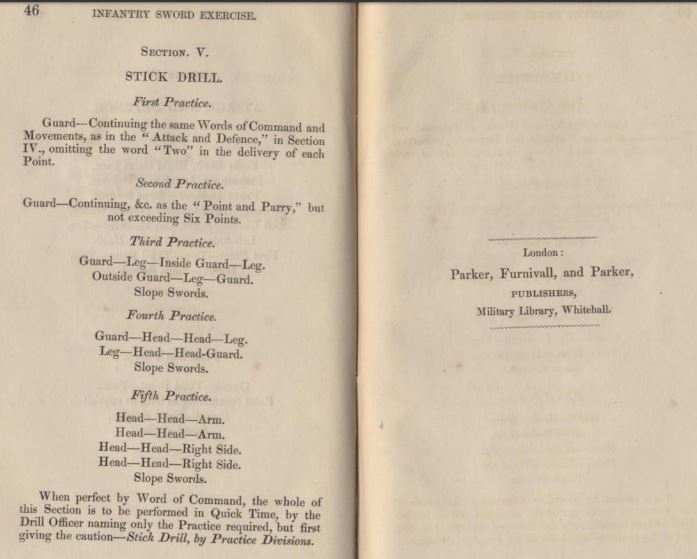

Henry Charles Angelo is the grandson of Domenico Angelo. Henry Charles’ father, Henry Angelo ‘the elder’ (c.1760-1839), took over Domenico’s fencing academy on Carlisle Street, London, in 1785. With the encouragement of the Prince of Wales (future King George IV), Henry Angelo sponsored fencing exhibitions among some of the most famous swordsmen of the day. In 1798 Henry published Hungarian and Highland broadsword (see diagram below). The the naval cutlass and footman’s sabre were gaining ascendancy over the earlier sword forms.

