I admire my Uncle Tony tremendously. A common-sense New Englander, Chicago-trained lawyer, who is now in his 80s and remains intellectually active. With an odd synchronicity, independently we both re-watched Patton (1970). It is a brilliant movie that underscores the grave importance Patton had in winning World War 2 while still showing his human flaws. An intelligent and balanced portrayal of a great man.

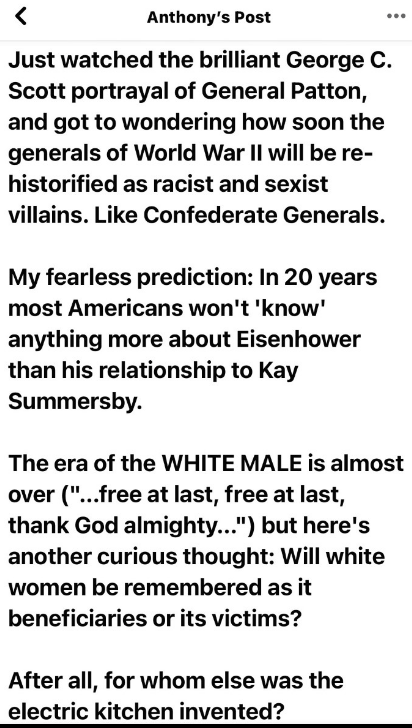

As we watch statues fall to the bleating ignorance of cancel culture, my uncle mused:

His bitter irony is more pronounced now: he has the freedom to speak truth because there are no consequences he fears. And the truth he points to is the fallacy of judging the past with the prejudices of the present. It is a high form of arrogance that presumes not only that the current norms are somehow in fact “better” but also presupposes an understanding of the conditions of the past. A double fallacy. Simply stated, Patton is too important to let current pathological concerns diminish his accomplishments and merits.

Victor Hanson covers Patton’s importance in preserving democracy in The Soul of Battle (1999) and has continued to extol him:

Hanson’s summary:

“Nearly 70 years ago, on Aug. 1, 1944, Lieutenant General George S. Patton took command of the American Third Army in France. For the next 30 days, they rolled straight toward the German border.

Patton almost missed his summer of glory. After brilliant service in North Africa and Sicily, fellow officers considered him the most gifted American field general of his generation. But near the conclusion of his illustrious Sicilian campaign, the volatile Patton slapped two sick GIs in field hospitals, raving that they were shirkers. In truth, both were ill and at least one was suffering from malaria.

Public outrage eventually followed the shameful incidents. As a result, Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower was forced to put Patton on ice for 11 key months.

Tragically, Patton’s irreplaceable talents would be lost to the Allies in the stagnant Italian campaign. He also played no real role in the planning of the Normandy campaign. Instead, his former subordinate, the more stable but far less gifted Omar Bradley, assumed direct command under Eisenhower of American armies in France.

In early 1944, a mythical Patton army was used as a deception to fool the Germans into thinking that “Army Group Patton” might still make another major landing at Calais. The Germans apparently found it incomprehensible that the Americans would bench their most audacious general at the very moment when his audacity was most needed.

When Patton’s Third Army finally became operational seven weeks after D-Day, it was supposed to play only a secondary role — guarding the southern flank of the armies of Gen. Bradley and British Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery while securing the Atlantic ports.

Despite having the longest route to the German border, Patton headed east. The Third Army took off in a type of American blitzkrieg not seen since Union Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman’s rapid marches through Georgia and the Carolinas during the Civil War.

Throughout August 1944, Patton won back over the press. He was foul-mouthed and uncouth and led from the front in flamboyant style with a polished helmet and ivory-handled pistols.

In fact, his theatrics masked a deeply learned and analytical military mind. Patton sought to avoid casualties by encircling German armies. In innovative fashion, he partnered with American tactical air forces to cover his flanks as his armored columns raced around static German formations.

Naturally rambunctious American GIs fought best, Patton insisted, when “rolling” forward, especially in summertime. Only then, for a brief moment, might the clear skies facilitate overwhelming American air support. In August, his soldiers could camp outside, while his speeding tanks still had dry roads.

In just 30 days, Patton finished his sweep across France and neared Germany. The Third Army had exhausted its fuel supplies and ground to a halt near the border in early September.

Allied supplies had been redirected northward for the normally cautious Gen. Montgomery’s reckless Market Garden gambit. That proved a harebrained scheme to leapfrog over the bridges of the Rhine River that would devour Allied blood and treasure, and accomplish almost nothing in return.

Meanwhile, the cutoff of Patton’s supplies would prove disastrous. Scattered and fleeing German forces regrouped. Their resistance stiffened as the weather grew worse and as shortened supply lines began to favor the defense.

Historians still argue over Patton’s August miracle. Could a racing Third Army really have burst into Germany so far ahead of Allied lines? Could the Allies ever have adequately supplied Patton’s charging columns given the growing distance from the Normandy ports? How could a commander like Eisenhower handle Patton, who at any given moment could let loose with politically incorrect bombast?

We do not know. Nor do we quite know the price that America paid for having a profane Patton stewing in exile for nearly a year rather than exercising his leadership in Italy or Normandy.

We only know that 70 years ago, an authentic American genius thought he could win the war in Europe — and almost did. When his Third Army stalled, so did the Allied effort. What lay ahead in winter were the Battle of the Bulge and the nightmare fighting of the Hürtgen Forest — followed by a half-year slog into Germany.

Patton would die tragically from injuries sustained in a freak car accident not long after the German surrender. He soon became the stuff of legend, but was too often remembered for his theatrics rather than his authentic genius that saved thousands of American lives.

Seventy years ago this August, George S. Patton showed America how a democracy’s conscripted soldiers could arise out of nowhere to beat the deadly professionals of an authoritarian regime at their own game.”

_________________________________

Patton’s characteristic brashness and simplification of all matters to strategic imperatives is not acceptable in today’s parlance. But his conclusions in his Diary while abjectly “politically incorrect” have a military sensibility:

The difficulty in understanding the Russian is that we do not take cognizance of the fact that he is not a European but and Asiatic and therefore thinks deviously. We can no more understand a Russian than a Chinaman or a Japanese and, from what I have seen of them, I have no particular desire to understand them except to ascertain how much lead or iron it takes to kill them. In addition to his other amiable characteristics, the Russian has no regard for human life and is an all out son of a bitch, a barbarian, and a chronic drunk.

I certainly do not agree with the gross simplification, but Patton’s instinct to recognize a threat and respond with overwhelming force to eliminate that threat is a warrior’s skill.

Churchill shared Patton’s concern about Russia and ordered plans for the invasion of Russia with a hypothetical commencement on July 1, 1945: “Operation Unthinkable” should have been given more sober thought and Patton’s Third Army greater license and more supplies.

_________________________________

Additional Links: