Arrakis teaches the attitude of the knife—chopping off what’s incomplete and saying: ‘Now, it’s complete because it’s ended here.’

Dune, Collected Sayings of Maud’Dib by the Princess Irulan

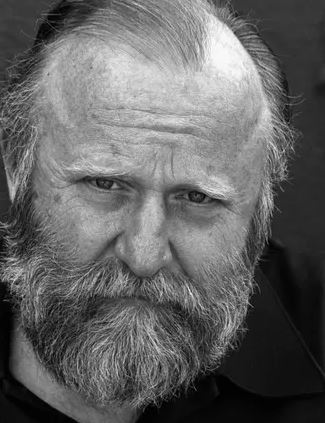

I first read most of the Dune saga in high school and arrived at college in Oregon eager, naïvely, to meet its author. A classmate from the Pacific Northwest laughed and told me Herbert had died earlier that year (February 11, 1986). The desert already had reclaimed its prophet.

___________________

The seed of Dune sprouted in Florence, Oregon, where the U.S. Forest Service was experimenting with sand stabilization to keep dunes from swallowing the highway. Herbert became fascinated by the physics of moving sand (fluid dynamics) and wondered: what if an entire planet behaved that way? From this question flowed another realization: most religions arise in the desert. Out of that terrain Herbert layered ecology, anthropology, and theology to produce an epic: man shaping his world and the world reshaping him. “Ecology,” he said, “is the science of understanding consequences.”

The political architecture of Dune is explicitly feudal; a recognition that human societies, left to themselves, crystallize into hierarchy. Herbert used that archaic clarity to expose the mechanics of power. He distrusted centralized authority and viewed bureaucracy as entropy in political form.

I wrote the Dune Saga because I had this idea that charismatic leaders ought to come with the warning label ‘May Be Dangerous To Your Health’

JFK was on his mind; Paul Atreides became the example. The hero’s arc was itself the warning label.

The religious and psychedelic threads (prescient vision, ancestral memory, the trance logic of prophecy) were likely deepened by Herbert’s experiments with peyote and his 1960 friendship with Alan Watts. These encounters widened Dune’s exploration of time and identity, of consciousness folded into matter. The Zen-Sunni syncretism and the Orange Catholic Bible anchor Paul’s metamorphosis from noble to messiah. In gaining mythic vision he forfeits individuality, dissolving into the Jungian collective he embodies.

The Fremen form Dune’s moral axis; a persecuted people who remain resolutely stoic, adaptive, ecological. Paul joins them and is remade as Muad’Dib. The parallels are deliberate: T. E. Lawrence, leading his men to Aqaba on one horizon, the Islamic Mahdi on another. Their prophecy promises a leader who will “guide us into paradise.” Paul fulfills it, reclaims his title, ascends the throne, and begins to green the desert. Yet in Herbert’s geometry, every paradise conceals its own fall; the seed of jihad germinates in the first oasis.

Herbert had originally conceived Dune and Dune Messiah as a single novel showing Paul’s ascent and fall entwined. Only at his editor’s insistence was it divided for length. Thus Dune ends at the false summit of triumph, where the myth still shines. “The difference between a hero and an anti-hero,” Herbert observed, “is where you stop the story.” Messiah resumes the line and bends it downward. Paul abandons, in fear, his prophetic visions. The Jihad has shattered feudal limits: humanity expands explosively, but at an immense cost of life.

Herbert deliberately ended Dune at the point of Paul’s apotheosis. As Herbert said, “The difference between a hero and an anti-hero is where you stop the story.” That distinction becomes explicit in Dune Messiah, where Paul abandons, in fear, his prophetic visions. The Jihad has shattered feudal limits: humanity expands explosively, but at an immense cost of life.

Paul’s son Leto II inherits the burden and conceives the Golden Path: a forced evolution to prevent extinction. He sees that humanity, if left within its feudal terrarium, will suffocate. Merging with sandtrout, he becomes the God Emperor: half human, half worm, wholly necessary because it was the only means to extend his life, to become the God Emperor, and force humanity down the path.

Ever the ecologist, Herbert warns us against humanity becoming a monoculture. As large as it was, the known universe could be controlled by a single interest (the spice) and single will (the God Emperor). Such a structure is vulnerable. Leto’s rule is purposefully oppressive to “teach humanity a lesson that they will remember in their bones.”

What is that lesson?

That safety breeds extinction. Sheltered safety inextricably culminates in species stagnation and death. To inoculate the species, Leto restricts spice, limits travel, and engineers pressure to force rebellion, dispersal, and the evolution of minds opaque to prescience.

