___________

There are several permutations of the story. A Zen-priest is asked to provide a blessing, and he obliges, “Father dies, son dies, grandson dies.” The beneficiary is confused and angry, “What kind of blessing is THAT?!” And the wisdom is revealed: “Would you rather it happened another way?”

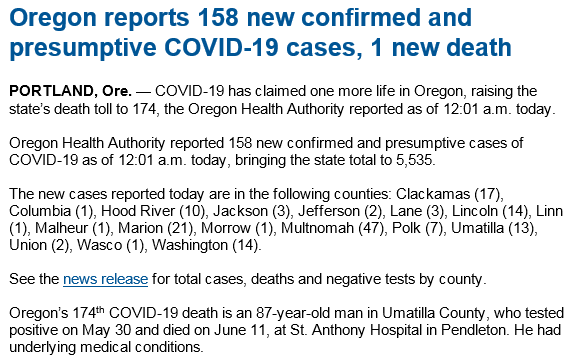

With the received wisdom of the natural order, I submit that the continued sequestering in Oregon is nonsense. The official posting for today (6/13/2020):

Grandfather with underlying medical conditions dies. Possibly a sad event, but depending on the underlying medical condition, probably a blessing! Americans have always confused life extending technology with quality of life.[1] Just because you can do a thing doesn’t mean you should do a thing. For Fuck Sake People – we now have sufficient data to make a rational decision here! Those most at risk are those near the end of life. We are all held hostage to “save” the elderly with pre-existing medical conditions? My recently dead father knew the difference between quantity and quality of life, and given the choice, would gladly have risked accelerating his death for benefit of his grandchildren, and probably even yours, because he knew that quality of life was more important than quantity of time.

My children are staring down the imminent possibility of a no-contact-sport, no-in-classroom instruction year. Stultifying conditions for their development into fully actualized adults. How is that social cost justified? To save the essentially-dead and non-contributory? Yes, it has to be said: not all life has equal value. That is why there is medical triage and actuarial tables. If we want to play this metaphor that we are at war with a virus, then we need to have the testicular fortitude to accept the increased death rate of the marginal to save the sanity and economic future of the majority. That is the calculus of war. The media needs to understand the metaphor it uses. War isn’t hiding in the castle; that is being besieged. You cannot win by defending! Prevailing requires active engagement: taking risks and accepting consequences.

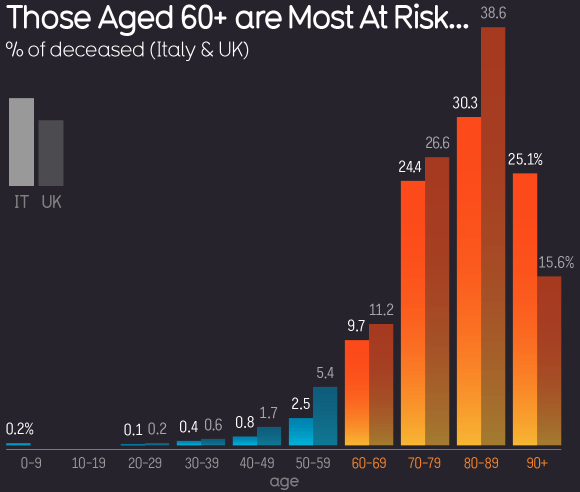

Review my Covid-19 post – I was fully on board with coerced cloistering to prevent a pandemic with what could have been a broad mortality rate. Absent reliable data, that was the logical response: stop the spread. But the evolution of my perspective is dictated by data which clearly shows Covid-19 isn’t a broadly distributed risk – it is highly concentrated to a population that is ready for palliative care.

And if you need to assuage your easily-offended liberal conscience, then pile on to the BLM narrative and recognize that continued confinement will be most devastating to low income families. Disproportionately low-wage earners are in higher-risk jobs, have no savings, and both parents must work. So what happens to all those unsupervised kids who cannot attend school? The earnings and education gap is decried as institutionalized racism, so now it gets exacerbated by these Nanny State policies?

