The ghost of Christmas past haunts us. Most of the Christmas traditions we Americans cherish are refinements and reinventions of the late Victorian era: Christmas trees, stockings and carols didn’t much exist before the 1840s. They were formalized during the reign of Queen Victoria, who, with Prince Albert, popularized the decorated evergreen and the domestic hearth as symbols of middle-class virtue.

If one digs a little farther back to the late 1700s (the reign of King George), we see that our ancestors showed more pluck and grit, as documented by their holiday party games.

Original text link >HERE< Source material derived from William Hone’s The Every-Day Book and Table Book (1825–27) and Robert Chambers’s Book of Days (1863).

Don’t try these at the company party in this snowflake era!

Snapdragon

Snapdragon traditionally was played Christmas Eve using a large, shallow bowl containing raisins. The raisins were then flooded with a bottle of brandy causing them to bob up and down. The brandy was then set ablaze.

Players would reach into the bowl to attempt to pluck a raisin from the flames and, if successful, pop it into their mouth. The real holiday joy was watching those players who were not so skilled. As one contemporary wrote, the game “provided a considerable amount of laughter and merriment at the expense of the unsuccessful competitors.” Scalding and second-degree burns – jolly good fun that!

Blind Man’s Bluff

You may remember playing a version as a child, but our ancestors were more rough and tumble when playing tag blindfolded.

In the earlier variation of the game, “it is lawful to set any thing in the way for Folks to tumble over, whether it be to break Arms, Legs or Heads, ‘tis no matter, for Neck-or-nothing, the Devil loves no Cripples.” Injuries were numerous enough that it was suspected that the game had been invented by “Country Bone Setters” as a way of ensuring business.

This satire appeared in early eighteenth-century jest books, notably Ned Ward’s London Spy (1703), and was likely exaggerated for comic effect. The suspicion is augmented with the even more salacious detail that some travelling surgeons would send “two or three pickled Whores of Figure to Pox the Parish both very necessary steps towards gaining good Business.”

Such bawdy moralism reflects the Georgian appetite for parodying both vice and virtue—what historian Peter Burke calls the “carnival of inversion” that temporarily suspended social order (Popular Culture in Early Modern Europe, 1978).

Questions and Commands

The predecessor of of today’s Truth or Dare, was also played on Christmas Eve, and had stiffer penalties. Failure to follow a command or answer a question led to a monetary fine, or getting your face blackened with soot from the fire. Questions and Commands was a drinking event with holiday appropriate strong ale flavored with nutmeg and sugar.

In an age before sentimental domesticity, such games reaffirmed community through shared risk and ridicule, what Victor Turner later theorized as communitas, the social leveling that arises through ritualized disorder (The Ritual Process, 1969).

Hoop and Hide

Hide and seek meets spin the bottle –

“As for the Game of Hoop and Hide, the Parties have the Liberty of hiding where they will, in any Part of the House and if it is prove to be in a Bed, and if they even then happen to be caught, the Dispute ends in Kissing, &c.”

The prurient behavior only added to the celebration of the holidays. Just plain ruddy fun.

Of course, class distinctions were more evident then – exhibited by dress, manners, and accent – but the gentry were expected to provide hospitality:

And there were obligations, noblesse oblige, and penalties for breaking custom: “I must also take notice to the stingy Tribe, that if they don’t at least make their Tenants or Tradesmen drink when they come to see them in the Christmas Holidays, they have Liberty of pissing behind the Door, which is a Law of very ancient Date.”

This marked the reciprocal economy of festivity: generosity from above, license from below. A reminder that charity was once enforced through ridicule, not virtue signaling.

Ghost Stories

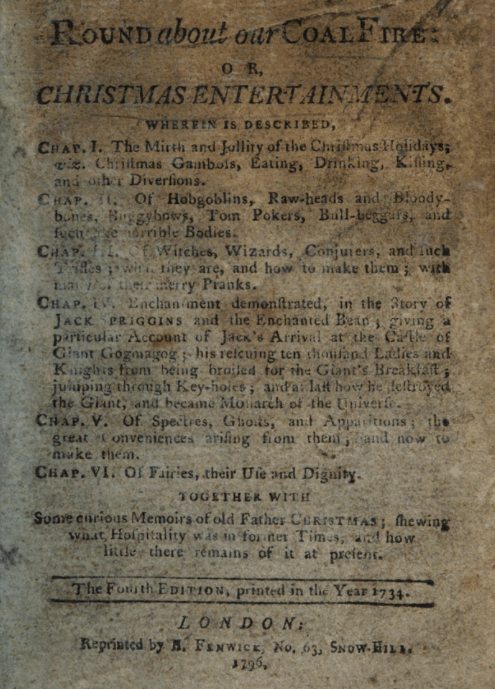

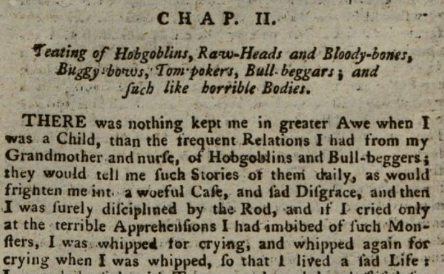

In addition to games, storytelling was cherished event, but the Georgians told stories of horror.

Wonderful chapter heading – telling stories of Hobgoblins, Raw-Heads and Bloody-bones… a ghost story at Christmas! (And hush little baby, don’t you cry, or mommy will whack you upside the head with a rod.)

Tim Burton had it kinda right, it seems.

Jack wants to forego his Halloween responsibilities of scaring and spread holiday cheer, but he was harkening to an earlier time when tales of ghosts, witches, and fairies were the norm. Christmas Eve was for tales of supernatural mischief. Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol is the vestigial story in the tradition of “winter tales” dating back at least as far as Shakespeare’s A Winter’s Tale, which is suffused with magic, madness and strange transformations. More modern presentations simplify the plot with action: Die Hard (1988), Reindeer Games (2000), and the forthcoming Violent Night (2022).

The conflation of horror and holiday cheer, like the mingling of Saturnalian revelry and Christian solemnity, a deep and continuing connection that we should be mindful of.

Happy Holidays!

_______________________

Academic Reflection

Eric Hobsbawm’s classic essay, The Invention of Tradition (1983), offers the perfect lens for this phenomenon. He argued that modern societies, seeking stability amid industrial and political upheaval, fabricate continuity by codifying rituals that appear ancient but are, in fact, recent consolidations of identity. The Victorian Christmas, with its domestic hearth, sentimental morality, and sanitized carols, was one such invention, repackaging the chaotic and corporeal energies of Georgian festivity into bourgeois virtue.

What the Victorians tamed, we inherited. The drunkenness, bawdiness, and spectral storytelling of earlier centuries gave way to a moralized nostalgia that still haunts our commercial Christmas. Even our most sacred symbols, a tree lit with electric candles, a feast framed by charity, are, in Hobsbawm’s phrase, “rituals of reassurance.”