Herbert understood that humanity needs conflict and volatility to flourish. He knew that peace, pursued too perfectly, becomes a trap. Leto’s tyranny drives humanity outward, guaranteeing survival through diversity.

Herbert treated evolution not as backdrop but as engine. The Fremen and Sardaukar are early proofs: harsh worlds forge superior stock. Under Leto’s empire, breeding replaces battle as selection pressure. By Chapterhouse, even the average human runs marathons; the exceptional dodge las-fire. The Bene Gesserit’s ancestral recall and the Honored Matres’ synaptic ferocity are refinements of the same law; environment sculpting potential.

Heretics of Dune shows that the Golden Path succeeded. Prescience no longer governs destiny; human will is free again. The newly arrived Honored Matres return from the Scattering with lethal skills but flee an unnamed, greater threat.

By Chapterhouse: Dune, survival seems assured, though danger remains diffuse. The species endures precisely because control is gone and human potential is unlimited.[1]

________________

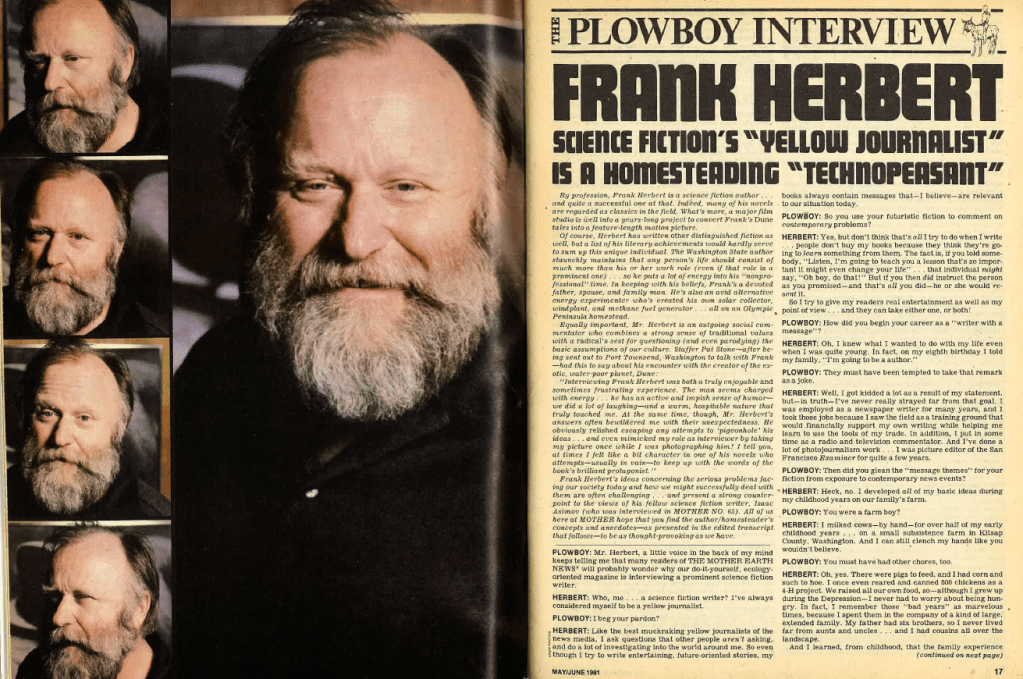

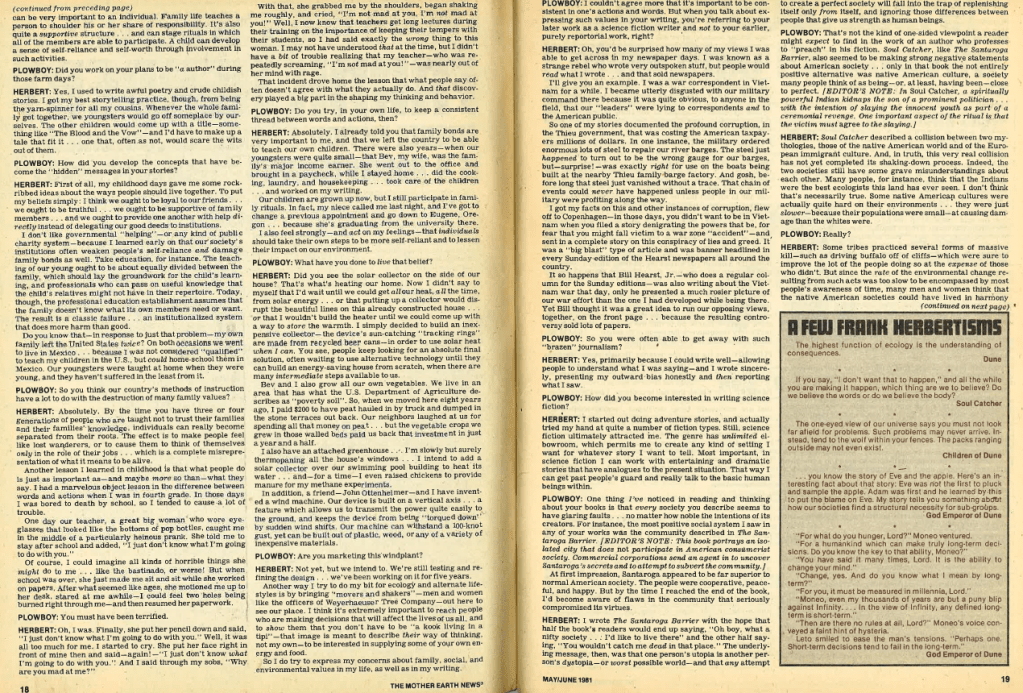

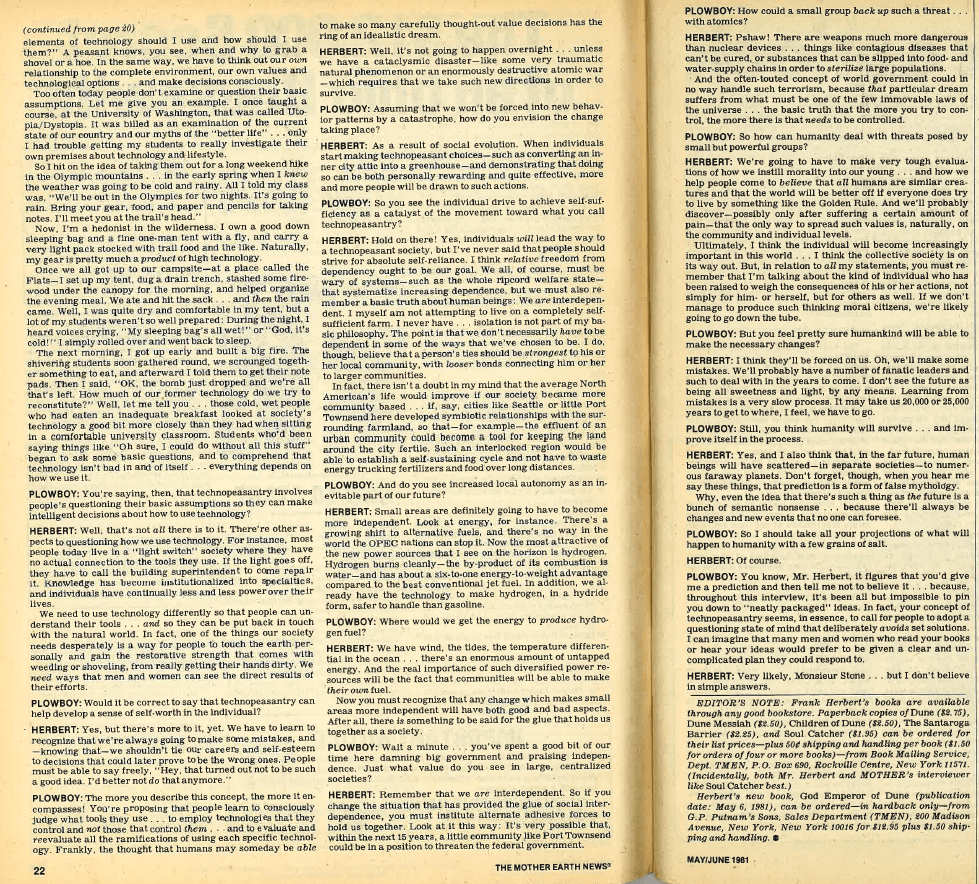

Below are images from Mother Earth News, #69, May/June 1981 – an interview with Frank Herbert.

>This< recent paper on cellular learning is an intriguing potential – some basis for the idea of gholas and genetic memories? Can single cells learn?

________________

[1] I do not consider anything written by Frank Herbert’s son as canonical. I have read only the first few chapters on one of the all-too-numerous additions. Unfortunately his son is not the writer his father was.

4 thoughts on “Frank Herbert”