain our identities and define ourselves as being not-like-them.[3]

Is Aikido an antidote to such exoticism, the Way of Harmony made literal? Perhaps. One learns to connect with a partner, then with a dojo, a community, a nation, and, by extension, all of humanity. But I am not optimistic. Humanity remains mired in tribal reflexes. What I do believe is that honest training builds character. And character, once tempered, becomes a prophylactic against primitive fear.

John Stuart Mill would have understood. Civilization, he wrote, depends not on conquest but on the moral education of its citizens. To educate is to enlarge sympathy, to make the mind supple enough to recognize another as equal, even when alien. Aikido, in its best form, rehearses that lesson daily: tension without hatred, conflict without dehumanization. Education and practice alike are the disciplines by which we hold the line against relapse. A 19th Century reminder from JS Mill.

_____________________________

[1] Update 10.7.2020 – the persistence of “culture” as a limitation of human progress

Region is a strong predictor of female survival, literacy, autonomy, employment, and independent mobility. A woman with the exact same household wealth/ caste/ religion will likely have more autonomy if she lives in the South.

It does not seem to be a function of wealth, nor was colonialism a major factor. And cousin marriage, which is more prevalent in the south? Alice notes:

Southern women may have gained autonomy despite cousin marriage, not because of it.

Islam, however, is one factor:

In sum, gender segregation became more widespread under Islamic rule. Men continue [to] dominate public life, while women are more rooted in their families, seldom gathering to resist structural inequalities.

But perhaps most significantly:

Female labour force participation is higher in states with traditions of labour-intensive cultivation…

Wheat has been grown for centuries on the fertile, alluvial Indo-Gangetic plain. Cultivation is not terribly labour-intensive, though cereals must still be processed, shelled and ground. This lowers demand for female labour in the field, and heightens its importance at home.

Rice-cultivation is much more labour intensive. It requires the construction of tanks and irrigation channels, planting, transplanting, and harvesting. Women are needed in the fields. Rice is the staple crop in the South.

And this:

Pastoralism may have also influenced India’s caste-system. Brahmins dominate business, public service, politics, the judiciary, and universities. Upper caste purity and prestige has been preserved through female seclusion, prohibiting polluting sexual access. These patriarchal norms may be rooted in ancient livelihoods. Brahmins share genetic data with ancient Iranians and steppe pastoralists. Brahmins also comprise a larger share of the population in North India and only 3% in Tamil Nadu.

Over the centuries, male superiority may have become entrenched.

Finally:

Northern parents increasingly support their daughters’ education, but this is primarily to improve their marriage prospects, not work outside the home.

There is much, much more at the link, including some excellent maps, visuals, and photos.

[2] John Lukacs tried to warn us against this populism. He learned history’s lessons hard and personally. His obituary from the The Times of Israel is copied (with links added) below:

John Lukacs, iconoclastic historian and Holocaust survivor, dies at 95

A biographer of Winston Churchill, the Hungarian-born scholar lamented the erosion of ‘civilization and culture of the past 500 years, European and Western’

NEW YORK (AP) — John Lukacs, the Hungarian-born historian and iconoclast who brooded over the future of Western civilization, wrote a best-selling tribute to Winston Churchill, and produced a substantial and often despairing body of writings on the politics and culture of Europe and the United States, has died.

Lukacs died of heart failure early Monday at his home in Phoenixville, Pennsylvania, according to his stepson, Charles Segal. He was 95 and had lived in Phoenixville since the 1950s.

A proud and old-fashioned man with a prominent forehead, cosmopolitan accent, and erudite but personal prose style, Lukacs was a maverick among historians. In a profession where liberals were a clear majority, he was sharply critical of the left and of the cultural revolution of the 1960s. But he was also unhappy with the modern conservative movement, opposing the Iraq war, mocking hydrogen bomb developer Edward Teller as the “Zsa Zsa Gabor of physics” and disliking the “puerile” tradition, apparently started by Ronald Reagan, of presidents returning military salutes from the armed forces.

“John Lukacs is well known not so much for speaking truth to power as speaking truth to audiences he senses have settled into safe and unexamined opinions,” John Willson wrote in The American Conservative in 2013. “This has earned him, among friends and critics alike, a somewhat curmudgeonly reputation.”

