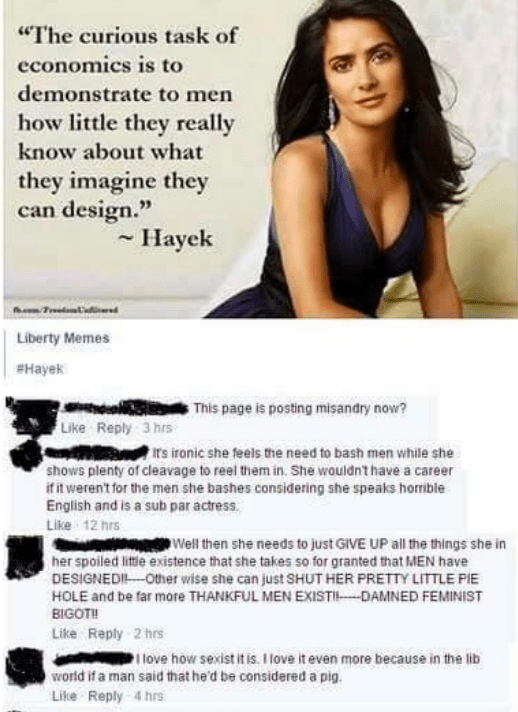

Had to memorialize this gem of a thread:

Elizabeth Cohen was clearly baiting the idiots – and she reeled them in (and protected their identities). It was a cheap shot designed to draw trolls, but cheap shots are great tactics in combat. This wasn’t “the wisdom of crowds.” It was the illiteracy of crowds: a failure of basic attribution, context, and reading that proves how quickly online herds smuggle their priors into any fragment of text.

That little pile-on is the modern parable. We live inside an attention economy where pattern-matching replaces comprehension. See a name, infer a villain, invent a grievance. In miniature, it shows why technocratic dreams fail at scale: if a swarm can’t parse a byline, how will planners parse a civilization?

_______________________

F.A. Hayek remains underappreciated. The vast majority of American universities – and I suspect most European also – remain under the hex of Marxism. By that, I do not mean the professional economists, rather the literary departments and social scientists who continue to bemoan Utopian delusions and power-dynamic pandering without ever having lived more than their myopic experience which they consider the only verity.

Although the Marxist-mind professes atheism, it remains devoutly deist in its thinking: it believes in omniscient design, merely replacing God with the Planner. As Hayek wrote in The Counter-Revolution of Science, “The rationalist cannot conceive of a self-organizing order; he must imagine an orderer.” That is the heresy of our intellectual age, the belief that complexity requires control.

Hayek diagnosed it perfectly in The Fatal Conceit:

The curious task of economics is to demonstrate to men how little they really know about what they imagine they can design. To the naive mind that can conceive of order only as the product of deliberate arrangement, it may seem absurd that in complex conditions order, and adaptation to the unknown, can be achieved more effectively by decentralizing decisions and that a division of authority will actually extend the possibility of overall order. Yet that decentralization actually leads to more information being taken into account.

― Friedrich Hayek, The Fatal Conceit: The Errors of Socialism [1]

Hayek is the better humanist precisely because he loves mankind as it is, not as it might be under perfect supervision. Marx could never do that. His followers persist because people will always crave two comforts: someone to blame and someone to save them. Marx promises both and deludes the vain into thinking they belong among the saviors.

Hubris!

And yet, how sweet the belief that you can redeem the world. “From each according to his abilities, to each according to his needs.” What could sound fairer, or prove more ruinous?

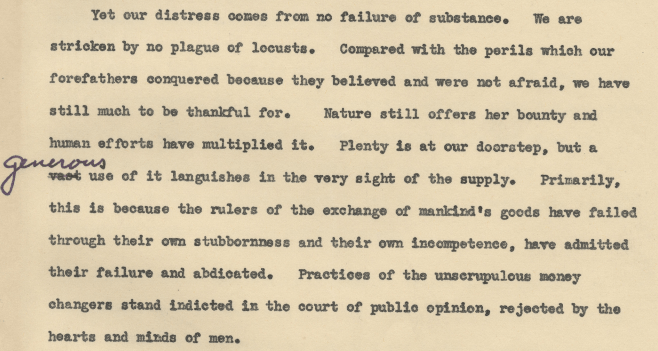

Historians laud F.D.R. as if he were the savior of the economy rather than an exacerbating factor perpetuating the Great Depression. Roosevelt’s 1933 inaugural address with its silly perils of plentitude constrained by the lords of the supply chain:

“Plenty is at our doorstep, but a generous use of it languishes in the very sight of supply. Primarily, this is because the rulers of the exchange of mankind’s goods have failed through their own stubbornness and their own incompetence, have admitted their failure and abdicated.”

Pretty language masking the weakness of the argument and disguising its moral vanity. F.D.R. teases the listener, there is plenty for all, it’s just those incompetent men who have kept you all from it, and from working. All you need is before you, your new savior who will cast the money changers from the temple, give you all jobs and distribute the bounty. The imagery is Biblical, the economics is abysmal.

The true architect of this folly was Rexford Guy Tugwell, the administration’s self-anointed economic philosopher. As Under-Secretary of Agriculture, Tugwell authored the Agricultural Adjustment Act, paying farmers to destroy crops while the unemployed starved—a grotesque ritual of “planned scarcity.” He dreamed of relocating populations into government-designed “Greenbelt Towns” where production, consumption, and virtue would all be supervised by his enlightened hand.