Covid has been politicized to the exclusion of an honest discussion of the social and economic costs. But perhaps I’m too much a libertarian confused by Enlightenment logic and utilitarian theory. I fume in impotent rage. I don’t agree with how they come to their conclusion, but I’m about to join with the gun-wielding, anti-vaccination nut jobs who see a grand conspiracy at play.

__________

Of course there is always the enlightened perspective of the great Cthulhu

He is the universal panacea against institutionalized, structural individualism. He is voracious.

Update 7/13/2020

The pesky unpredictability of the mortality is problematic. Those Covid-deniers are providing an experimental set that shows that there will always be a segment of the younger population at risk: “Man, 30, Dies After Attending a Covid-Party.”

____________

[1] Mark Manson wisely considers Who Wants to Live Forever? in Mind F*ck Monday #48 (copied in full below with original links). That phrase for me conjures a scene from Highlander (1986)

|

| Who wants to live forever? |

| Welcome to another Mindf*ck Monday, the only weekly newsletter that’s even cooler than it sounds. Each week, I send you three potentially life-changing ideas to help you be a slightly less awful human being. This week, we’re talking about topics that are a matter of life and death. No seriously, we’re talking about life and death this week: 1) the scientific progress in “treating” aging, 2) what a vastly longer lifespan would mean for culture and society, and 3) why do things die in the first place? Let’s get into it. (Note: If you enjoy this email, please consider forwarding it to someone who would get a lot out of it. If you were forwarded this email, you can sign up to receive it each Monday morning. It’s free.) 1. Can aging be reversed? – One of the more quietly controversial and interesting areas of scientific progress today is around the idea that biological aging can be treated as a disease and potentially be reversed. For years, researchers have been pioneering methods to limit cellular deterioration, stave off chronic diseases, and help older individuals stay healthy and independent as life expectancies rise. Last week, a new study found that a cocktail of drugs not only slowed biological aging (measured by markers on the individual’s genome), it reversed it by approximately 2.5 years. To my knowledge, this is the first time an aging reversal has been shown in human subjects. This is a stunning result that even the researchers did not expect. (Note: it was a small study and had no control group, so don’t wet your panties just yet. As always, more studies need to be done.) As with most bleeding-edge technologies, the idea that we can defeat aging, like most controversial ideas, has inspired reactions from experts that range from utopian to apocalyptic. I was first exposed to the idea that aging could potentially be conquered by science in Ray Kurzweil’s book The Singularity is Near. In it, Kurzweil’s’ views are beyond utopian. They’re like the religious rapture. In the book, Kurzweil makes the argument that not only will we cure death, but it will likely happen in most of our lifetimes. Kurzweil points out that over human history, not only has life expectancy been increasing, but the rate at which it increases has been increasing as well. So, maybe centuries ago, life expectancy increased at a rate of 0.01 years per year. Then, it increased to 0.1 per year. Then 0.2 per year. Then 0.3 per year. He argues that eventually, life expectancy will hit a tipping point where it increases by at least one year per year, meaning that for every year that goes by, humans are expected to live at least one year longer. Ergo, we all become immortal. The end. Maybe Kurzweil hasn’t spent much time investing in financial markets, otherwise, he’d be aware of the ubiquitous warning that accompanies every exciting chart: “Warning: Past performance is no guarantee of future results.” Indeed, there seems to be a “low-hanging fruit” effect on human longevity. It turns out that giving most of the world running water, sewage treatment, and, you know, food, vastly increases lifespan. So that “exponential curve” of increasing life expectancy that forever increases into the future is more likely an “S-curve” where life expectancy jumps massively as countries industrialize and modernize and then begin to level off at around 75-80 years old. But regardless of the murky science and controversial implications, the lure of immortality is too strong for many to ignore. Companies have emerged that offer to cryogenically freeze your body when you die, promising to keep you frozen until the technology to “cure death” emerges in the future. No, I’m not making this shit up. Apparently, some notable people such as Larry King and Peter Thiel have signed up for it. But don’t get too excited. Freezing your body indefinitely after death starts at around $200,000 USD. Better start saving today! 