Putin’s invasion of Ukraine is profoundly troubling me. While I am gladdened to see Western Europe galvanized against Russia and unified in economic sanctions, I still worry that it will not be sufficient. I worry that we could be witnessing a resurging war of ideology. Numerous intelligent scholars are dissecting Putin’s motives, but the fundamental question will remain, how does a society produce, and then submit to, such a man?

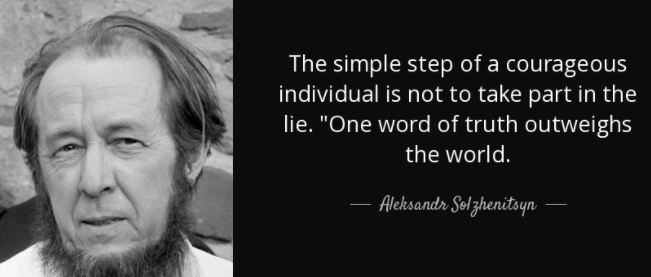

I have returned to Aleksandr Isaevich Solzhenitsyn for insights. The Gulag Archipelago is not read widely enough because it is not comforting; it shows the deep and truly demonic nature of collectivist beliefs and how the resulting “collectivism” garners power to a totalitarian leader.[1] Putin is just the latest incarnation of the system.

We have been here before.

But we have yet to escape the nightmare of a belief that beguiles so many idealists; that benevolence can be legislated and virtue administered. Idealists who both know better and whose lust for the improvement of all at any expense has only continued to lead to the death and destruction of more people than any other ideology in history.

When will we learn?

Igor Shafarevich is a poignant case. He was an early Soviet dissident and described why the collectivist vision was perniciously attractive in his essay, “Socialism in Our Past and Future.” His later book, The Socialist Phenomenon (1973), traced socialism’s roots from the Sumerian and Egyptian empires through to modern utopian movements, arguing that socialism is a recurring pathology and showed it as deadly in all its forms, especially Bolshevism. (And I contend that the current dialog on “equality” in America is nothing more than a poisonous variation on the socialist theme: legislated equality of outcome enforced through violence.)

Shafarevich died in 2017, in Moscow aged 93 and is a tragic figure to examine given Putin’s invasion. Shafarevich was born in Zhitomir, Ukraine, on June 3, 1923. He was a brilliant mathematician who had a demonstrated command of the problems of collectivism, but I fear his later writings will cast too dark a shadow on his earlier work. It is true that his essay, Russophobia (1982) reframed his critique of socialism into a defense of ethnic Russia, and asserted that Ukraine was “torn from the body of Russia” and that its port city of Sevastopol was “a key to the resurgence of Russia” ominously foreshadowing Putin’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 and all-out war in Ukraine in 2022.[2]

It is hard for me to reconcile his noble work as a dissident in the early 1970s with the subsequent turn to nationalism. I would have assumed a man who saw so clearly the danger of collectivism and who was an early member of the Committee on Human Rights, which was co-founded by Sakharov and whose membership included the author Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn would be better armed against the charm of nationalism. I assume that one would be inoculated since they are a disease of similar ideological failure.

The so-called West is not immune to these failures! Donald Trump is a populist ideologue of similar emotional grammar: grievance as doctrine, loyalty as truth, the crowd as creed. Trump is a frightening populist ideologue who exhibits none of the beliefs upon which the West was built.

The common danger here is ideological. All too often these ideologies are contrasted against and offered as a “cure” for systems of economic arrangement (the free market) and the compendium of laws (defining private property) that define Western culture. Marx was eloquent in his confusion, and his writings still befuddle many. Namely the many who think they know The way to arrange and plan human destiny.[3]

A belief in the necessity of the rule of law, the natural right to self-determination, free association, and freedom of commerce is not an ideology; the only known system by which diverse people can associate peacefully and prosperously. Everything else would be coercive. I suppose one could counter that the belief in the freedom of the individual is an ideological stance and not the natural state of man – for what is the natural state of man if not within a collective? – but that is, I contend, the very difference between the West and everywhere (and everywhen) else.

I once framed this mythologically, but historian Stephen Kotkin does so with more clarity and historical precision in this superb interview in The New Yorker (March 11, 2022). Kotkin’s defense of the West, I hope, reminds those “woke” ideologs who scream the evils of capitalism, calls them back to its virtues.

The Weakness of the Despot

An expert on Stalin discusses Putin, Russia, and the West.

How do you define “the West”?

The West is a series of institutions and values. The West is not a geographical place. Russia is European, but not Western. Japan is Western, but not European. “Western” means rule of law, democracy, private property, open markets, respect for the individual, diversity, pluralism of opinion, and all the other freedoms that we enjoy, which we sometimes take for granted. We sometimes forget where they came from. But that’s what the West is.