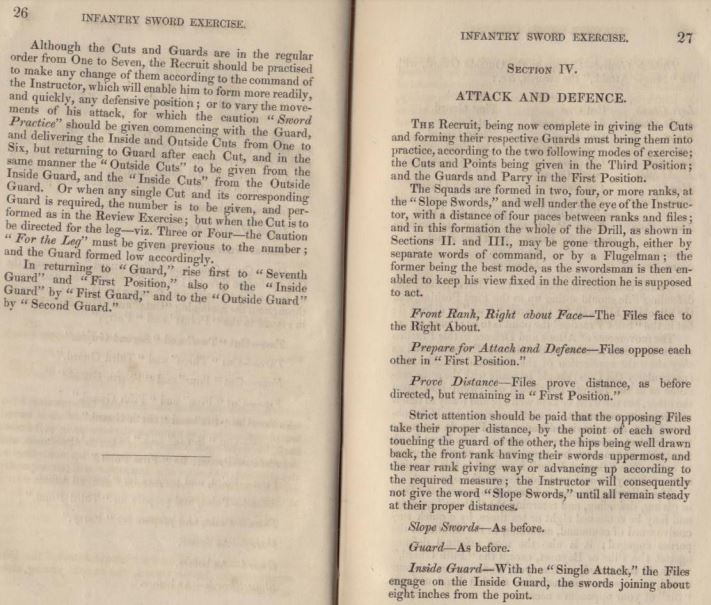

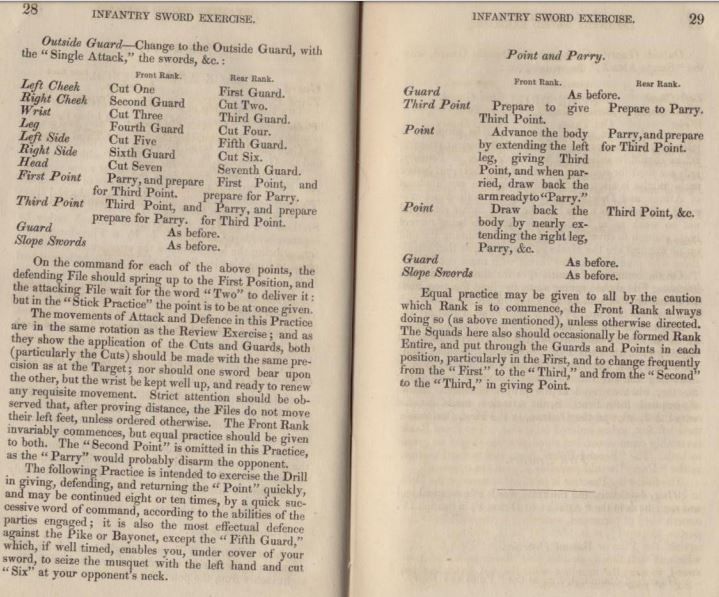

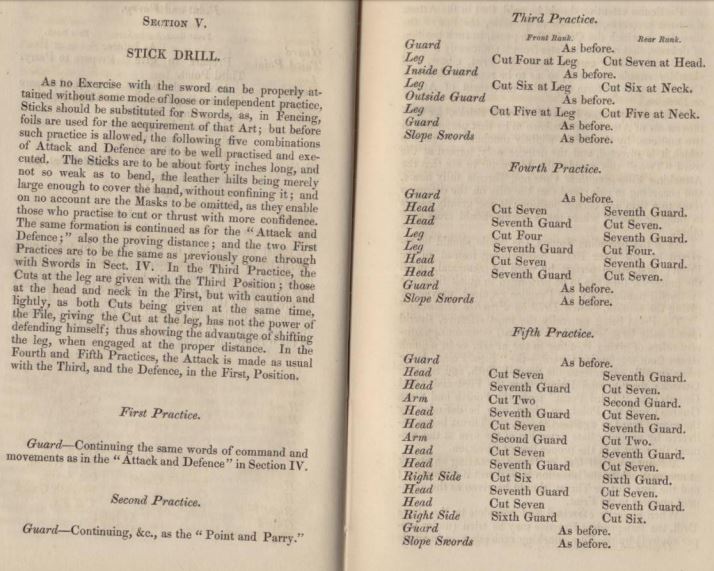

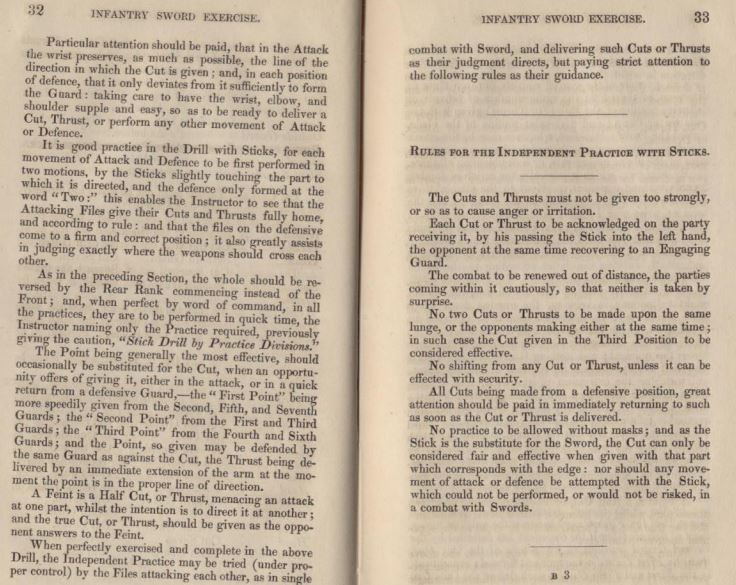

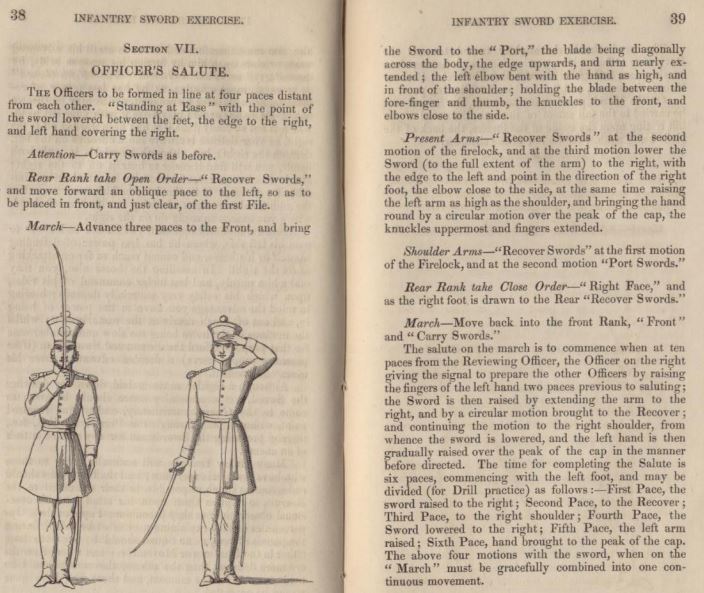

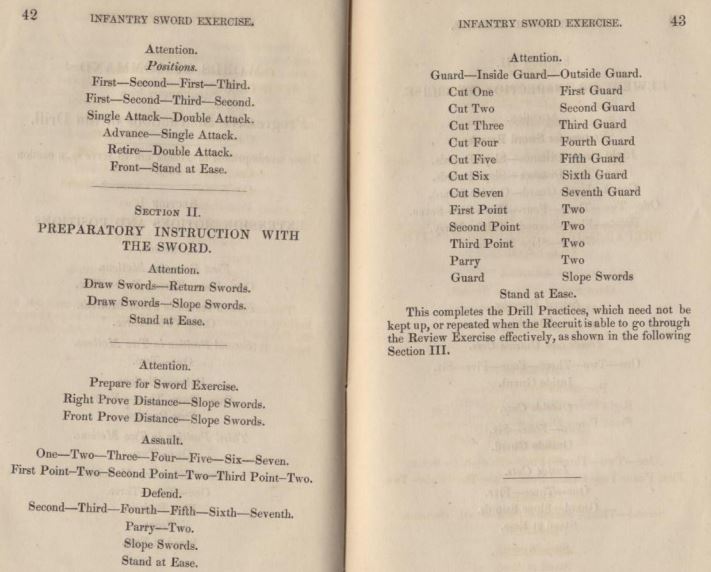

His son, Henry Charles ‘the younger’ (1780-1852) took over the Angelo School of Arms in 1817. That same year, he published the Rules and Regulations for the Infantry Sword Exercise (1817), which was adopted by the army and made a standard manual. He followed this publication, in 1842, with Infantry Sword Exercise. Infantry Sword Exercise remained the standard training manual for the next 50 years and continued to be republished until at least the 1870’s. (This is the work extensively criticized by Sir Richard Francis Burton.) Henry Charles also authored Angelo’s Bayonet Exercise, which like his Sword Exercise, became a standard used by British armed forces. It was republished in 1853 and 1857, no doubt much to the chagrin of Sir Richard Francis Burton, whose own bayonet treatise of 1853 had been passed over. It was only after the new thrusting blade type, introduced in 1892, that Angelo’s manual was replaced, in 1895 by Maestro Masiello’s Infantry Sword Exercise.

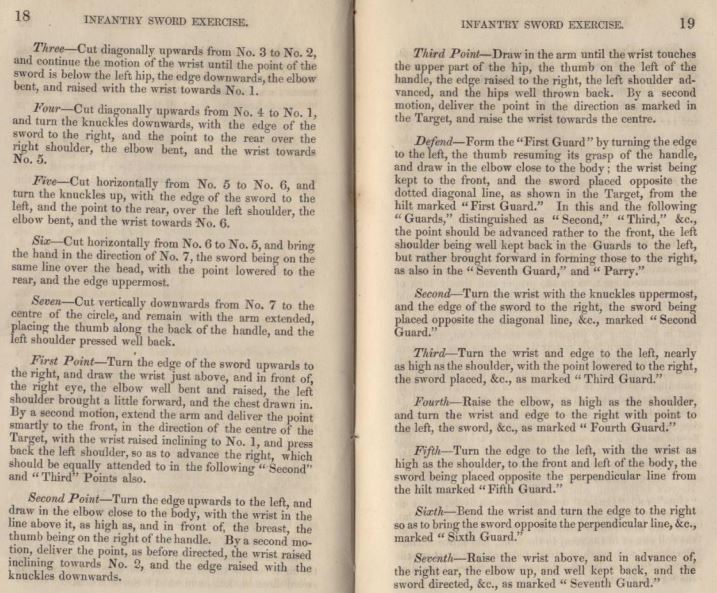

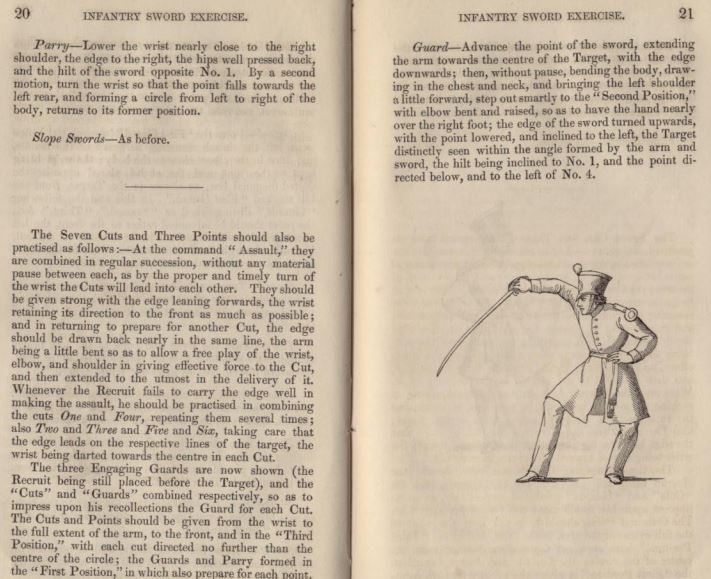

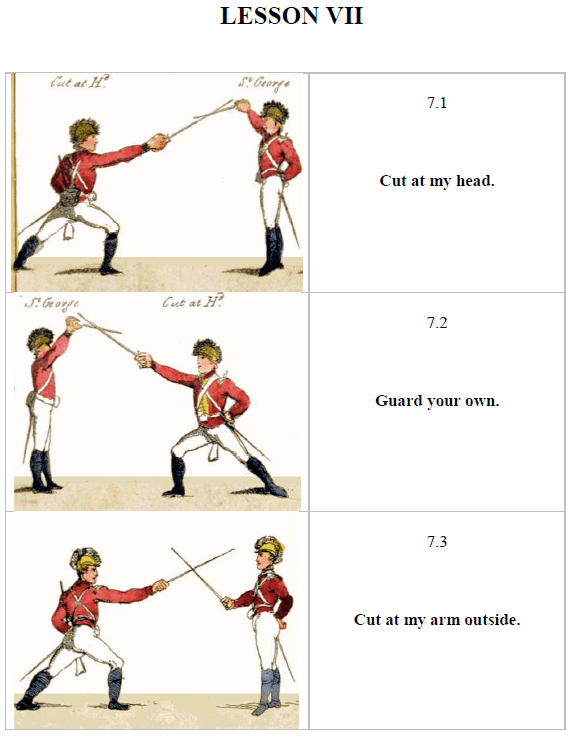

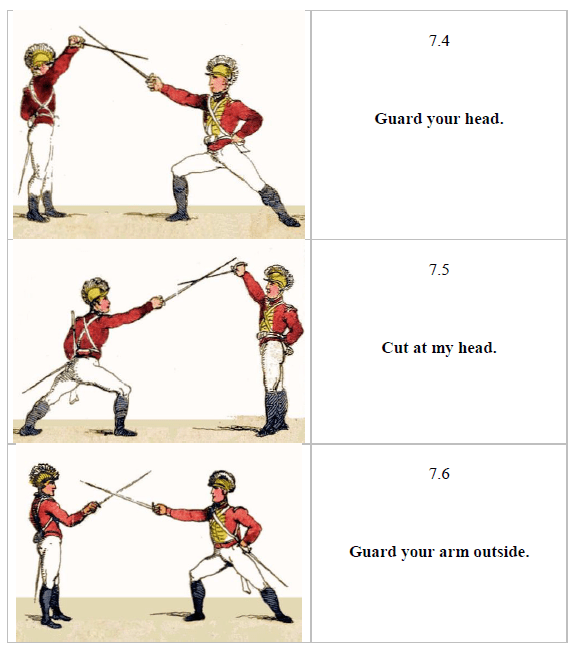

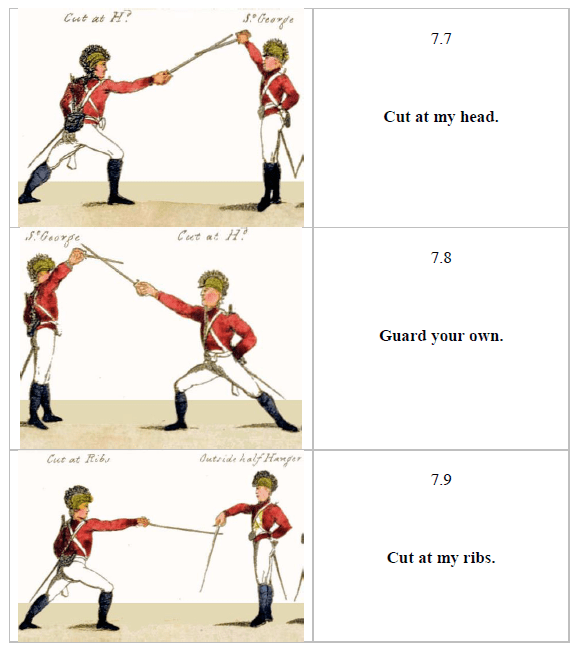

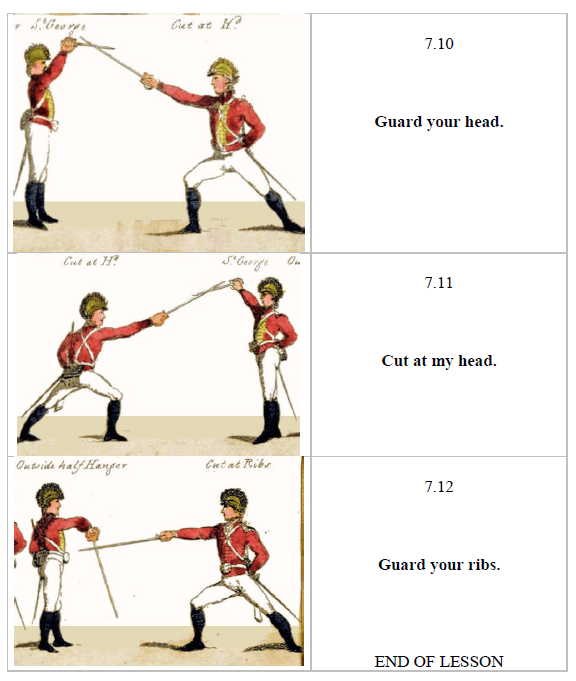

Because Infantry Sword Exercise is a training manual for soldiers, it is simple when compared with earlier manuals intended for serious practitioners of the blade. Technical proficiency is all a soldier needs – not mastery.

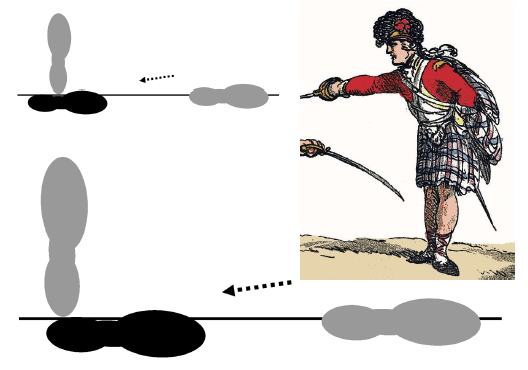

Henry Angelo’s broadsword exercises

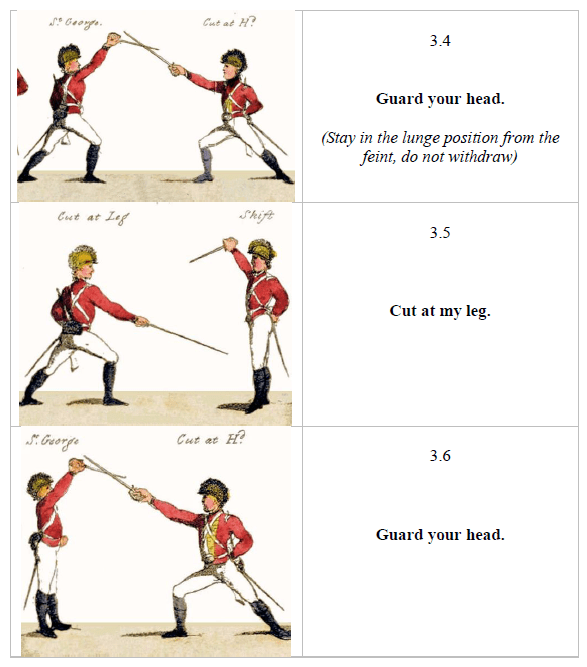

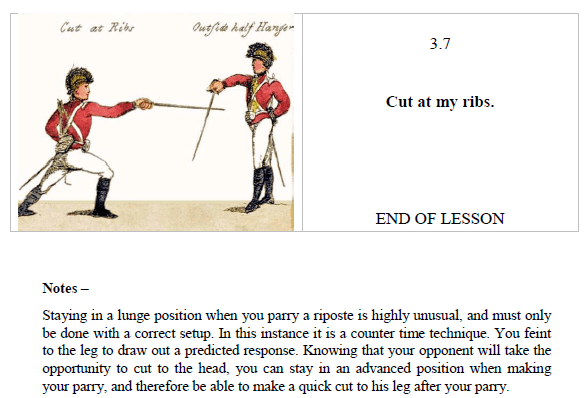

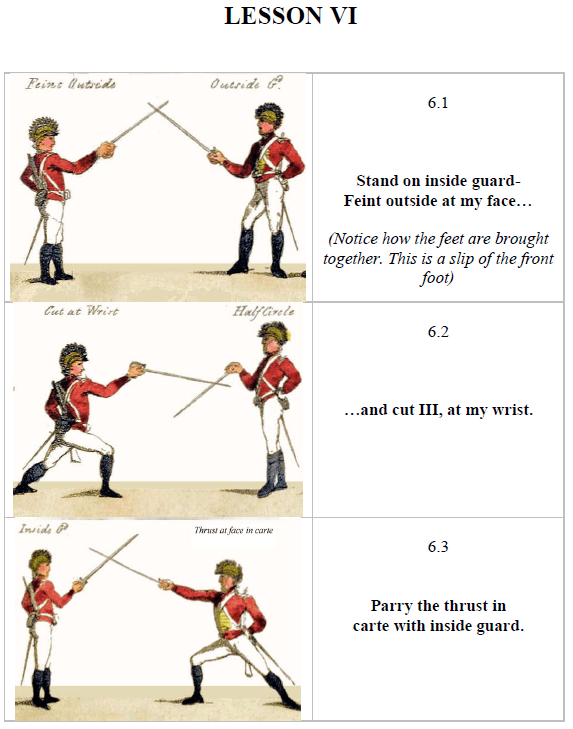

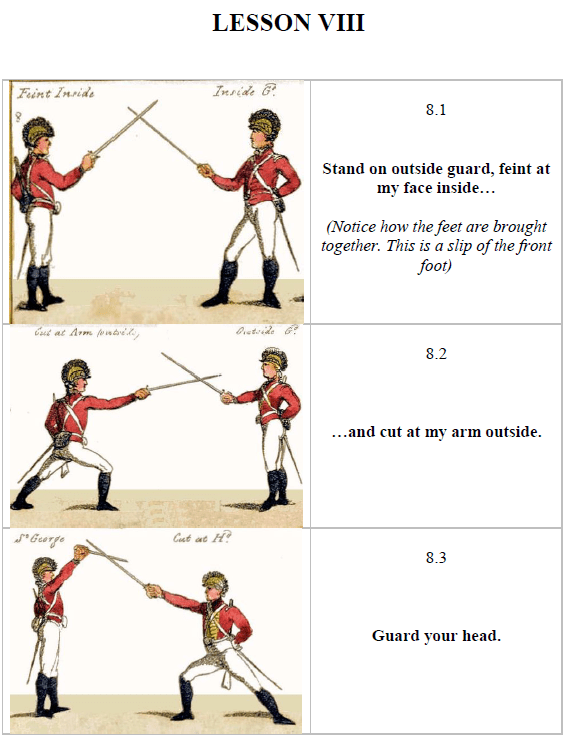

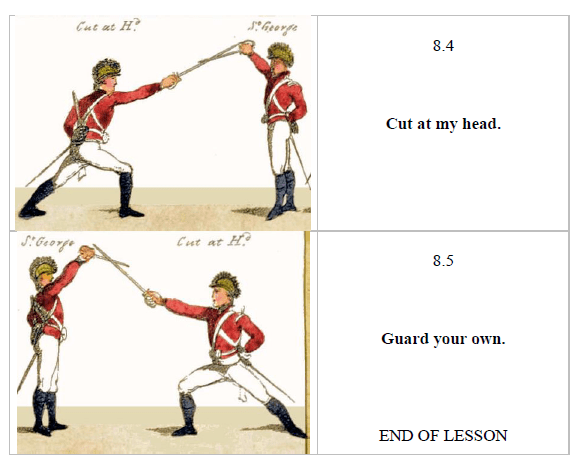

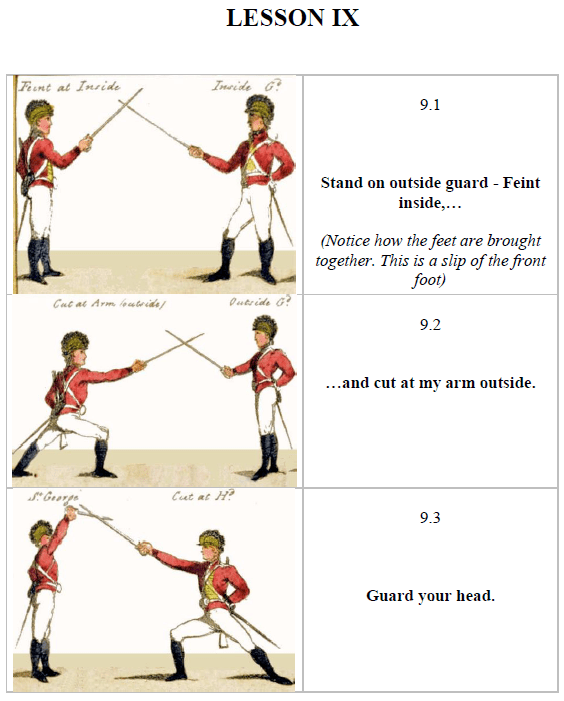

Bringing the feet together is common when parrying, but it is done by withdrawing, or slipping the front leg. Angelo never says which foot moves at the start of this lesson when the feint is made, but it is logical that the front leg is withdrawn for the following reasons:

To protect it during the feint, like in lesson 2 when the body is held back while lunging; to create an illusion of attack/threat and thereby provoke a response to the feint; the system relies on being able to slip the leg to stop it being struck, but if you brought up the rear foot, both would be in range; and, If you started at lunge distance (as you should), brought the rear leg up, and then lunged, you would be too close to your opponent.

This is a military system practiced/drilled in formation. At no time does the back leg ever move, because to do so would completely mess up the formation of the practice. This is not a reason to do what you do, but an explanation as to reinforce the prior points.

The thrust in 9.8 is very different from the Angelo poster, which does not show thrusts, and we do not know how it is parried in this drill. However, in Roworth’s text he says the most usual method of parrying thrusts made above the wrist are using outside and inside guard. Typically with a beat, and with a slightly more bent arm and lowered guard.

HOW ANGELO’S LESSONS DIFFER FROM ROWORTH‘S

The only significant difference is the inclusion of thrust work in Roworth’s edition, where you must both parry and launch thrusts yourself, as opposed to Angelo where there is no thrust work from either party.

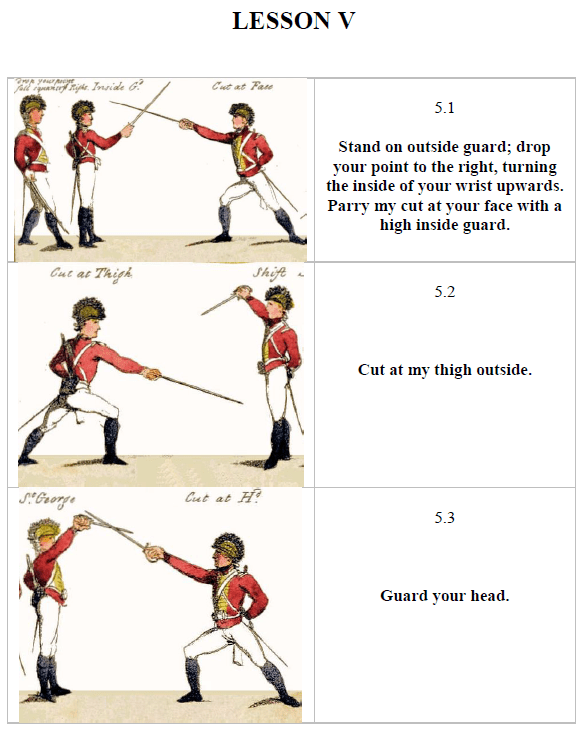

V – Guard your own added at end as an additional action.

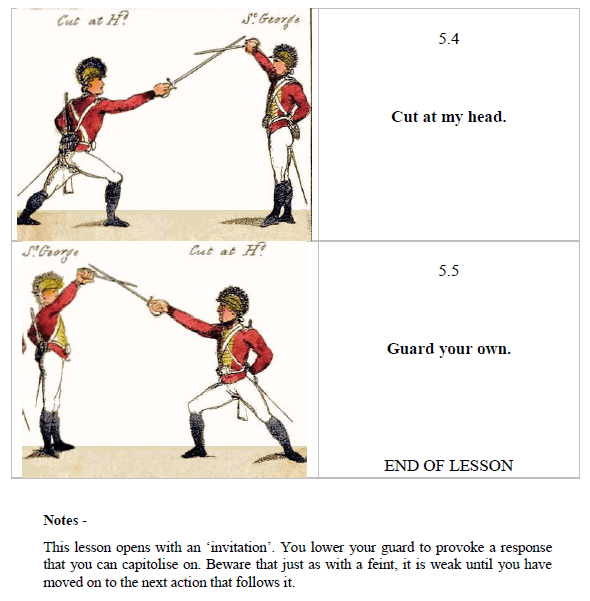

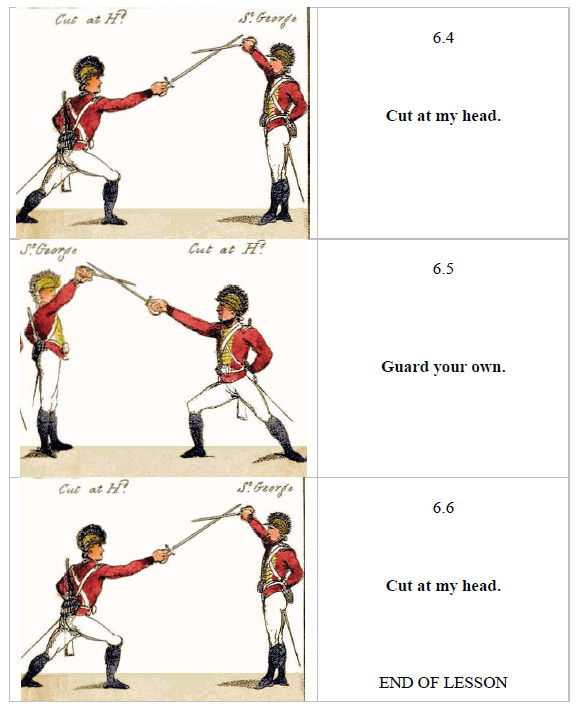

VI – First two actions are the same, but after the parry is made from your cut 3, go to outside guard, then feint inside to his face, before cutting to his ribs, A answers feint by coming to inside guard and then parrying rib cut with the outside half hanger.

IX – Differs radically after the first few actions due to the inclusion of thrust work in Roworth.

