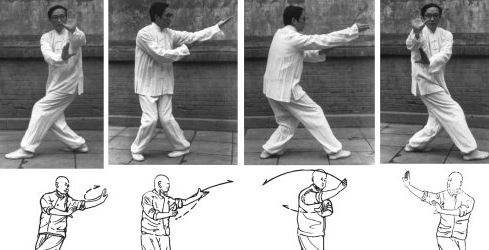

For some time now, I have incorporated a basic hand and body exercise into my “warm up” sequence from Bagua Zhang – “opening hands” (see 3:36 for a reminder).

The Bagua movement in isolation may seem awkward at first. I present it as a global body movement adding trunk and hip rotation and done one side at a time.

Why?

Learning a patterned movement sequence in isolation is good solo training especially when you can see that the flow pattern is irimi nage when using the head as the lever, and kotegaeshi when using the wrist.

Go through the motion solo: it is a circular dissolve. Now envision performing yokomen-uchi kotegaeshi. The Bagua will lead you to intercept the strike, control uke’s line to your center, then the wrist roll to the lock / disarm. Move up the body line and take the arm above the elbow and the pattern leads to irimi nage omote. Move higher still to the head and it becomes a neck break. Same pattern of motion resulting in three techniques.[1]

The nuances of each interaction requires explication in the dojo, but abstracting to and discussing the principles (the potentials) of the movement as a concept is its power. Same pattern, just different ranges as you move up the body from distal to core.

This leads us back to ranges of combat. Aikido is a ‘long range’ art because the weapons used to inform its principal techniques were long: the katana, bayonet, and to a lesser degree the wakazashi and tanto.[2]

Longer weapons extend the range of combat but they have the effect of necessitating using the musculature of the core. As a generalization, the longer the weapon, the larger muscle groups required to deploy it.

Hence, the weapons in Aikido are deployed two-handed. And because the tanto is used to pierce armor, it is used not as a knife, but rather as a spike.

The point is: Aikido’s range has been defined by its weapons and its development of the tanren (core) is a logical byproduct of the type of body engagement needed to effectively deploy and counter the weapons used.

Note that this is a rather specific development to a cultural point in time and therefore just one data set in investigating the range of human motion. Hence using a Bagua exercise to find the principle and potential of the movement rather than focus on the specifics of technique.

Change the weapons and the ranges change dramatically. I default to the Philippines where the confluence of Spanish and Filipino cultures preserved useful distinctions of range.

The family of Filipino Martial Arts (FMA) is essentially, Eskrima which is derived from Spanish esgrima, “fencing,” Arnis – short for arnés de mano, Spanish for “harness of the hand,” and Kali which may derive its name from the karis (kris), or a combination of the Filipino words for body (kamot) + motion (lihok).

The named ranges generally are largo, medio, and corto.

- Corto Mano: close range, short movements, minimal extension of arms, legs and weapons, cutting distance

- Largo Mano: long range, extended movements, full extension of arms, legs and weapons, creating distance[3]

- Medio Mano: medium range, splits the difference (and often involves a long + short weapon: espada y daga)

The technical nature of combat changes as the distance between opponents changes and will have specific techniques to contend with those variables of time, distance and speed.

But in this brief review I want to emphasize one point: that by seeing the conceptual power of a pattern of movement one can deploy the same movement to solve for the problems created at various ranges.

Virtūs et Honos

________________________

[1] Review

[2] The typical dojo wood tanto is too short. The traditional blade length was between 6 to 12 inches. The typical wood tanto in the dojo is about 11 inches in total length.

[3] Good insights into the Largo Mano variables and strategies and connections to Western fencing.