Beyond questioning, The Princess Bride (1987) is one of the greatest movies of all time. (The book, by William Goldman is wonderfully cynical, so do not neglect reading it.)

And without a doubt, one of the best rapier duels is set on the Cliffs of Insanity between Westley (played by Cary Elwes [1]) and Inigo Montoya[2] (played by Mandy Patinkin).

The cinematic presentation is energetic, with dexterous swordplay, great banter, and a bit of acrobatics for campy effect fitting the tone of the movie. The book’s presentation is more succinct:

They touched swords, and the man in black immediately began the Agrippa defense, which Inigo felt was sound, considering the rocky terrain, for the Agrippa kept the feet stationary at first, and made the chances of slipping minimal. Naturally, he countered with Capo Ferro, which surprised the man in black, but he defended well, quickly shifting out of Agrippa and taking the attack himself, using the principles of Thibault.

Inigo had to smile. No one had taken the attack against him in so long, and it was thrilling! He let the man in black advance, let him build up courage, retreating gracefully between some trees, letting his Bonetti defense keep him safe from harm.

I read the book and saw the movie before ever reading Capo Ferro or investigating the references to other fencing masters.

Who was Capo Ferro? Capo Ferro,or Ridolfo Capoferro, was a fencing master from Siena, Tuscany, and his treatise on the use of rapier, Great Representation of the Art and Use of Fencing, was first published in 1610. Capo Ferro based some of his theory on Camillo Agrippa’s work (1553); using the four primary guards Agrippa advocated (as opposed to the eleven guards advocated by Achille Marozzo (1536)). His teachings solidly are in the Italian tradition and in the use of the rapier.

The rapier is a weapon of the point: the thrust is its nature and it is lethal! Rapier techniques were introduced to Britain in the late 1500s and despite the work of stalwart Englishmen like George Silver (who disapproved of continental frippery), the rapier soon became the dominant weapon. In Britain it was often considered a murderer’s weapon because using the point-dominant techniques are an attempt to kill, and not just defend oneself.

Capo Ferro would agree morally but not with the characterization of the weapon: “The aim of fencing is the defense of oneself … for this reason one should know the value and excellence of this discipline … Therefore, it is moreover seen that defense is the principle action of fencing. No one should proceed to offense if not through the route of legitimate defense.”

From this outline of natural rights, Capo Ferro proceeds to outline the requisite developmental progression; reason, nature, art, and exercise. Even in translation, the language is evocative and concise:

There are four primary causes of this discipline: Reason, Nature, Art, and exercise. Reason as the one that disposes nature. Nature as potent virtue. Art as ruler and moderator of nature. Exercise as the minister of the art.

Capo Ferro, Ch.1, 5.

This is a universal statement applicable to all martial arts and deriving from natural law theory. Capo Ferro explicates:

Art rules Nature and with more security, escorts and guides it through the infallible truth and to the true science of our defense by the order of its precepts.

Ch.1, 9.

Our natural urge to rational self-preservation is refined by learning a martial art (and Capo Ferro asserts his is the pinnacle).

Art observes Nature and sees … and it sharpens, polishes, and refines the things of Nature, reducing it little by little, until the peak of its perfection.

Ch.1, 11.

We select from natural tendencies and the innate abilities of our bodies to refine them into a cohesive art. But he is careful to remind us:

Exercise conserves, augments and stabilizes the forces of art, nature, and furthermore the Science. It produces the prudence of many details in us.

Ch.1, 10.

The universal admonishment to practice, practice, practice.

Capo Ferro traces the evolution of his art from a simple club through the Roman era to show the primacy of his system. He considers the ideal length of a weapon to be from the sole of the foot to the underside of the armpit; “All weapons which differ from this distance of natural offense and defense are most bestial, very adverse to nature, and therefore useless to civil conversation.”[3] Thus concludes his introduction to Italian Rapier.

Chapter III

Although he is teaching specifically to the rapier, Capo Ferro defines a sword more generically, more universally: “Therefore, the sword is a weapon of pointed steel and is apt to defend oneself in the distance which one or the other can naturally, with peril to life, offend.” And its “purpose is defense, which firstly means to keep the adversary far away, so that he is not able to offend me.” But failing that, “defend means to offend and to strike. It is the last and helpful remedy of defense.” Capo Ferro knows one cannot rely solely on defense such as: “In the case when the enemy crosses the boundary of the first defense and brings himself close so that I have come into danger of the offence…” Hence the need for the point.

Where Salvator Fabris (1606) divided the sword into four parts, Capo Ferro defines the sword with the two parts modern fencers are most familiar with: the forte and the foible (Capo Ferro uses the archaic debile for the foible.) The forte is the lower, stronger part of the blade (going from the base of the sword to the middle), and the foible is the uppermost part of the blade. The forte is for parrying, and the debile for striking. The edges are defined: the false edge (the back edge of the blade) and the true edge, which was the side of the blade on the same side of the knuckles. (More on the false edge, see cuts below.)

Chapter IV

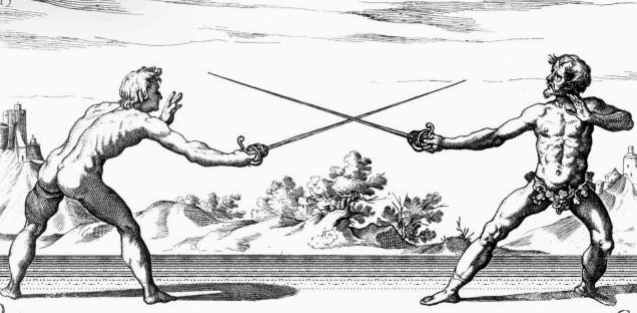

Having familiarized the reader with the weapon, Capo Ferro teaches the importance of distance – the misura:

“The misura is a correct distance from the point of my sword to the body of the adversary from where I can strike him” (Ch.4, 44).

The misura is the measure, the distance, from the point of your sword to your opponent’s body. There are three ranges:

misura stretta (short measure), in which one could hit the opponent by reaching out by only pushing out the body from the legs;

misura larga (long measure), in which one would have to lunge to hit the opponent;

strettissima misura (middle measure), in which one can strike the opponent’s sword or dagger arm from misura larga.

Every art needs consider the ranges of combat.

Chapter V

“In fencing the term tempo comes to mean three diverse things. First it signifies a proper space of motion or stillness.”

Along with measure is time, tempo. Tempo involves both distance and time; it represents the time it takes to perform a movement. One can move in dui tempi (two movements), or primo tempo (in which there is only one movement of the sword). Mezzo tempo is the quick attack, most likely to the hand or arm, and the contra tempo is the counter-attack, the attack one throws as the opponent is in an attack-motion.

Capo Ferro goes into a great deal of detail, showing the connection between measure and tempo. This is the fundamental truth we find in swordplay: the interconnection between time, distance and accuracy. True Times. He stresses the attack in mezzo tempo for short range, while misura longa requires patience (Ch.5, 54).

Primo Tempo – striking with a single move from either the wide or narrow measure.

Dui Tempo – striking with at least two separate moves, such as a beat and a cut, or a parry and a riposte, two distinctly separate actions.

Mezzo Tempo – attacking either of the enemies advanced arms from the wide measure.

Contra Tempo – striking your opponent during his attack, either through a single tempo defense, or another action which allows you to strike with one action during their attack, such as a void. Notice in Italian rapier, it is considered safest to attack during an opponent’s move, whether they change guard, adjust their footing, disengage, or initiate an attack.

Beats and broken rhythm!

Chapters VI, VII, VIII, IX

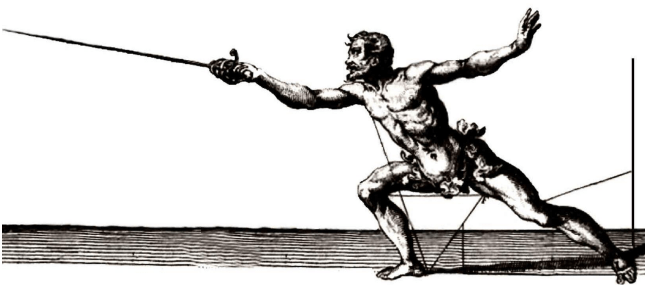

The use of the head “is truly a principal thing … it is necessary that it comes to be placed … where it can act as a sentinel and perceive the landscape from every side.” Perceptual speed. The body placement – the vita – is described in detail, but is recognizably hanmi: “The skew of the body will be such that anyone does not show more than half of the chest…” The arms are an extension of the body, and “In striking, the right arm will be extended in a direct line…” Weapon, hand, body, feet.

Chapter X

The Guards:

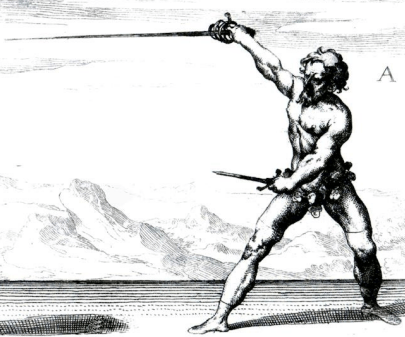

“The guardia is a positioning of the arm and the sword…to keep the adversary far away from every offense and to offend him in case he comes near to harm you” (Ch.10, 97). Like Agrippa, Capo Ferro advocates (primarily) the use of four guards.

Prima (First): The thumb is down, and the palm is to the outside of the body; the true edge faces upwards. It is prima because it is the first position you will be in once drawing the sword from the scabbard and pointing to your opponent. It is very aggressive, is a good defense versus cuts, though it tires the arm and offers no protection to the lower body (hence the dagger).

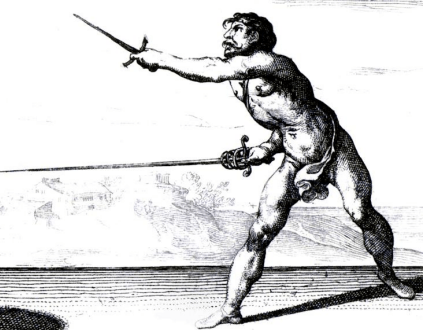

Seconda (Second): The palm is turned down, and the true edge is to the outside. It still protects the upper body.

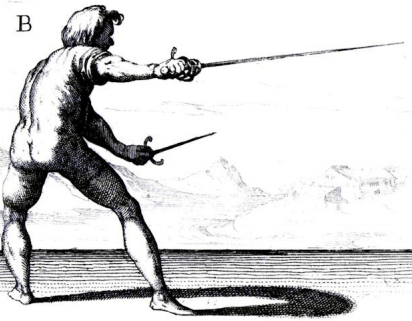

Terza (Third): Knuckles are down, the true edge is down, and the arm is in a more comfortable position. The hand can be turned either way to make effective parries. Capo

Ferro calls this “the only guardia” (Chapter X, Section 98). He claims it ideally protects the body, and and is in ideal position for striking.

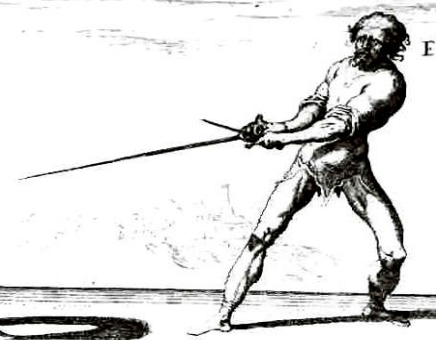

Quarta (Fourth): The palm is up, and the true edge faces inwards. The lunge should be preformed from this position, and attacks from this position are good for attacking both the outside line and the inside line. It reveals too much of the body, though, according to Capo Ferro, and should be used just for attacking and not for protecting your body.

He also presents two additional guards which have limited use:

Qunito (Fifth) – a withdrawn guard used with a dagger

and Sesta (Sixth) a low guard similar to a German longsword.

Guards are the starting position and are discussed in every manual of arms. As a combat strategy, iaijutsu formalizes an attack from a draw – a system that is not well developed in Western arts.

Chapter XI, XII

Seeking the Measure and Striking:

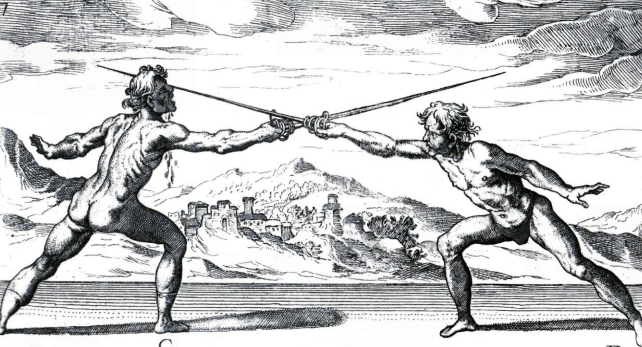

“While I strike, I necessarily parry together with it, in such a way that I strike in a straight line … because when I strike in this manner … the adversary will never strike me … because the forte of my sword travels in a direct line and comes to cover all of my body.” Sounds like Bruce Lee’s straight blast. Capo Ferro elaborates that in comparison to the thrust, “the cut is of little value because I cannot strike by cut … I cannot do the rotation of the arm and the sword without entirely uncovering myself … one cannot demonstrate it better than the point.” The exception to this rule is: “But without a doubt, on a horse it is better to strike by cut than by thrust…”

Capo Ferro then provides Some Advice

- Watch the weapon hand.

- Never parry without a riposte.

- Learn the single sword – it is the foundation. With a single rapier, the sword most be able to both defend and attack: and both are only achieved by gaining blade domination.

- Methods against the brute – first, strike quickly at his leading hands and arms – second, retreat (void) so he “leave him to proceed at emptiness … and then you instantly drive a point into the face or chest.”

- To become a perfect swordsman, it is necessary to train “with diverse practitioners daily … you must always exercise with those who know more than you…”

- The best guard “is with the sword level in a straight line which shall divide the right flank through the middle and the point of it shall always look for the middle of the body of the adversary…” Seigan no kamai.

- Feints are not good because they lose tempo and measure.

- Learn from those who can do what they teach.

Concepts of Attack – Integrating Measure, Time, and the Placement of the Blade:

Capo Ferro describes ways in which one both thrusts and cuts. There are various types of cuts, defined by the direction of the strike. In the same way, there are different types of thrust. The most common, the stocatta, is the thrust that originates in terza, and targets the opponent’s right shoulder. The imbrocatta goes from prima to the opponent’s left shoulder. The punta riverso is made from quarta, with the palm up, to the outside line of the opponent’s shoulder.

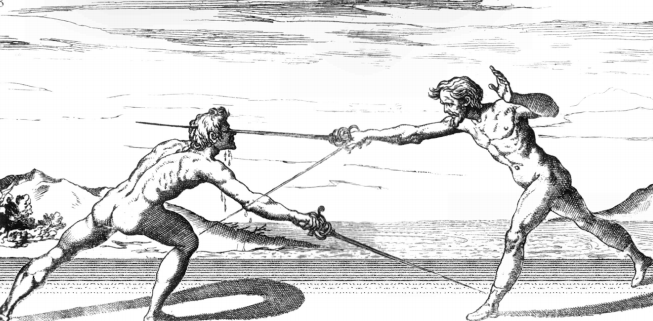

The thrust (lunge) is the primary attack:

The lunge is the defining method of attack in rapier and requires using the extension of the whole body in line to attack. The lunge as defined was likely developed to the level we know it in the middle of the sixteenth century and first presented by Agrippa (1551).

The lunge was a mathematically calculated movement which involves coordinated body mechanics to work correctly. The lunge is by far the fastest way to attack from misura larga (wide measure), and done properly, is a lightning fast movement of the human body.

However, you must not assume it is the only way to attack, nor always the best. Certainly the lunge is the most commonly used manner to attack, but to forget the pass would be a big mistake. The lunge, despite being fast, leaves you in a vulnerable position, and lowers your posture, potentially leading to a weaker position. The pass on the other hand does not leave you in a vulnerable position (when closing to narrow measure), and keeps you upright and in a strong position.

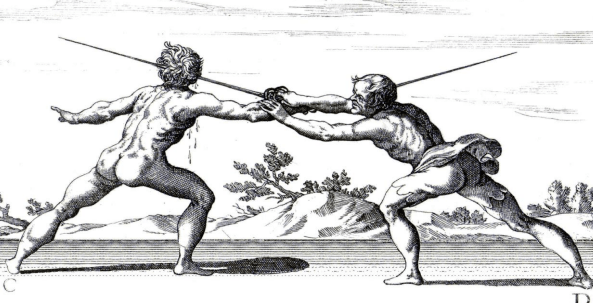

A novel term Capo Ferro introduces is the stringere. The act of stringere is done to gain misura, or to gain the sword, or to “uncover the adversary from the outside and from the inside.” The stringere involves making contact with the opponent’s weapon, in order to guide him to a position in which you can attack in your own measure. Instead of the disengage, Capo Ferro provides the fencer with the cavare. It is not a disengage, because the opponent’s sword does not necessarily have to be engaged to perform a cavare. Executing a cavare involves moving the tip of your weapon, either from above or below the opponent’s tip, and either placing it in line for attack or to gain stringere.

To stringere, is to pre-parry your opponent’s blade, either through direct contact, or simply alignment and no contact. To understand how this is done and why it is useful, you need to understand the principal of the strong and weak part of the blade.

You can stringere your opponent’s blade from any of the primary guards. The purpose is to attain a tactical advantage. By stringere your opponent you effectively pre-parry their blade, allowing you to strike or parry on the line that you have positioned yourself with relative ease and safety. This search for advantage between opponents can therefore result in a cat and mouse game of stringere, disengagements, and counter stringere by each party. Other fights may feature very little obvious stringere accomplished primarily with body and hand angle adjustments without necessarily finding the opponent’s blade.

_________________

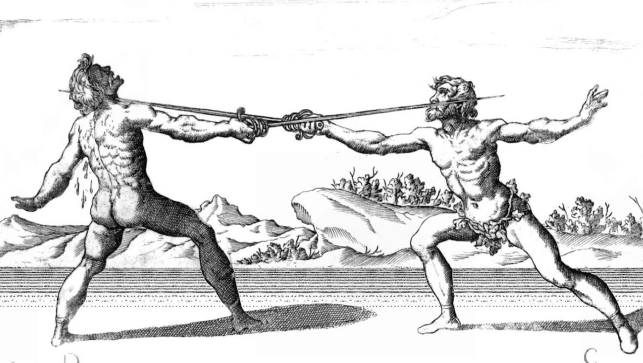

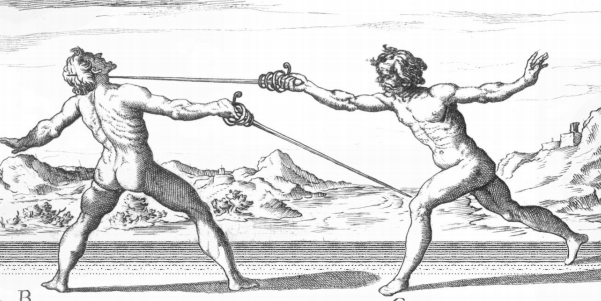

The Single Time Defense

The basic defenses are the same as the basic attacks. A good rule for any martial artist, avoid, ‘dead parries’ where on the defense you simply block the oncoming attack: you cannot win by defending. In combat, that kind of defense is a last resort, because it is a wasted opportunity to strike your opponent.

Therefore, if someone lunges at you in second on the outside line, you displace and strike them in second. If your opponent attacks in fourth on your inside line, you displace and strike them in fourth. (Review the cognates in Punch to the Face.)

It is of note that when making a single time counter, you do not need to move your feet at all, because your opponent has lunged at you, entering into the narrow measure (misura stretta), allowing you to strike from a fixed footing position. However, a good fencer will learn to be quick on the recovery, and a bad fencer may strike short, either scenario can rob you of your strike. Lunging during a single time defense will ensure that you strike your opponent well.

On attacking the legs

Capo Ferro admonishes against strikes to the leg in single rapier combat because they leave you dangerously open to a counter. It is an attack from ‘false’ distance. The ‘true’ distance is the shortest distance to your opponent, being the sword and arm in line and parallel to the ground. If you strike diagonally, you lose much of the reach, and the ‘true’ distance.