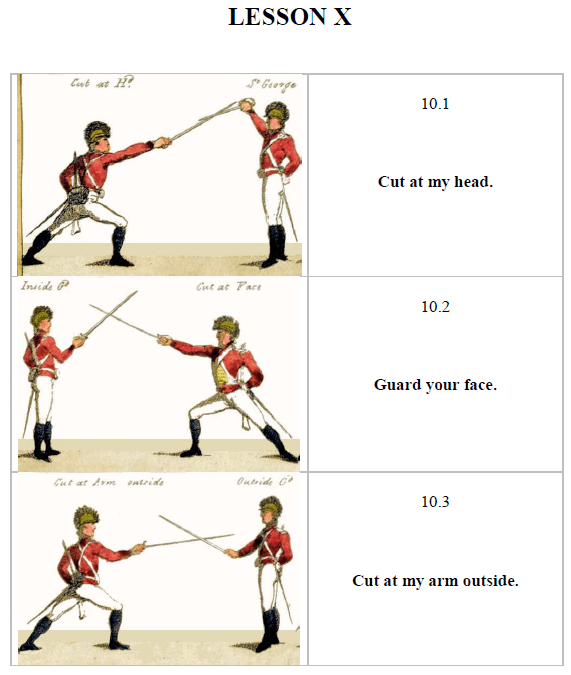

X – Overall the actions are the same, except some target zones aimed for are changed between face and breast.

COMMON QUESTIONS

Why always withdraw the lead leg?

Roworth never says to always slip the leg when parrying, except for certain parries, however the Angelo poster is far clearer on the subject. The slip of the leg is because you can easily be deceived when parrying through feints, or hit with a second re-directed hit after you have made your parry. Even if you can make your counter attack and land a blow, you do not want to have been cut in the leg yourself. Always practicing the leg slip instils a strong defensive mind-set into a swordsman. We have also found that as a result it makes for a cleaner, safe fight, with far less risk of double hits.

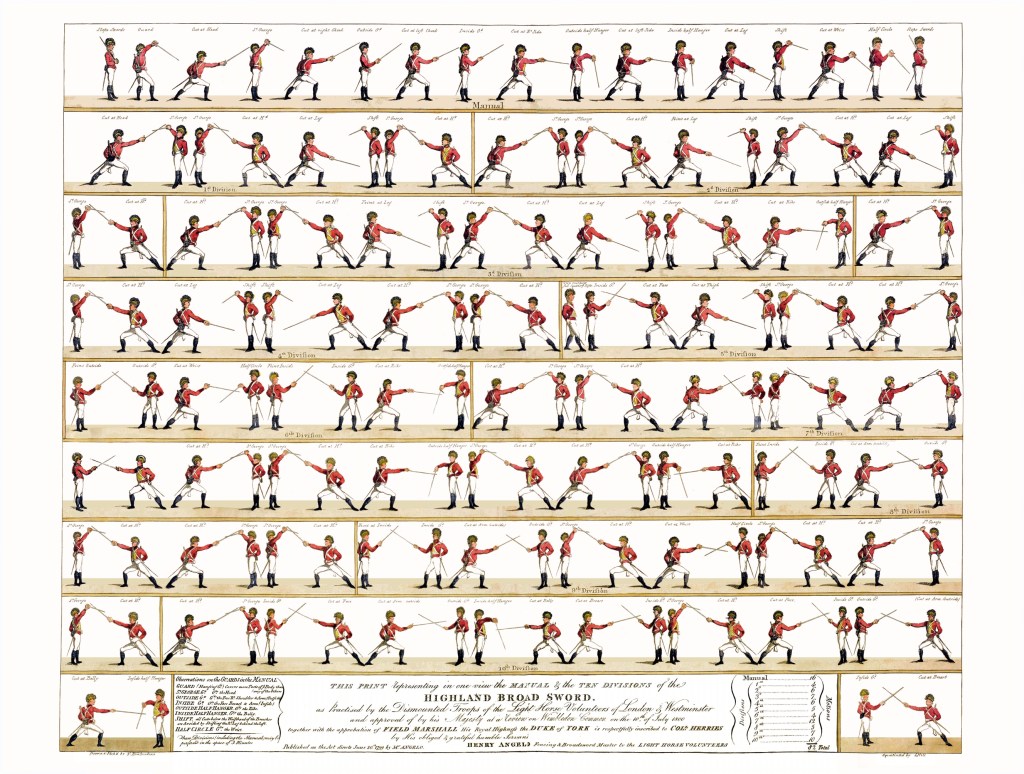

Why cut to the outside leg rather than inside?

When you have parried in the Guard of St. George, you might find it more natural, and more powerful to cut to the inside of your opponent’s leg, rather than the outside as is shown in every lesson. However, if during or after the cut you need to change what you are doing, or parry some kind of counter, you will have a much stronger defence when cutting outside than inside. When delivering a cut to the outside leg as either a determined attack, or a feint, you can return to Hanging guard or St George extremely quickly. But when cutting to the inside, the natural guard posture for defence is half circle guard, which is very weak when met with a heavy cut from high, and makes the hand very vulnerable. Another point that we have found is that when fighting in close order, as many battlefield fights would be, cutting to the inside leg of your opponent requires an awful lot of space. To do so can require cutting across, or interfering with the comrade to your right, but a cut to the outside is very self contained between you and your opponent.

Why use Guard of St George instead of Seconde hanging/Outside Hanging guard?

Because it is stronger, and Angelo teaches much the same. He says to use inside and outside guard to defend against cuts to the face (cut 1 & 2), but St George to defend against a powerful straight cut to the top of the head (cut 7). It is much harder to beat through St George, and also, against a straight cut, seconde hanging guard can endanger the lead hand as it brings the guard in line to the opponent’s cut.

Is it dangerous to cut to the leg under a high parry?

Yes, in fact attacking the legs is generally dangerous anyway. As you are cutting low you lose some reach, with what we call the ‘false distance’, because you are cutting from shoulder height and aiming low. Not only this but you cannot protect your head, and without the cover of a buckler or shield, you cannot cover whilst attacking. To make a leg cut safer, you need to set up the situation to make it safer. Examples of this are seen in Lesson 2, and lesson 5. Cutting to the leg and not being struck on your arm or head is actually quite difficult, and often a dangerous task for even a well trained swordsman.

Is it all linear?

Everything in these lessons is practiced in lines, and the only movement is back and forth. However, there is some non-linear footwork in Roworth’s system, but it is unusual. It is rare to ever use offline footwork, meaning some kind of circular, or sideways motions around your opponent, except in the case of negotiating difficult terrain or to move out of the irritation of sunlight etc. In essence, it is almost entirely a linear system, for the sake of efficiency, and limited room to manoeuvre in many military combat situations.

Why keep the left hand behind the back?

The sabre and broadsword are very agile weapons, whilst being very powerful in their cuts as well. However they are typically not used with an offhand weapon in British military swordsmanship. The shoulders need to be kept in line with the offhand being back for reach, and to leave the hand out will only make it a target. The left hand should only come forward at that moment in time it is needed to cover an opponent’s sword, to disarm, or to punch them in the face, should you get so close. That being said, Roworth says that the hand can be rested down or behind as seen in the Angelo text, or up beside the face to use as a counter balance should you wish to. But the most important thing is that it stays safe and out of the way.

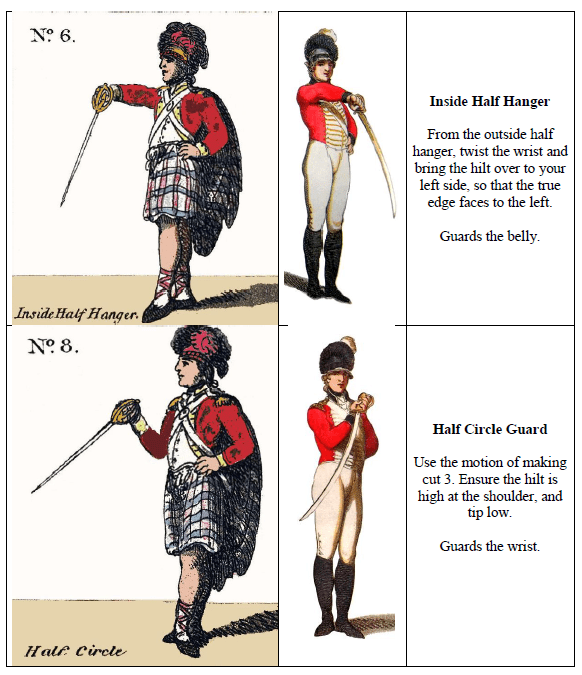

Why use Half Circle Guard?

