Sing, Goddess, Achilles’ rage,

Black and murderous, that cost the Greeks

Incalculable pain, pitched countless souls

Of heroes into Hades’ dark,

And left their bodies to rot as feasts

For dogs and birds, as Zeus’ will was done.

Begin with the clash between Agamemnon–

The Greek warlord–and godlike Achilles.

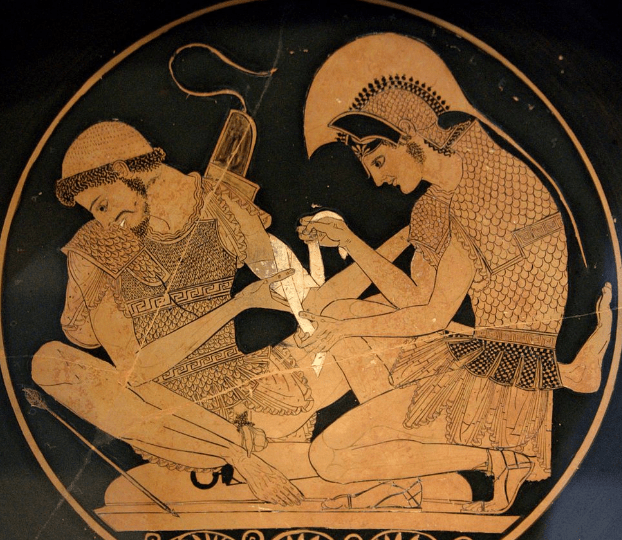

So opens the Illiad. Homer focuses our attention on the combatants: this is an epic struggle between two Greeks, Achilles against Agamemnon, even if the bulk of the verses are about the gristly combat of Greek against Trojan.

Achilles retreats to his tent and refuses to enter into combat because Agamemnon took honor from him (Briseis). We moderns need to understand that this isn’t just a personal insult leading to a sulking response (even if Achilles was in fact a petulant teen-ager).[1]

Achilles’ rage results from the loss of honor, not personal pride, but his standing. His standing amongst his fellow kings is diminished by Agamemnon. In a positional culture where your worth is determined by the honors others bestow upon you, this public taking by Agamemnon is a direct insult and an overt power play.

Achilles withdraws from combat (elite competition par excellence) to show everyone precisely how necessary he is to Greek success. He is the greatest warrior and he will prove it with the pain of his absence and triumphantly with his dominating return.

The ancient Greeks were competitors bar none. They fought with everyone and defined the world competitively to demonstrate arête – excellence. Ancient Greek education (paideia) sought to teach the ideals of moral (and practical) excellence and the Greeks split the world in a binary manner – you either shared the ideals of paideia or you didn’t. Arête was an ideal to achieve and the binding concept which demands contest. The Greeks awarded prizes for excellence and competed in everything. They were the first “best of…” list makers. In Book 23 of the Iliad, right after Achilles kills Hector, the Greeks return to camp, blood splattered but victorious, to honor Patroklos with a funeral pyre and games of competition. They nominate judges and name prizes to be awarded the winners of each contest; the best charioteer, the best boxer, the best wrestler, spear fighter, etc., all of whom struggle (at grave personal risk) to prove their excellence.

The Greeks perfected this elite contest and all the quarrelsome city-states sent their very best to compete before the gods at the Sanctuary of Zeus in Elis. That site, Achaia Olympia, gives us the name for the Olympics.

The Olympics celebrate the pinnacle of human achievement, show us the limits of what the human body and spirit can achieve, and provide exemplars of what we should all strive for – that binding and galvanizing sense of paideia.

How far we have fallen. What a travesty these once-great games have become! I am aghast to see the talking heads laud Simone Biles for walking away in the middle of competition. The media is calling her brave? That is linguistic corruption—doublespeak at its best. That is the very opposite of the definition of bravery. This coddle-culture that celebrates weakness has infected the very ideals of elite athletic performance.

The ancients would not have understood this inversion. For them, failure was instruction, pain was proof of striving, and competition itself was sacred.

Imagine other elites using the same failure-logic. “Sorry general, but Seal Team 6 is having a mental health day…” Ludicrous! It’s absurd, and it reveals how far the contagion of fragility has spread. We are discussing the best in the world who have trained mercilessly for years, dedicated their entire lives to show us the tested limits of human physical achievement. For the media to focus on and celebrate Simone’s failure of will is a travesty and diminishes the accomplishments of the other athletes.

Achilles walked away from the battle to provide a context that would force everyone to know with visceral pain that he was the greatest of all time. Simone – you ain’t no GOAT – you gave up. You just taught the next generation of elite athletes that it is okay to quit – in the middle of the Olympics! Quit before you get there so that people who can handle the pressure get to show what they are capable of.

I imagine that Piers Morgan will be castigated for having the courage to say what needed to be said: Sorry Simone Biles, but there’s nothing heroic or brave about quitting because you’re not having ‘fun’ – you let down your team-mates, your fans and your country. As a culture, we need to get our shit together and stop celebrating failure.

I know if this post were widely read I would be chastised by all those who believe mental health issues should be given more prominence because they are real health problems. Yes, I know mental health issues are real. But that isn’t the point. The point is that while mental health issues deserve compassion and treatment, they should not be confused with heroism. They need to be addressed privately, not celebrated publicly as examples of courage.

And most importantly, it has no place in conversations about elite performance. By definition, the elite are those who perform under conditions that would break ordinary people.

The Greeks understood this truth instinctively: excellence demands cost, honor requires endurance, and civilization is built by those who refuse to quit.

_____________________

[1] Ruth Benedict popularized the shame vs guilt cultural description in her The Chrysanthemum and the Sword. The terminology is broad-stroke and sociological refinements like Emmanuel Todd‘s shift the focus, but remain essentially an analysis of how individual psychology is culturally constrained. A more recent global survey was just published (Sept. 2021) by the National Bureau of Economic Research: Herding, Warfare, and a Culture of Honor. It is a global survey of Shame societies:

According to the widely known ‘culture of honor’ hypothesis from social psychology, traditional herding practices are believed to have generated a value system that is conducive to revenge-taking and violence. We test this idea at a global scale using a combination of ethnographic records, historical folklore information, global data on contemporary conflict events, and large-scale surveys. The data show systematic links between traditional herding practices and a culture of honor. First, the culture of pre-industrial societies that relied on animal herding emphasizes violence, punishment, and revenge-taking. Second, contemporary ethnolinguistic groups that historically subsisted more strongly on herding have more frequent and severe conflict today. Third, the contemporary descendants of herders report being more willing to take revenge and punish unfair behavior in the globally representative Global Preferences Survey. In all, the evidence supports the idea that this form of economic subsistence generated a functional psychology that has persisted until today and plays a role in shaping conflict across the globe.

One thought on “Elite Competition”