Although I would not call myself a science-fiction aficionado, two of my favorite authors are Frank Herbert and Gene Wolfe.

Two days after my father died, Wolfe followed (April 14, 2019), two lights dimming together, oddly twinned in my memory.

Wolfe’s obituaries appeared in the Washington Post, The New Republic, and The New Yorker.

Wolfe’s The Book of the New Sun (1980-1983, 1987) comprises The Shadow of the Torturer, The Claw of the Conciliator, The Sword of the Lictor, The Citadel of the Autarch, and The Urth of the New Sun. Set in the far future when the Sun itself is dying, it is on the surface a bewildering chronicle of an exiled torturer. He has been rightly called “the Modern Melville” for his narrative density, theological depth, and intertextual brilliance.

As may be evident from some of the footnotes in these posts, I like to find connections among disparate sources. Recently I read an article in Nature that reminded me of Wolfe. That article reported on a paper published in 2011, entitled “Observation of the Dynamical Casimir Effect in a Superconducting Circuit.” Its abstract distilled a revelation:

One of the most surprising predictions of modern quantum theory is that the vacuum of space is not empty. In fact, quantum theory predicts that it teems with virtual particles flitting in and out of existence. While initially a curiosity, it was quickly realized that these vacuum fluctuations had measurable consequences, for instance producing the Lamb shift of atomic spectra and modifying the magnetic moment for the electron. This type of renormalization due to vacuum fluctuations is now central to our understanding of nature. However, these effects provide indirect evidence for the existence of vacuum fluctuations. From early on, it was discussed if it might instead be possible to more directly observe the virtual particles that compose the quantum vacuum. 40 years ago, Moore suggested that a mirror undergoing relativistic motion could convert virtual photons into directly observable real photons. This effect was later named the dynamical Casimir effect (DCE). Using a superconducting circuit, we have observed the DCE for the first time.

The existence of these particles is so fleeting that they are often described as virtual, yet they can have tangible effects. For example, if two mirrors are placed extremely close together, the kinds of virtual photons that can exist between them can be limited. The limit means that more virtual photons exist outside the mirrors than between them, creating a force that pushes the plates together. This ‘Casimir force’ is strong enough at short distances for scientists to physically measure it.

The ancients called mirror-divination catoptromancy (Gk. κάτοπτρον, katoptron, “mirror,” and μαντεία, manteia, “divination”). [The Forgotten History of Mirrors] Wolfe re-enchants that forgotten science with physics.

In Chapter 20 of The Shadow of the Torturer, “Father Inire’s Mirrors,” Severian recalls Thecla’s story of her friend Domnina visiting the court magician after witnessing something impossible in glass.

She realized when she see saw them that the wall of the octagonal enclosure through which she passed faced another mirror. In fact, all the others were mirrors. The light of the blue-white lamp was caught by them all and reflected from one to another as boys might pass silver balls, interlacing and intertwining in an interminable dance. In the center, the fish flickered to and fro, a thing formed, it seemed, by the convergence of the light.

The interposed mirrors conjure being from absence. Whether or not Wolfe knew of the 1947 Casimir proposal, Father Inire’s experiment parallels the DCE precisely; light summoned from the void parallels Inire’s summoning a ‘fish’ with his mirrors. The passage continues:

‘Here you see him,’ Father Inire said. “The ancients, who knew this process at least as well as we and perhaps better, considered the Fish the least important and the most common of the inhabitants of specula. With their false belief that the creatures they summoned were ever present in the depths of the glass, we need not concern ourselves. In time, they turned to a more serious question: By what means may travel be effected when the point of departure is at an astronomical distance from the place of arrival?”

Father Inire dismisses summoning a denizen of the mirror as less interesting than the more serious question of achieving faster than light travel. Respecting that nothing can achieve speeds greater than light, Father Inire explains to Domnia that, with concentrated light and optically exact mirrors, “the orientation of the wave fronts is the same because the image is the same. Since nothing can exceed the speed of light in our universe, the accelerated light leaves it and enters another. When it slows down, it reenters ours, naturally at another place.” So, the mirrors effect time dilation or perhaps fold space (like Guild Navigators in the Dune saga).