This guard may feel both strange and weak, and in most instances it is. However, it is an excellent way to quickly parry snipes to the wrist made on the inside. In the first edition of Roworth, he taught what he called inside guard second and third position to in part deal with this. However in his second edition (1798) and 1804 edition, these were removed. This parry is especially useful when you are using a simple stirrup hilt sabre that does not have much hand protection, and therefore allows little margin for error if you attempt to parry with inside guard.

_____________

Burton’s manual to compare and contrast against Angelo’s.

_____________

Alfred Hutton’s Old Sword Play (1892) anthologized the various forms from the 16th to 18th centuries that lead to the then current forms.

_____________

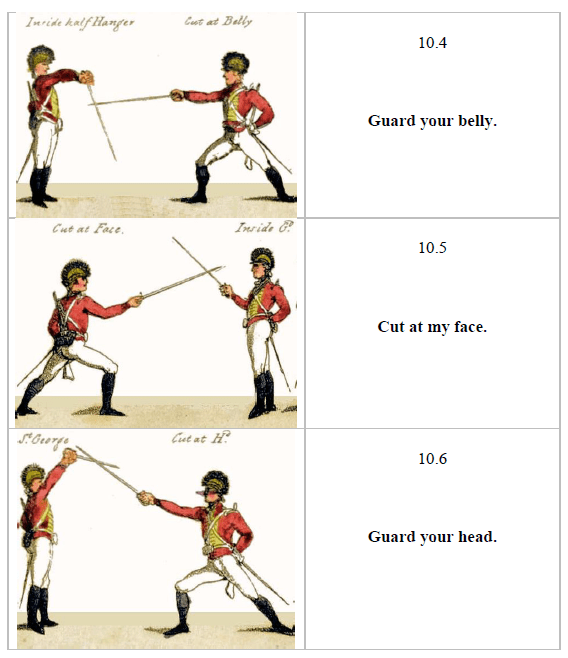

The Art of Defence on Foot by C. Roworth (1804) contains very similar lessons and nicely compliment the manual of arms by the Angelos.

Purpose of These Lessons

These lessons were created and taught at a time of increasing standardisation in training, equipment and tactics within the British armed forces. This would require training large bodies of troops in a regimented and disciplined fashion. The methods shown here were not just for officers, as some might assume, but for all those who carried swords. That would include cavalry, as they needed to know how to fight on foot as well as horseback, but it would also include infantry officers, Royal Navy crews, some light infantry, including rifleman, artillerymen, militia and more.

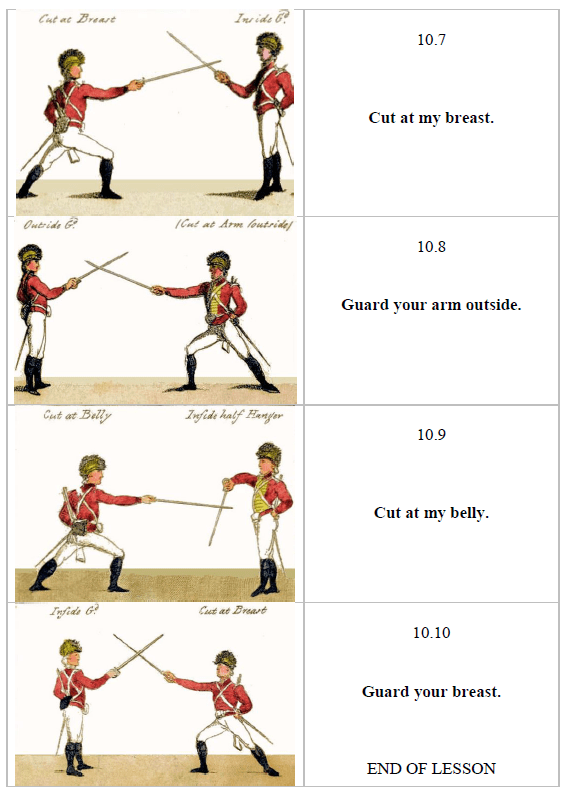

The ten lessons are a simple and effective way for large bodies of men to learn a great range of techniques, and simulate a range of realistic scenarios. It teaches a swordsman a full range of attacks and defences, feints and counters. It also builds a range of responses and instills an importance in defending the most important target – the head. In fact in the ten lessons shown in Roworth’s manual are to be found the vast majority of the sabre and broadsword method of fight.

In essence, with regular practice of these ten lessons, you will have a well rounded understanding of military swordsmanship on foot. But there is always more to learn, and I would recommend you read further. Roworth’s manual includes a great range of advice and further exercises and advice that may be useful and interesting. To begin the ten lessons, you need the basic fundamentals shown in the following pages.

Grip

Later styles of sabre use a grip where the thumb rests on the backstrap, or back of the grip, pointing up the length of the blade. Roworth tells us that this is not well suited to the heavy swords, and/or heavily curved blades commonly used in his day, except for the spadroon. Additionally, an enclosed Scottish broadsword (basket hilt) does not have the space for this. As a result, the sword for this system is held in what we call a ‘hammer grip’. This is the instinctive way to hold the grip, just like you would a hammer. Do not grip too tightly though, remain supple with your grip.

Stance

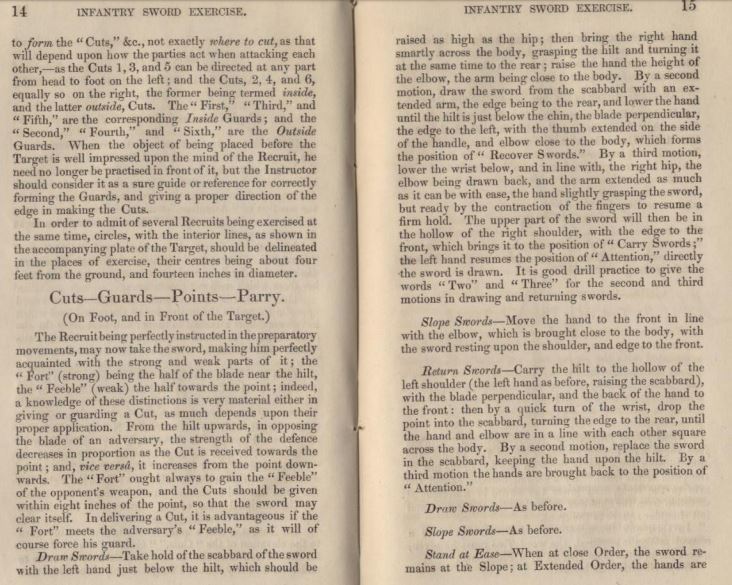

Both Roworth and Angelo show the same posture with the body throughout all guards. The feet should be roughly shoulder width apart (14-16 inches). The front foot should point straight towards your opponent, your rear foot should turn to the left, at roughly 90 degrees to the front foot (or pointing a little forward or back from here). The back knee should be bent in the direction of the back foot. Most of the bodyweight should be on the back foot, so that you can quickly lunge, or slip the front foot without having to adjust your weight.

The body should be well in line, so that your right shoulder faces forward to your opponent, and your left shoulder is drawn well back.