Lukacs completed more than 30 books, on everything from his native country to 20th century American history to the meaning of history itself. His books include “Five Days in London,” the memoir “Confessions of an Original Sinner,” and “Historical Consciousness,” in which he contended that the best way to study any subject, whether science or politics, was through its history.

He considered himself a “reactionary,” a mourner for the “civilization and culture of the past 500 years, European and Western.” He saw decline in the worship of technological progress, the elevation of science to religion, and the rise of materialism. Drawing openly upon Alexis de Tocqueville’s warnings about a “tyranny of the majority,” Lukacs was especially wary of populism and was quoted by other historians as Donald Trump rose to the presidency. Lukacs feared that the public was too easily manipulated into committing terrible crimes.

“The kind of populist nationalism that Hitler incarnated has been and continues to be the most deadly of modern plagues,” he once wrote.

He belonged to few academic or political organizations and was unafraid to challenge his peers, whether Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., Hannah Arendt, or British historian David Irving. In “The Hitler of History,” published in 1997, Lukacs alleged that Irving was sympathetic to the Nazis, leading to threats of legal action from Irving and the removal of passages from the book in England. In recent years, Irving has been widely condemned because of his ties to Holocaust deniers.

Hitler and Stalin were Lukacs’ prime villains, Churchill his hero. Lukacs wrote several short works on Churchill’s leadership during World War II, focusing on his defiant “Blood, toil, tears and sweat” speech as the Nazis were threatening England in May 1940. Lukacs wrote that the speech was at first not well received and that instead of having a unified country behind him, Churchill had to fight members of his own cabinet who wanted to make peace with the Nazis.

“If at that time a British government had signaled as much as a cautious inclination to explore a negotiation with Hitler, amounting to a willingness to ascertain his possible terms, that would have been the first step onto a Slippery Slope from which there could be no retreat,” Lukacs wrote in “Churchill: Visionary. Statesman. Historian,” published in 2002. “But Churchill did not let go; and he had his way.”

One Churchill book attained unexpected popularity after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. Rudolph Giuliani, then New York City’s mayor, held up a copy of Lukacs’ “Five Days in London,” declared he had been reading it and likened New Yorkers to the citizens of London.

Quietly published in 2000, the book jumped into the top 100 on Amazon.com’s best-seller list. But Lukacs was not entirely grateful. He noted that “Five Days in London” had little to say about how Londoners endured the Nazi assault, and he rejected comparisons between London in 1940 and New York City in 2001.

“The situation was totally different,” he told The Philadelphia Inquirer at the time. “As a matter of fact, it was much worse in England.”

More recently, “Five Days in London” was widely cited as a source for “Darkest Hour,” the 2017 film starring Gary Oldman in an Oscar-winning performance as Churchill.

The historian was born Lukacs Janos Albert in Budapest. Lukacs had a Catholic father and Jewish mother, making him technically a Jew, although he was a practicing Catholic for much of his life. For the Nazis, who occupied Hungary in 1944, being half a Jew was enough to be sent to a labor camp.

By the end of 1944, he was a deserter from the Hungarian army labor battalion, hiding in a cellar, awaiting liberation by Russian troops. Within months of living under Soviet control, he fled the country on a “dirty, broken-down train” to Austria. In 1946, he arrived by ship in Portland, Maine, his youthful affinity for communism shattered.

Lukacs was a visiting professor at Princeton University, Columbia University and other prominent schools, but spent much of his career on the faculty of the lesser-known Chestnut Hill College, a Catholic school (all girls until 2003) in Philadelphia where he taught from 1946-1994. He was married three times (his first two wives died) and had two children.

A pessimist by definition, he often expressed personal contentment. He wrote warmly about his enjoyment of romance, friendship, books, teaching and the rural life, the “pleasure of fresh mornings, driving alone on country roads, smoking my matutinal cigar, mentally planning the contents of my coming lecture whose sequence and organization are falling wonderfully into place, crystallizing in sparks of sunlight.”

“Because of the goodness of God,” he concluded in his memoir, “I have had a happy unhappy life, which is preferable to an unhappy happy one.”

__________________________

[3] Yet that right of self-determination and definition is a sacred right. The very definition of sovereignty. Look to the Sentinelese in their vigorous defense of their island. Survival International actively protects the Sentinelese’s isolation and both India (which has jurisdication) and the United States both refuse to prosecute the killing of misguided missionary John Chau. Is this the origin of the Prime Directive from Star Trek?