Because the characters in Wolfe’s epic do not have equal familiarity with technology, the words they use to describe space travel are archaic metaphors – emphasizing the rareness of exposure and the knowledge deficit.

One space sailor that Severian meets, Hethor, describes his ship being:

Sometimes driven aground by the photon storms, by the swirling of the galaxies, clockwise and counterclockwise, ticking with light down the dark sea-corridors lined with our silver sails, our demon-haunted mirror sails…

For Wolfe, technology is a fallen form of miracle, a material echo of divine power misunderstood by men. The mirror-sails that catch light are both engines and icons: they suggest a world where even propulsion depends upon reflection. This is the theology of incarnation: grace moving through matter.

More prosaically, the “mirror sails” recall Clarke’s Sunjammer (1972) and NASA’s 2011 solar-sail tests, but their demon-haunted quality implies risk of summoning. Hethor’s imagery of ticking, spiraling light hints at time dilation and the constant c: corridors of light itself. We learn that these ships (or is there only one?) travel faster than relativistic corridors.

Wolfe doubles the mirror’s function: transport and drive, invocation and motion. Even as Autarch, Severian never masters their nature. Proof that miracle is merely misunderstood engineering.

Beneath the machinery of time travel and the fading Sun [2] lies Wolfe’s Catholic architecture. Severian’s arc parallels the Passion: he is both torturer and victim, executioner and Christ. His memory, fallible yet absolute, functions as conscience made flesh. Expelled from the guild, he descends through suffering, claims the relic of the Claw (a symbol of grace), and finally dies and returns as the New Sun, the Conciliator who renews the world.

In Catholic eschatology, the Second Coming is both judgment and restoration; Wolfe renders it astrophysical. The dying star is creation under original sin; Severian’s resurrection as the New Sun is the redemption of the cosmos itself.

That duality, cruelty redeemed through compassion, reflects Wolfe’s conviction that salvation operates through the fallen. Grace is mediated by imperfection. The torturer becomes the savior because no one else understands pain so well.

___________________

Other textual connections to explore: When first introduced, Tzadkiel is an animal-like apports, evolves to a caveman, then a normal sailor, to a god-like Adonis figure, a giant angel (first male, then female) and as a tiny tinker-bell sized fairy, but Tzadkiel’s true form is likely a star. This alludes to Frank Herbert’s Whipping Star (1970).

___________________

The cloak worn by the Guild: Fuligin and vantablack.

Fuliginous derives from “fuligo,” the Latin word for “soot.” English speakers have been using the sooty connotation since the early 1620s to describe dense fogs, malevolent clouds, and overworked chimney sweeps. “Fuliginous” can also be used to refer to something dark or dusky. In an early sense (now obsolete), “fuliginous” was used to describe noxious bodily vapors thought to be produced by organic processes.

___________________

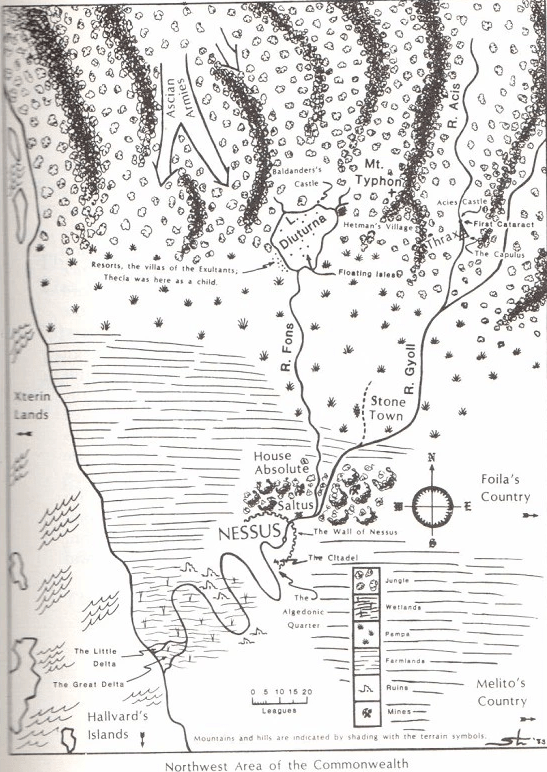

Wolfe shows the long history of human inhabitation of Urth in numerous and subtle ways – the city of Nessus has migrated along the Gyoll and people scour the abandoned sections for artifacts, mines are cities buried where metal is reclaimed and repurposed, Serverian’s tower is an abandoned rocket. Given the span of time this is only logical. Even now anthropogenic mass exceeds that of all life on Earth.