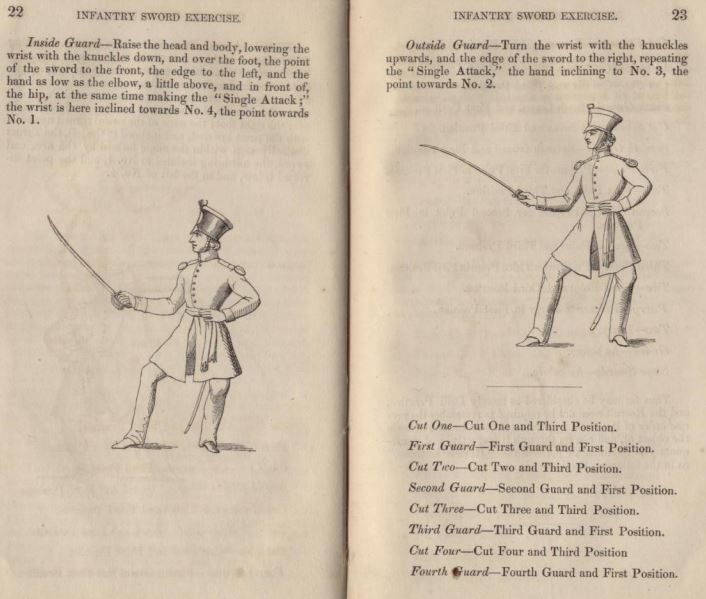

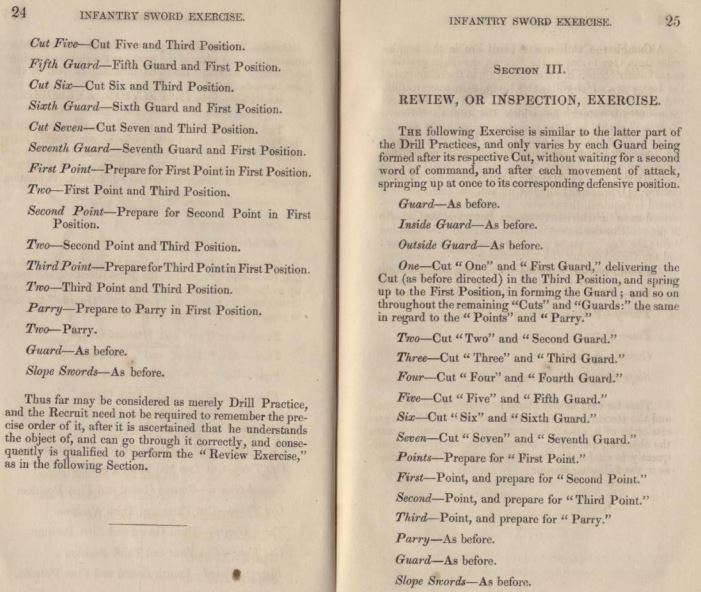

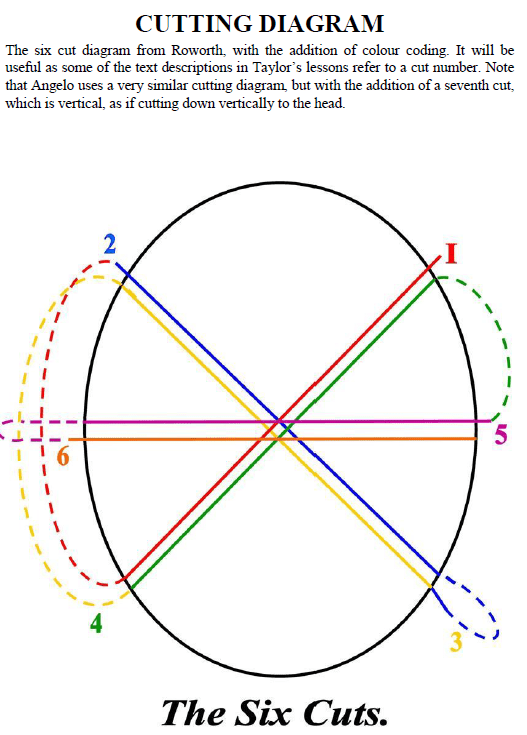

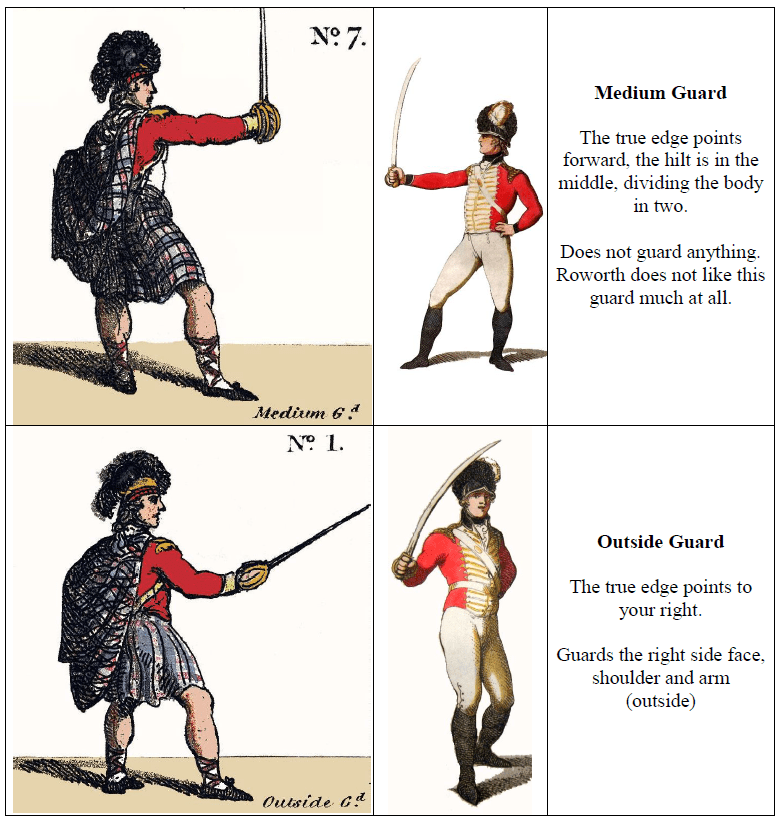

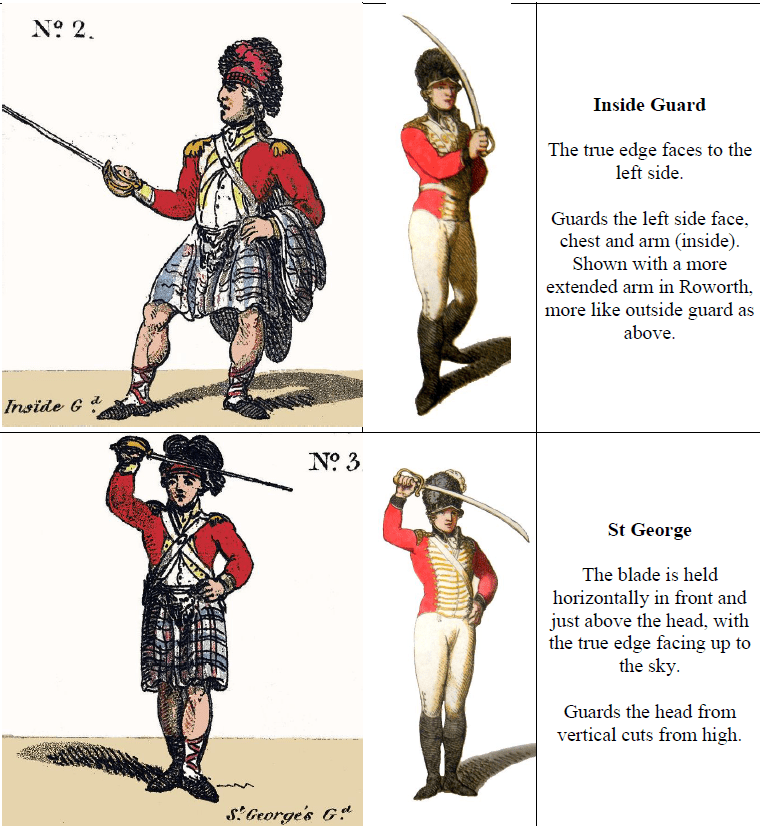

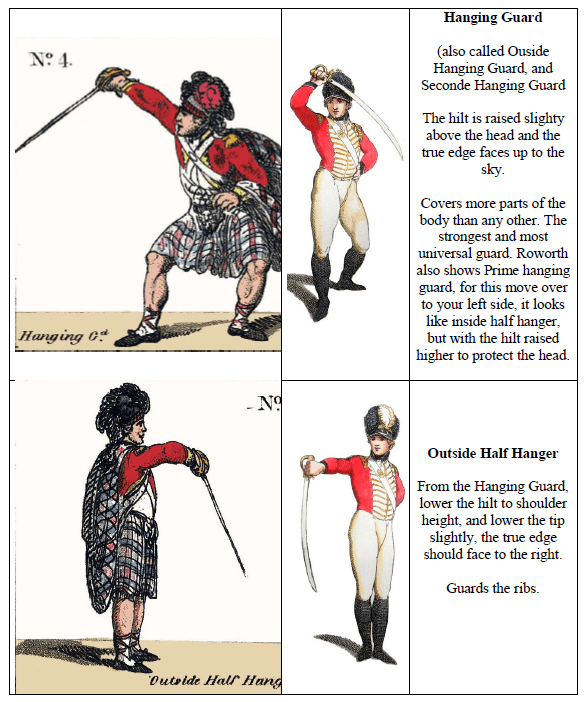

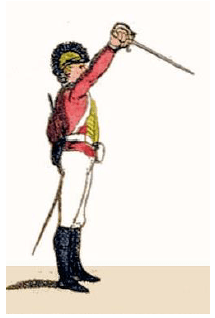

Guards

The guard positions are both positions to stand in at wide measure, and also positions with which to parry your opponents attacks.

