I have just finished Victor Hanson’s The Western Way of War (1989). It provides a visceral depiction of what it was like to be a hoplite. It is a very unromantic portrayal that emphasizes the communal aspects of ancient warfare; the necessity of group action where doing your role in the phalanx was far more important than individual achievement and warriorship. Success in hoplite warfare did not require martial excellence, just discipline, endurance and thumos.

The individual heroics of the Illiad did not win battles. The power of the phalanx was its ordered charge into the opposing ranks to force a rout. Hanson’s depiction shows the power of heavy shock troops. Scattered throughout these posts are references to ancient warfare, and usually to the ancient Greeks, because there are always valuable lessons to learn from history.

Hanson’s argument is well-constructed and academic and perhaps tedious for a casual read, but his concluding Epilogue is an important refutation of any heroic interpretation of ancient Greek warfare: “…donning the panoply and marching out only called to mind a time for killing and dying in the nightmarish world of the phalanx; it did not invoke any mystique of ‘the cult of the warrior'” (1989:221). There was a resolute fatalism on the clash of spear on shield and best be done with it quickly and efficiently. The mettle of these ancients and what they could endure is understated in the secondary sources.

In Dracula as Historian – I mused on the differences between us moderns who exercise to maintain health and physique and the ancients for whom physical exertion was daily life. Those ancients had more grit than we do – simply because it was a requirement to live: they walked to get anywhere and over uneven terrain; they had limited tools for mechanical advantage. Even kings plowed their own fields: Odysseus’ sanity was questioned not because he was tilling but because he sowed the fields with salt.

Toil was the norm, rest a luxury. Thus, while the overall physical size and life expectancy is demonstrably less than the modern average, I contend that their raw physical endurance, tenacity and grit was exponentially greater.

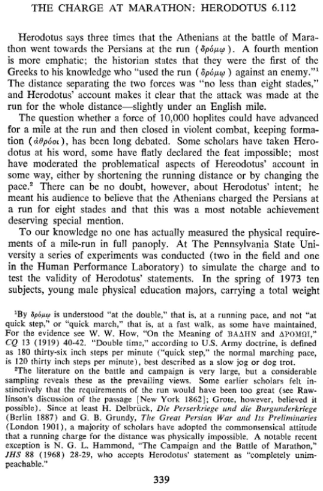

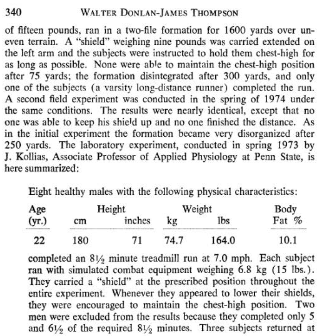

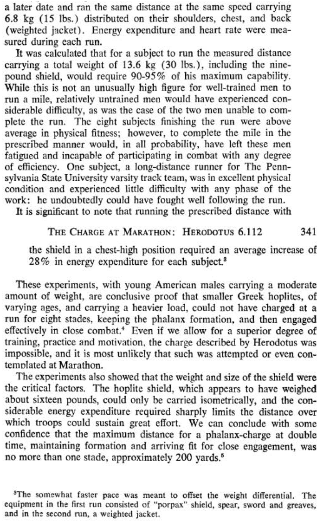

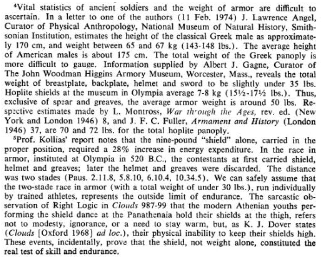

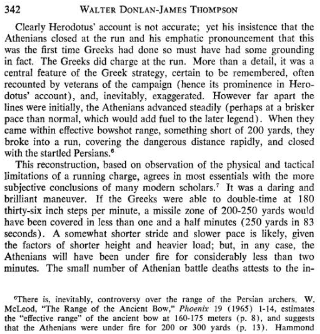

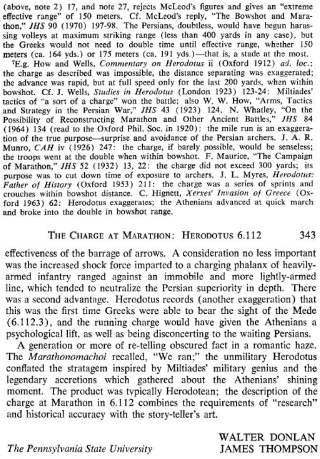

Hanson provided the reference to the “test” I remembered imprecisely in the earlier post that was conducted using modern (1973) college students who tried to replicate the Athenian charge at Marathon against the Persian invaders. The full article is reproduced below, but the poignant error is to assume that physical education students are meaningfully comparable with Athenians of 490 BC.

My personal experience as a high-school decathelete is that physical fitness, as we now define it, is a poor substitute for the rigors of working a farm – even one with all the advantages of modern mechanization. Bucking hay to get it off the field and stacked in the barn before the rain, splitting and stacking cords of wood, hauling water to the feed troughs, corralling pigs, all the routine “chores” are physically exhausting. Put simply, the work is demanding and it is endless even as it changes with the seasons. Plowing, sowing, reaping, harvesting, slaughter, the tasks differ, but work is constant. On the occasional summer, I helped for extra cash and was easily out-worked by the stalwart farm hands who toiled day-in day-out, even though I knew I was more “fit” than they.