Whence such confidence? In 1934 Tugwell visited Italy and in his Diary recorded that Mussolini’s regime is “doing many of the things which seem to me necessary [to create] the cleanest, neatest, most efficiently operating piece of social machinery I’ve ever seen. It makes me envious.” It was not hyperbole. Tugwell truly believed economies could be “scientifically” administered partnerships between government and cartels to moderate supply, fix wages, and restrain competition. He admired fascism’s administrative clarity and was blind to its moral cost.

The result was predictable: stagnation disguised as salvation. Fortunately, the Supreme Court struck down the National Recovery Administration and the AAA in Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States (1935) and United States v. Butler (1936). Rothbard would later write that Hoover and Roosevelt shared “the same faith in managerial coercion, differing only in tempo.” Tugwell was that faith’s evangelist.

He soon departed Washington to become, ignominiously, the last appointed Governor of Puerto Rico, a fitting exile for a man who sought to govern everything.

Central planning’s corpse was briefly reanimated by the exigencies of World War II. Governments that had failed to cure depression by decree mistook the forced mobilization of war production for proof of “planning efficiency.” The Allies won not because of planning genius but because of resource scale and industrial endurance. Yet the illusion endured.

Post-war idealists, mistaking wartime compulsion for peacetime coordination, built social democracies whose apparent success rested on two unacknowledged subsidies: American military protection and demographic abundance. The U.S. peace guarantee allowed Europe to spend 3% or less of GDP on defense while funding expansive welfare states. That peace dividend is now spent. As Europe re-arms and ages, the accounting error becomes visible: central planning always consumes the future to fund the present. Tocqueville foresaw that democratic peoples, weary of uncertainty, would trade freedom for managed comfort: an exchange Tugwell mistook for progress.

Hayek posed the only question that matters: Who plans for whom? As he warned in The Road to Serfdom (see Privacy), “The more the state ‘plans,’ the more difficult planning becomes for the individual.”

The appeal of planning is metaphysical: it satisfies the craving for certainty in a world that resists design. Tugwell’s arrogance was the theological expression of that craving—economic Intelligent Design. Hayek saw that the very complexity of society made such omniscience impossible. Knowledge is dispersed, tacit, and adaptive; attempts to centralize it destroy the information they seek to harness.

____________________

[1] Hayek’s teacher Ludwig Von Mises published his devastating critique of the impossibility of the socialist calculation in 1920. Alex Tabarrok points to the most recent example in his post on the Infant Formula shortage.

____________________

Confessional Post-Script

Until reading Hayek’s Fatal Conceit, I too believed, arrogantly, that the premise of socialism was viable (I read George Bernard Shaw). I imagined myself among the philosopher-kings of Plato, an enlightened dictator in the mold of Augustus or Marcus Aurelius, armed with data instead of legions. I sympathized with Khan Noonien Singh and believed intelligence could substitute for humility.

I mistook intelligence for benevolence—the oldest sin of the planner. Even Hayek began as a Fabian sympathizer before Mises cured him of that conceit.

I have since come to see that the dream of perfectibility is the most persistent narcotic of the social sciences. Marx, Weber, Mills, all intoxicated by the same promise: that “science” could re-engineer virtue. Hayek’s antidote was brutal honesty. He demonstrated that cooperation precedes comprehension; morality is not deduced, it is inherited. As Hume wrote, “The rules of morality are not the conclusions of our reason.”

Hayek saw that civilization itself is the long evolution of rules before reasons, that “learning how to behave is more the source than the result of insight.” Tradition, imitation, and competition are the true engines of progress. His 1968 lecture “Competition as a Discovery Procedure” made the point explicit: competition is not equilibrium—it is experiment.

Hayek takes as demonstrably axiomatic that mankind is cooperative, therefore there never was a Hobbesian “war of all against all.” The rules of cooperation dictated the formation of a larger social arrangement and by necessity were restraints on individual behavior.

Liberty or Freedom is not, as the origin of the name may seem to imply, an exemption from all restraints, but rather the most effectual applications of every just restraint to all members of a free society whether they be magistrates or subjects.

Adam Ferguson

Language itself, he notes, is a spontaneously ordered system, propagated not by decree but by imitation. So too law, trade, and custom: emergent, adaptive, antifragile.

The origins of property and liberty, he reminds us, are twins. Strabo records (Strabo 10,4,16) that ancient Crete held “liberty as the state’s highest good and therefore made property belong specifically to those who acquire it.”

In contrast, the Spartans (proto-communists) abolished property, sanctified theft, and stagnated into extinction. Even Plato and Aristotle romanticized that static order, craving what Hayek called “a micro-order determined by the overview of omniscient authority.”

“Nothing is more misleading,” Hayek wrote, “than the conventional formulae of historians who represent the achievement of a powerful state as the culmination of cultural evolution: it has as often marked its end.”

Trade and free association, not decree, have driven civilization’s expansion. From xenia to the free ports of Athens and Amsterdam, spontaneous cooperation multiplied prosperity.

We are fish in water, blind to the medium that sustains us. Aristotle, blind to the complexity of the market, sneered at commerce as chrematistikē and idealized autarky, the self-sufficiency of philosophers living on slaves. It is the same arrogance that animates our modern Tugwells: the comfort of command without the burden of comprehension.

The planner’s dream is eternal because it flatters the intellect. But Hayek, and Rothbard after him, showed that intelligence without humility is tyranny in embryo. Every Tugwell is a Mussolini in waiting, certain that he can outthink the chaos of freedom.

Who plans for whom?

No one can plan for all. The market, messy, human, improvisational, is the only moral order precisely because it has no master. Cave ordinatorem, Beware the planner!

One thought on “Friedrich Hayek”