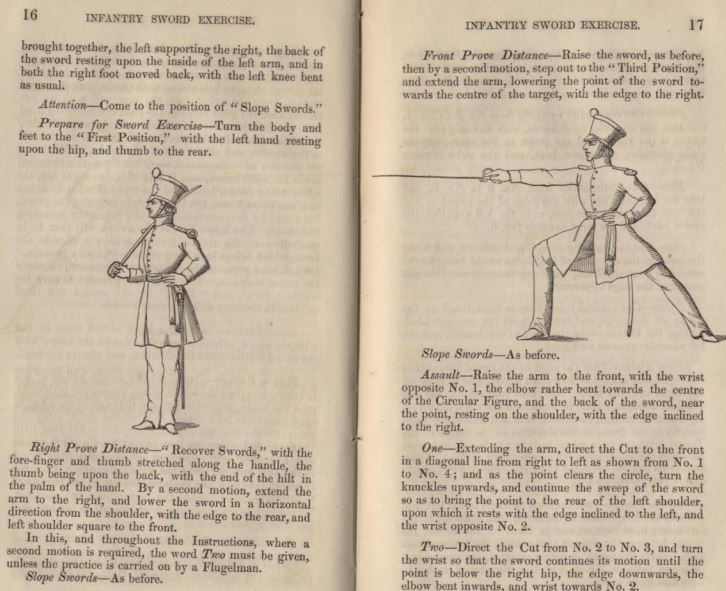

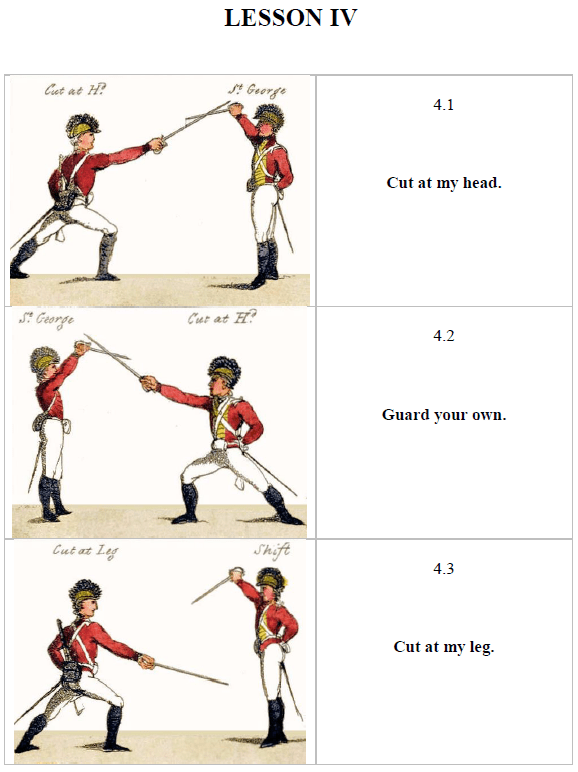

Lunge

The lunge is an attack where you advance your front foot and use your whole body to reach for an attack, but without moving the rear foot. It is the standard method of attacking in Broadsword/Sabre. It can be a cut or thrust. Make sure to keep your right shoulder forward and left shoulder back. Move your front foot forward the length of about a shoe to shoe and a half, and bend the front knee, and ensure the sword arm is extended in whatever attack you are making. Always ensure the back foot stays firm and planted, and that the back leg straightens to give speed. The front foot is pointing forward towards your opponent just like it was in guard. Do not take too large a step. Do not reach too far with the body as would be typical of a lunge in rapier. An excessively long lunge is dangerous as it is too slow to recover from with the fast counter cutting in broadsword and sabre.

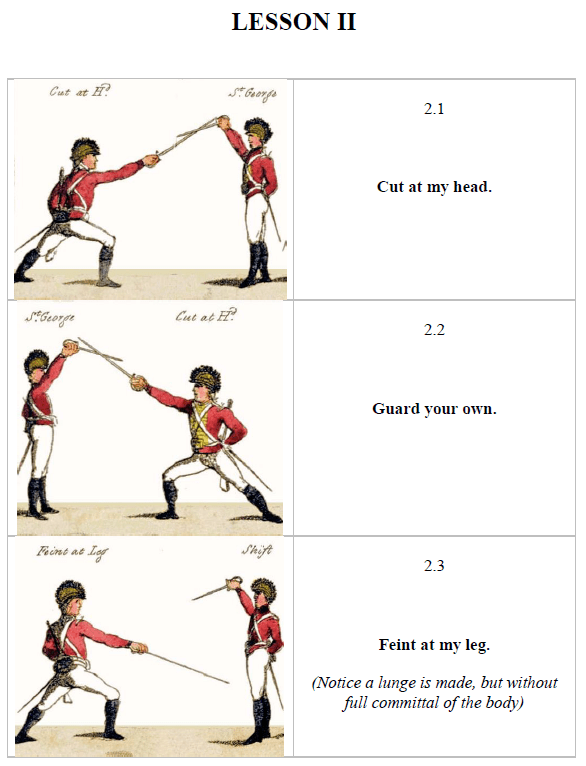

Slip

Slipping the leg simply means to withdraw the lead foot back to the rear foot as the diagrams show. However a slip can also mean to withdraw that target which your opponent is aiming at, as to strike them in response without a parry. In Angelo’s lessons, the leg is always slipped when a parry is made, unless there is a specific reason not to, such as staying in a lunge position after a feint in lesson 2. The leg is slipped no matter whether your opponent is aiming at your leg or anywhere else. This is because they can easily redirect, and/or feint to cut at the leg. Roworth shows the slip of the leg position being a perpendicular angle, but illustrations from Angelo’s work vary from being the same to having both feet pointing forwards. The important thing is that you withdraw the lead leg to where the rear leg was positioned. Roworth says to bring the middle of the lead foot back to the heel as in the first diagram below, other descriptions of this move have the heels being brought together in in the second diagram.

Start Position

Opponents should start at the correct distance between one another. That is the

distance where a lunge is required to strike your opponent’s head/body when they are in guard, this is commonly called wide measure. (Narrow measure being the distance at which you can strike your opponent without stepping).

Angelo’s lessons always begin in seconde hanging guard (outside hanging guard),

unless otherwise stated. Roworth also begins many exercises from outside guard.

Either is fine, but for the sake of discipline I’d be inclinded to stick with Angelo’s

Hanging guard unless it says otherwise.

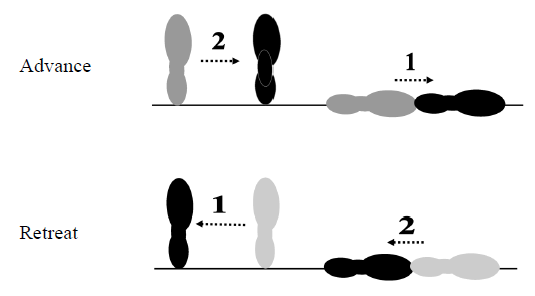

Footwork

Every attack is made with a lunge, unless mentioned in the notes.

Every parry is made by withdrawing the lead foot (slip) so that it rests beside the rear foot, unless specifically mentioned. Only move one foot during each action. Moving both feet is slow.

The basic method of adjusting distanee. To move forward extend the front foot and

then bring the back foot up to return to guard. To retreat, move the back foot first, and then the front one follows

One thought on “HENRY CHARLES ANGELO”