…And yet, as corrupt as China is, they’ve lifted tens of millions of people out of extreme poverty. Education levels are rising. The Chinese leaders credit themselves with enormous achievements.

Who did that? Did the Chinese regime do that? Or Chinese society? Let’s be careful not to allow the Chinese Communists to expropriate, as it were, the hard labor, the entrepreneurialism, the dynamism of millions and millions of people in that society.

On a kind of natural resource curse (Venezuela?) :

…in Russia, wealth comes right up out of the ground! The problem for authoritarian regimes is not economic growth. The problem is how to pay the patronage for their élites, how to keep the élites loyal, especially the security services and the upper levels of the officer corps. If money just gushes out of the ground in the form of hydrocarbons or diamonds or other minerals, the oppressors can emancipate themselves from the oppressed. The oppressors can say, we don’t need you. We don’t need your taxes. We don’t need you to vote. We don’t rely on you for anything, because we have oil and gas, palladium and titanium.

On why the stupid get on top in totalitarian arrangements:

You have to remember that these regimes practice something called “negative selection.” [In a democracy] You’re going to promote people to be editors, and you’re going to hire writers, because they’re talented; you’re not afraid if they’re geniuses. But, in an authoritarian regime, that’s not what they do. They hire people who are a little bit, as they say in Russian, tupoi, not very bright. They hire them precisely because they won’t be too competent, too clever, to organize a coup against them. Putin surrounds himself with people who are maybe not the sharpest tools in the drawer on purpose.

That does two things. It enables him to feel more secure, through all his paranoia, that they’re not clever enough to take him down. But it also diminishes the power of the Russian state because you have a construction foreman who’s the defense minister [Sergei Shoigu], and he was feeding Putin all sorts of nonsense about what they were going to do in Ukraine. Negative selection does protect the leader, but it also undermines his regime.

On the importance of error correction:

…Finally, you’ve given credit to the Biden Administration for reading out its intelligence about the coming invasion, for sanctions, and for a kind of mature response to what’s happening. What have they gotten wrong?

They’ve done much better than we anticipated based upon what we saw in Afghanistan and the botched run-up on the deal to sell nuclear submarines to the Australians. They’ve learned from their mistakes. That’s the thing about the United States. We have corrective mechanisms. We can learn from our mistakes. We have a political system that punishes mistakes. We have strong institutions. We have a powerful society, a powerful and free media. Administrations that perform badly can learn and get better, which is not the case in Russia or in China. It’s an advantage that we can’t forget.

I encourage you to read the whole thing.

I can only hope that there are numerous Petrovs who remain humanely human within the Russian cadre who can act as a correction mechanism for despotic insanity.

_______________

[1] In this regard, I link Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn with Friedrich Hayek: where Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom (1944) demonstrated theoretically that collectivist planning leads inexorably to totalitarianism, Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago (1973) provides the lived and literary evidence of that descent. Together, they form an empirical and moral continuum. Hayek diagnosed the disease, Solzhenitsyn survived it.

[2] March 15, 2022 – Timothy Snyder on the Myths That Blinded the West to Putin’s Plans, The New York Times – a conversation with historian Timothy Snyder, interviewed by Ezra Klein:

EZRA KLEIN: Something you’ve said in different venues is that Putin’s essays, speeches about Ukraine are less revealing about the nature of Ukraine than they are about the nature of Russia. You wrote, “what is most striking about Putin’s essay is the underlying uncertainty about Russian identity. When you claim that your neighbors are your brothers, you are having an identity crisis.” Can you talk a bit about what’s being revealed, or for that matter, confused here about Russian identity?

TIM SNYDER: I think Russian national identity is extremely confused and you can understand the need for Ukraine as a kind of shortcut, as a kind of way of resolving all these problems. Because you can say, well, I mean, this is a kind of dumb analogy, but you can say, well, the only problem with my life is I don’t have somebody else, you know? But anybody who says that is probably incorrect. And what Putin is saying — if we kind of reduce all the philosophical stuff down to a very simple proposition, he’s saying, Russia is not itself without Ukraine.

But if you’re not capable of being yourself without attacking and absorbing, violently, someone else, some other country, the real question might be about you, the real question might be about how you see the world, how you’re living in the world. So I think there’s a serious problem with Russian national identity.

[3] Plato’s Republic began the Western habit of mistaking political design for philosophical salvation. His philosopher-king was to guide the collective; a benevolent autocrat whose reason would redeem the polis. Of course, Plato was writing in the shadow of Athens’ defeat by Sparta in 404 BCE; his was a practical goal: how does Athens best Sparta? The answer he offered was to re-engineer Athens into a moralized Sparta, a city ruled by guardians and directed by reason rather than commerce. As Karl Popper later argued in The Open Society and Its Enemies (1945), Plato’s blueprint for order became the template for every subsequent utopian tyrant who believed he could legislate virtue into existence. All the reforms Plato suggested were Spartan institutions disguised as philosophy.