How to use Passing Steps

With the katana and many European sword forms, the swordsman proceeds either foot forward and stepping through like walking to change guard and distance, this is not commonly practiced with rapier. With rapier, the left foot is rarely forward until the passing step is used. (There are a few notable exceptions, such as in Spanish fencing, and when using a cloak.) Having the left foot forward reduces the coverage of the sword to the body. It also means that you can no longer lunge, only pass, whereas with the right (lead) foot forward, you can both lunge and pass.

Passing steps are used for specific purposes, never adjusting distance or guards. The defense against a leg attack seen above was one example of when a passing step is used, as it removed the lead leg from danger, while not reducing the reach to strike.

The passing step is also used in a very aggressive manner to close from the wide to the narrow measure. You can pass on both the inside a outside line, though be aware that it requires better timing than the lunge, as the recovery time is slower.

Passing on the outside line

This is best used against an opponent who lunges at you on the outside line. Passing in this situation allows you to step safely past the point of their extended weapon, and allows your offhand to come into play, to either push their blade away to allow a strike, or more commonly, to take hold of their arm or weapon.

Once you have hold of their arm of weapon, you are free to strike them, but be aware, most people first reaction is to try and take hold of your sword. For this reason, once you have hold of their wrist or weapon, a cut is usually better than a thrust, because they have some chance of parrying or grabbing the blade during a thrust, whereas the

best they can do against a cut is put their offhand in the way, which the cut will beat down, allowing another strike to finish them off.

Passing on the Inside line

This move is not at all natural to the human body, as it will require your upper and lower bodies twisting in opposite directions. To use this move, have your opponent wait in third guard on your inside line.

Then you must twist and extend in to fourth, passing the rear foot forwards towards your opponent, while your lead shoulder twists towards the opponent’s sword. When done correctly, this is a very safe and strong strike, however, you need good speed and timing to make it work. This is often used as an attack when your opponent disengages from the outside to inside line:

This technique closely resembles the fleche seen in modern sport fencing.

Cuts

First, never underestimate the usefulness of the cut. Many descriptions of the rapier will suggest that the rapier was incapable of cutting: do not believe them. Just look at the historical rapier treatises and the number of cutting techniques within them to understand the cut was important. While some rapiers have no sharp edge these are the minority. Rapiers were combat effective, and having a cutting edge not only allowed for a greater range of techniques, but also reduced the risk of blade grabs. So understand that the ‘false edge’ is a positional description, not an indication that there is no sharp edge. (Compare with the Bowie, for example on the potential confusion on terminology).

Nevertheless, because a rapier is more thrust orientated, the terminology for cutting is simplified.

Mandritto – a cut which originates from the outside of the body, cutting towards the inside.

Riverso – a cut which originates from the inside of the body, cutting towards the outside.

Fendente – a downwards vertical cut, usually to the head

Falso – a cut with the back/false edge of the blade. These can be further classified as ‘Falso Riverso’ for example, for a false edge cut made from inside to outside.

The cut is that it is not used just to cause damage to your opponent. A cut can be used to strike, to beat an opponent’s blade, to parry, or to cover a line when recovering. Rarely ever strike a cut from the wide measure, because to do so means lifting the sword, and creating an opening for our opponent to strike a thrust.

The rapier as a soldier’s weapon evolved to a civilian small sword, which is covered by Domineco Angelo.

___________

[1] Two years earlier, Carey Elwes, as Josef, challenged Dr. Frankestein (played by Sting) to a duel in The Bride (1985): “Chose your weapon, I am equally skilled in all” – great line when you have the skill to back it up!

[2] Indigo is searching for “The Six-fingered Man” who killed his father. >This< is an intelligent inquiry on polydactyly and points to >this< cursory review of the historical (artistic) record. As an additional aside, how many readers remember that Hannibal Lecter (from Silence of the Lambs) also has six fingers?

[3] The recommended length of the rapier, then, is the same as a jo in Aikido. This is longer than the modern foil, derived from the dress sword, or épée de cour.

__________

The Association for Renaissance Martial Arts has done an amazing job in collecting and researching the methods of past masters >start here<

One thought on “CAPO FERRO – rapier”