So, to compare a Penn State phys-ed student to a weathered Athenian citizen-solider is a mistake. A better comparison would be to an Army Ranger, a cohort more inured to the required rigors and with conditioned fortitude similar to our average Athenian. Rangers deploy with gear weighing as much as and almost as awkward as a hoplite panoply. But all the specialized conditioning and forced deprivation required to prepare Rangers would be nothing unusual for an Ancient Greek. What we construe as grueling hardship would have been just another day for them.[2]

Hanson cites Donlan and Thompson as an authority in a few locations (specifically 1989: 56, 144) and makes a short corroborating observation, “My own students at California State University, Fresno, who have created metal and wood replicas of ancient Greek and Roman armor and weapons, find it difficult to keep the weight of their shield, greaves, sword, spear, breastplate, helmet and tunic under seventy pounds. After about thirty minutes of dueling in mock battles under the sun of the San Joaquin Valley they are utterly exhausted” (Hanson 1989:56). These are pampered moderns who have not had to do manual labor their entire life under a Mediterranean sun.

That the Donlan and Thompson “study” continues to be cited, especially by an historian as tied to the earth as Victor Hanson (himself a farmer) is surprising. Read the article in full and pay attention to the facile assumptions of physical limits. I am not contending that Herodotus had all the facts correct (he admits he doesn’t) just that Donlan and Thompson underestimate what highly motivated, tough farmers would have been capable of doing.

_______________

________________

Addendum – I suggested an Army Ranger would be a better equivalency to a hoplite – here is a Swiss comparison of a firefighter, soldier, and Medieval knight running an obstacle course. The comparative ages of the participants are different but the gear is relatively similar in weight. This is confirmation that what we moderns construe as elite level physical conditioning was in fact closer to the norm for our forebears (who, it should be noted, were on average younger).

______________

[1] Palamedes placed Telemachus in front of Odysseus’s team to reveal his sanity: crafty Odysseus outwitted and beaten at his own game! Odysseus never forgave Palamedes and took his revenge during the Trojan War when he set him up as a traitor (Hyginus Fabulae, 105). A petty revenge? No, a contest of cunning.

[2] Physical toughness and endurance is demonstrably not the most important factor in determining resiliency. Mental toughness is paramount for overcoming extreme challenges. Great things do not come without a bit of adversity. Nothing amazing happens inside our comfort zones.

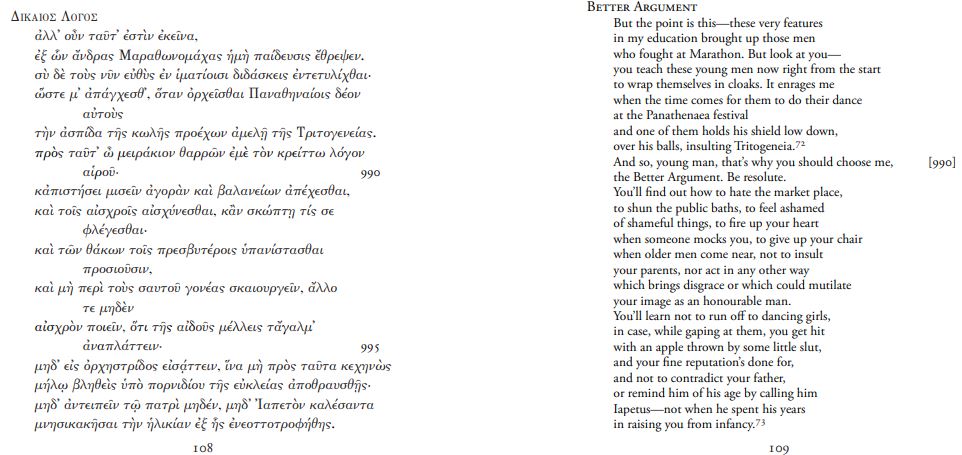

Even in the ancient sources, the veterans decried the “softening” of Athenian youth who could not hold up their shields as they dance at the Panathenaea (Aristophanes, The Clouds).

Translations of this scene appear to have “Better Argument” mocking the youth of Athens for their modesty (hiding their balls with their shields) but contemporaries would correctly understand this as a rebuke for them to grow bigger balls; to be manly enough to hold their shield high where it protects against the crash of spears and – most importantly – offers refuge to the man his left fighting in close proximity.

The need to hold the shield high is also captured in the movie 300 where Leonidas rejects Ephialtes because he cannot raise his shield.

Despite this quibble over a secondary source, I contend that Victor Hanson is the finest contemporary historian on warfare. He understands the unfortunate reality that conflict is part of the human condition. His is a realistic rather than aspirational view of human nature.

The academic challenge to Hanson’s Western Way of War is rationalized by the relatively short duration that the heavy infantry are the primary means of battle.

Virtūs et Honos

3 thoughts on “HOPLITES and PHYSICAL LIMITATIONS”