In the BBC Sherlock, series, both Holmes and his adversary Charles Augustus Magnussen demonstrate a disciplined version of the method of loci, the so-called “Memory Palace.” Sherlock stores libraries of information in imagined corridors and retrieves them at will, solving cases and saving himself from peril by walking the halls of his own mind.

I first saw someone use a memory palace in real life during my freshman year at Reed. The class was billed as “science for poets,” a supposed reprieve from the rigors of biology and chemistry, held in Vollum Hall. The instructor introduced himself as Stavros Theodorakis. He was teaching in America to avoid military service in Greece. He was intense, brilliant, and serious about imparting observational frame reference equations. He promised that by semester’s end we would “know as much particle physics as any graduate student.”

He then asked every student’s name, once, in a hall of over a hundred. At the end of the hour, he dismissed us individually. By name. A name which had heard precisely once from a hall of students he had never previously met.

He also offered a challenge: anyone who could replicate his feat would receive an “A” and be excused from class for the rest of the term. No one even tried.

Years later stumbled upon Frances Yates’s, The Art of Memory (1966), a luminous history of the classical techniques of recall. I read a few chapters and, predictably, attempted to build a palace of my own. I was inconsistent, impatient, and unsuccessful. The first room never formed.

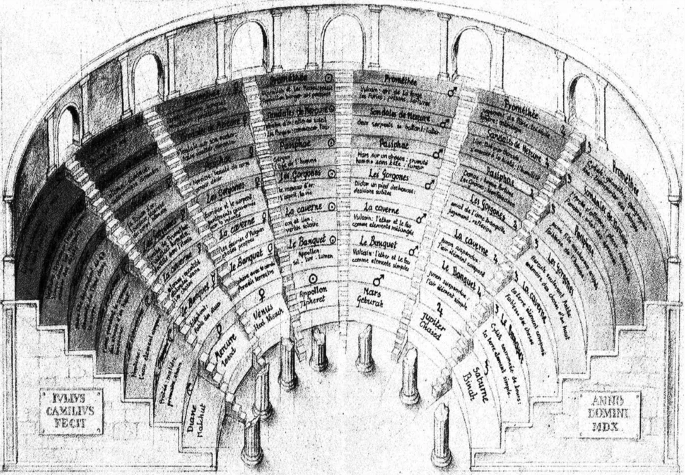

The method, as first described in Rhetorica ad Herennium, a text long attributed to Cicero, divides memory into the natural and the artificial. Natural memory is the gift we are born with; artificial memory is its cultivated twin, strengthened through discipline and architecture.

“The artificial memory includes locations and images. By locations I mean such scenes as are naturally or artificially set off on a small scale…for example, a house, an intercolumnar space, a recess, an arch. An image is a figure, mark, or portrait of the object we wish to remember….”

—Ad Herennium, III.28–30

Greek and Roman orators depended on such architecture to deliver their speeches without notes. In an oral culture, persuasion was built not on manuscripts but on memory.

Wired Magazine offered a primer with an embedded link on how to build a memory palace; there are now entire websites devoted to selling the discipline as a life-hack.

Yet there is something more profound at stake. The art of memory is not about efficiency; it is about presence. To remember is to inhabit one’s own interior landscape.

Umberto Eco, quoting Plato’s Phaedrus, retells the story of Theut presenting the invention of writing to Pharaoh Thamus. Writing, Theut claimed, would help people remember what they might otherwise forget. Thamus replied that it would do the opposite: it would make people rely on external devices instead of exercising their internal memory.

Plato was of course writing down his argument against writing, a delicious irony, but his warning survives every technological age. Books did not narcotize memory, as Eco reminds us; they refined it. But each new invention rekindles the same fear: that what we offload to our tools, we lose in ourselves.

The Pharaoh’s caution feels newly relevant. Our memories now live in clouds and feeds, indexed by algorithms rather than imagination. The palace of the mind is dissolving into data.

We have not lost the gift of memory; we have merely outsourced the labor.

________________

Slate remembering Frances Yates

Google Books digital version of The Art of Memory

________________

Connected with memory is learning – often the two can be conflated, such that to remember a fact or skill is to have learned it – yet >this< article argues that we still learn inefficiently.

One thought on “Memory Palace”