2. Who wants to live forever? – In my book, Everything is F*cked: A Book About Hope, I argued that one of the dangers of consumer culture is that we often equate “giving people what they want” with progress. Given that we so often want things that are terrible for ourselves (not to mention others), I point out that this is a pretty flimsy standard for measuring the social good. To me, curing aging (and maybe even death) is the ultimate question of, “Okay, we definitely want it… but should we?” It’s hard to imagine the social and psychological repercussions of a population where the average life expectancy is, say, 250 years old. Would we overpopulate the planet? When would the retirement age be? Would our healthcare systems collapse? Would bridge and bingo become Olympic sports? I joke, but I do think there are some serious philosophical questions here. Our ability to value things is driven by scarcity. We often care about things in our lives because we have an abiding sense that we will never experience them again. If we live forever, all experience becomes abundant, therefore much of it loses its meaning. Everything becomes more superficial—there’s no sense of legacy, no sense of, “I lived for that.“ Or what about family? Will it become standard for everyone to have half a dozen marriages and a dozen kids? Will people have brothers and sisters 70 years younger or older than themselves? Will we appreciate our parents more or less knowing that we’re stuck with them for another two centuries and will end up sharing them with dozens of other people? The perceived costs of things like traffic accidents, disease, and war would become much larger. Far fewer people would want to risk getting shot or dying in a car accident if they know they’re giving up hundreds of years of life. People would oddly become much more risk-averse. Pandemics would be waaaay scarier. The power of compound interest would become far more valuable, creating much more of a culture around saving and learning rather than spending and doing. Expertise would reach a point where people spend 30 or 40 years getting educated before starting their careers. Forty really would be the new twenty! 3. The evolutionary value of death – You might read all this and throw your hands up in the air and shout, “What are they doing? This isn’t natural!” But you’d be wrong. Although they are rare, there are “immortal” species on the planet (in this case, “immortal” means that they do not biologically age.) The jellyfish Turritopsis dohrnii doesn’t die. Neither does the bristlecone pine tree. Many species of lobster technically don’t age and could theoretically live forever, the problem is that they outgrow their shells which then decay and fall apart, leaving them vulnerable to predators (talk about tragic). Lifespans vary widely across the natural world. Some sharks and tortoises live for half a millennia. There are species of apes that only live to be about 15 years old. There are several species of flies that live for 24 hours or less. It turns out that death is not inevitable. In fact, death exists for a specific evolutionary purpose. Ideally, by mixing and matching genetics, a species becomes more robustly adapted to its environment. The quicker individual creatures die, the faster they must procreate new generations, and the faster the rate of genetic mutation and adaptation within the species. Therefore, each species has a “sweet spot” for lifespan based on the necessary evolutionary adaptation to its environment. If a species needs to adapt quickly and often, it dies quickly and often. If it needs to adapt slowly (or never), then it dies slowly (or never). That “sweet spot” for humans seems to be every 2-3 generations, or every 80-100 years. The telomeres on our chromosomes appear to “run out” soon after that, effectively putting a limit on how long we can live naturally. This sweet spot probably exists because it’s short enough to stay ahead of the quickly mutating infectious diseases that threaten us, but long enough to have some grandparents around to help raise kids (for more on this idea, see Matt Ridley’s excellent book, The Red Queen). A lot has been said about the scientific potential to alter our own species—genetic engineering, nanotechnology, artificial intelligence, etc. But perhaps nothing would be so fundamental as altering our ability to age and die. Our psychology, our biology, and our societies seem to be largely based on it. Changing it could change everything. The question is, will we be around to see it? Until next week, Mark |