When I began training, I was told that the minimum time commitment to earn shodan in Aikido is to train three classes per week for a period of five years – and this presumes progress through time on the mat under competent instruction with honest training partners. If you do the math, however, the USAF requirements indicate that just under seven years would be required at the three-class per week minimum.

For many people even that level of dedication is difficult. We are pressured for time with work, family commitments, and entertaining distractions. Training is something we fit into the schedule. Yet training time is critical to development.

And I don’t mean just showing up to train. Time on the mat is only one metric to measure progress and not always a good one. One needs to actually learn from their training time on the mat. As Bruce Lee observed, perfection may be the goal, but the real question is, “For what level of imperfection will we settle?”

Every time we step on the mat we have the opportunity to improve. Training with a partner is a gift. With good training, each player gives the other the ability to elevate their skills through honest feedback (physical more importantly than verbal). Time on the mat with a partner is without a doubt the most effective way to learn the art because you have an instant feedback mechanism. You can each help train the other to somatically feel the progress.

Solo training is a way to augment and accelerate your basic skills. The math is simple – ten minutes of solo training a day adds over 60 hours of training time per year, when done effectively.

To maximize the benefit, focus on isolated skills and physical development that may be outside the everyday norm – for example shikko and shinkokyu. Shikko is an unfamiliar body mechanic for many of us and shinkokyu is a way to learn to be grounded. Both basic patterns of movement are absolutely necessary to master, but are too rote and repetitive to take time away from training and practice on the mat. Master them by mindfully practicing solo. Do you stand at work? Subtly shift shinkokyu to get in repetitions. Practice moving from standing to shikko to walking while at home. Tenkan around obstacles in your house.

Have very specific goals. Practice your sword cuts. Do 100 shomen strikes per day. Then move to yokomen, then tsuki, etc. It is important to be mindful, but at the beginning simply do the cuts. Keep at it, as you develop stamina, your goal will be to develop proper form. Incrementally add the number of consecutive cuts per day but the goal is to get to 1,000. It is impossible to do 1,000 cuts wrong – meaning if you can do 1,000 consecutive cuts, your form must be correct because you have gone beyond physical limitations.

Importantly, employ proper visualization. Professional athletes use visualization techniques to improve performance and there are programs happy to teach you how to better visualize. For me, visualization entails recalling the patterns from inspirational teachers and by envisioning weapon to target strikes. Create linkages, find the smoothest path from target A to target B, move along the crispest tangent, or the tightest arc to minimize your movements. Or simply follow a scripted routine each morning to encourage a relaxed but ready state.

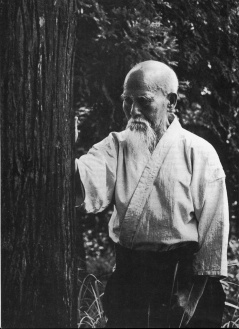

O’Sensei tiesho – compare the shoulder/breath relaxation exercises with those from Systema.

There are any number of discrete skills that can (and should) be practiced solo daily. Here are some suggestions in addition to those mentioned earlier:

Attacks: jodan/chudan/gedan tsuki; shomen/yokomen/gyaku yokomen; use empty hand and weapons (ken/jo/tanto).

Strikes: once the attacks are familiar – try hitting a pell with your weapons and the bag empty handed. Hit speed bags and heavy bags alike. Use a makiwara, or my favorite >Bob<. Steal a variety of strikes from other arts (for example: Systema relaxed strikes).

Movement: ashi-sabaki; tenkan; ushiro tenkan; suriyage (grapevine) footwork.

To break it down, think of practicing those elements of movement that can be done independent of a partner. The most obvious should be suburi in general. Suburi is essentially about repetition and then more repetition. The point of extended repetition is to force the body to figure out how to use a weapon efficiently – just keep swinging the weapon and you will be closer to the most economical path of motion. Suburi is faster and more fluid than kihon patterns.

Kihon movements are the fundamental building blocks – and some can be done independently of a partner. Kihon are prescribed and idealized movement patterns – closer to kata than energetic actions. Kihon should be done slowly enough to allow full intellectual processing of the movements – a high level of reflexive awareness. Follow this line of reasoning and you may develop heretical thoughts like adding kata to Aikido.

Just remember: because the ultimate goal of Aikido is to connect, to have an energetic exchange, solo training can only be a supplement and not a substitute for time on the mat. Nor are videos a means to replace competent instruction under a qualified teacher.

Keep Training!

___________________

Harder than it seems – try using a silk scarf to augment your solo training

_______________________

I have suggested earlier that re-contextualizing the movements is also a key to effective training. By classifying techniques in a matrix and by re-presenting techniques through narrative or graphical depiction is a means to better understand the material. Just remember your classifications will be an indication of your particular context and dispositions. An amusing aside to illustrate the point: In 1238, Alfonso X of Castile published Libro de los Juegos – The Book of Games. The book classified games according to categories sensible to his kingly status: games played on horseback, those played dismounted, and those played while seated.

5 thoughts on “SOLO TRAINING”