The immense volume of human-made materials is inescapable in Severian’s Urth because it has been continuously inhabited. A related paper (The Silurian Hypothesis) examines whether it would be possible to detect an industrial civilization in the geological record if that civilization had not persisted:

If an industrial civilization had existed on Earth many millions of years prior to our own era, what traces would it have left and would they be detectable today? We summarize the likely geological fingerprint of the Anthropocene, and demonstrate that while clear, it will not differ greatly in many respects from other known events in the geological record. We then propose tests that could plausibly distinguish an industrial cause from an otherwise naturally occurring climate event.

The inverse of Wolfe’s forward postulating – the Silurian Hypothesis considers the potential that humanity was not the first intelligent species – inspiration for early-Earth sci-fi settings.

___________________

[1] Casimir effect also mentioned >here< in the potential for warp drives.

[2] Severian’s Urth has a terraformed Moon so it is green and larger in the sky because it is closer. The sun is red-hued as it burns the last of its hydrogen. The continents have also continued to drift (but probably not enough given the implied millions of years).

Gene Wolfe provides clues to how far in the future Urth is from us, but never to a level of precision.

Modern stellar physics paints a very different future from Wolfe’s dim red sky. The Sun, a main-sequence G-type star about 4.6 billion years old, is still in its stable hydrogen-burning phase. As it converts hydrogen to helium, the core contracts slightly, raising pressure and temperature, which in turn increases luminosity, about 10 percent every billion years.

In one billion years, that extra heat will trigger a runaway greenhouse effect: oceans will boil, the atmosphere will collapse, and the biosphere will end in blinding light, not twilight. Roughly five billion years from now the Sun will expand into a red giant, swelling hundreds of times its current size and engulfing Mercury and Venus, possibly Earth itself. After that convulsion, it will shed its outer layers to form a planetary nebula and contract into a white dwarf, hot but dim, cooling for trillions of years.

The cosmology is clear: Earth dies by fire long before the Sun fades. Entropy in the stellar sense ends in glare, not darkness. Any world orbiting the Sun in its final age would be scorched, not frozen.

Wolfe knew this. By the early 1980s stellar evolution was textbook knowledge. His choice to imagine a cooling, crimson Sun was deliberate: a symbolic inversion, not scientific ignorance.

He draws instead from H. G. Wells’s “The Time Machine” (1895), whose final pages show the traveler on a frozen shore beneath a blood-red, dying star. Wells wrote before nuclear fusion was understood; he conceived the universe as running down into heat-death and cold. Wolfe retains that outdated image because it harmonizes with his deeper theme of Augustinian decline. In The City of God, Augustine describes the fallen world as light dimming into shadow, awaiting renewal. Wolfe re-casts that theology in cosmological form: the Sun itself is fallen, and its rebirth as the New Sun becomes a literal apocalypse.

If one insists on physical coherence, the text still allows a speculative loophole. A civilization capable of planetary terraforming and interstellar mirrors could, in principle, alter its star’s evolution: siphoning hydrogen for fusion fuel, surrounding it with vast collectors, or dimming its output through Dyson-scale engineering. Such manipulation could extend a star’s lifespan at the cost of luminosity, leaving a system bathed in weak red light; stars visible by day, atmosphere thinned and iron-dust tinted. Urth’s red spectrum and day-visible stars would then mark a technologically-induced senescence, not natural decay.

Wolfe begins where astrophysics ends. He accepts the scientific death of worlds, then reverses it to dramatize the moral death of man. The New Sun promises not a correction of physics but the restoration of grace. The universe, in Wolfe’s telling, obeys thermodynamics only until it remembers God.

___________________

Audiobook links

___________________

2 thoughts on “Gene Wolfe”