Arnold Toynbee’s A Study of History is a 12-volume monster. I have read only the two-volume abridgement (many years past), which preserves Toynbee’s central thesis that there is a pattern to history. Civilizations rise and fall primarily in response to specific challenges; whatever those challenges are will be defining, and they must also be of the right pressure. For Toynbee, the vitality of a civilization depends on whether its “creative minority” can respond creatively to those pressures: excessive challenges cause collapse, and insufficient ones lead to stagnation.

Toynbee is (I suspect) not read much because he also subscribes to a version of the “great man” theory, wherein growth (historical progress) is attributable to a select group of identifiable creative minorities—those elite individuals who inspire and lead the masses. (It is of course apostate to think that white men may have played a positive role in history, and worse to think of any of them as great.)

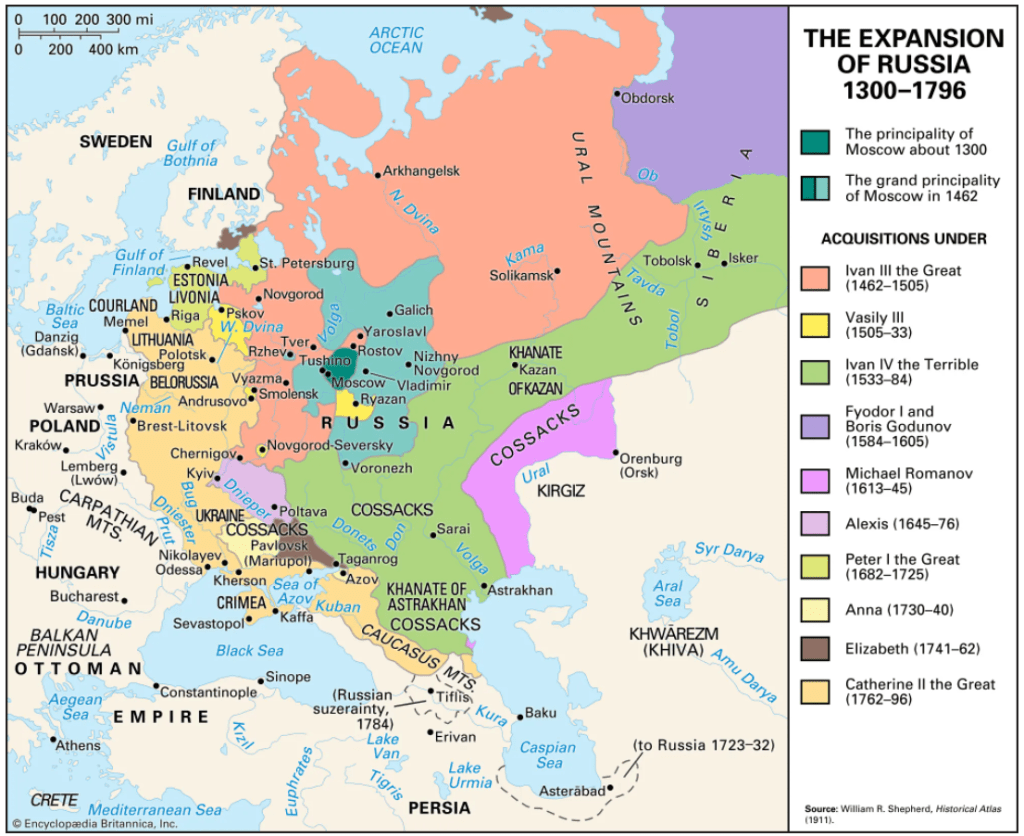

Nevertheless, Pyotr Alekséyevich is still known as “Peter the Great” because he began to modernize Russia—which meant to mimic Europe. He forced the nobles to shave their beards, adopt European dress, introduced Western education, and built St Petersburg on the Gulf of Finland to open Russia to Europe (Hosking, Russia and the Russians, 2001, pp. 166-175). He also reformed the military, founded a navy, restructured administration, and expelled Sweden from the Baltic coast to access ice-free waters (Massie, Peter the Great: His Life and World, 1980).

Under Empresses Elizabeth (1741-61) and Catherine the Great (1762-96), this centralization continued. They expanded the empire, taking territory from the Ottomans, Poland-Lithuania, and the Crimean Khanate (Riasanovsky & Steinberg, A History of Russia, 8th ed., 2011, pp. 243-258).

It wasn’t until Tsar Alexander I (1801-25) that Russia was challenged by Europe itself, specifically Napoleon’s ill-fated invasion. That trauma hardened a barrier mentality among the leadership of Russia. Alexander sought to create an international order to contain revolutionary contagion; his son, Tsar Nicholas I (1825-55) made stamping out revolution in Europe to protect Russia from corrupting foreign influences a mission.

Niall Ferguson reminded us in his January 2022 article (written just before the invasion of Ukraine) that Putin’s early demands were entirely consistent with this history: buffer zones, sacrosanct borders, deference to Russian “security needs.” A hundred days later, Russian armor rolled across those buffers. Putin was not innovating; he was reenacting. History, weaponized as ideology.

Orwell saw this coming:

Who controls the past, controls the future: who controls the present, controls the past… Past events, it is argued, have no objective existence, but survive only in written records and in human memories.

George Orwell, 1984

The problem with history as ideology is not just falsification but amnesia. Once the record becomes propaganda, moral agency disappears. Actions are no longer judged—they are explained away. For Putin, Finland is not a neighbor but a “modern construct,” and therefore fair game; Crimea “belongs” to Russia because the narrative requires it. That is the challenge of history as ideology: facts are de-contextualized and politicized, and become elusively arbitrary. Where does one start and stop the clock?

https://www.visualcapitalist.com/2400-years-of-european-history/

In 1939, Toynbee wrote,

The challenge of being called upon to create a political world-order, the framework for an economic world-order … now confronts our Modern Western society.

A Study of History, vol. 5, The Disintegrations of Civilizations (Oxford University Press, 1939)

World War II nearly met that challenge. The antagonists were destroyed, the British Empire exhausted, America ascendant. The Cold War that followed defined my youth: two empires, each claiming universal truth. But Russia’s might proved to be a Potemkin façade; a show of strength concealing demographic, industrial, and moral decay. Ukraine has made that decay visible again.

Enter Noam Chomsky. A good man, yes, but an idealist—and therefore a poor realist. His linguistics sought Platonic forms, deep structures beneath speech; his politics suffer the same blindness. Chomsky assumes that human nature can be reasoned into decency. Like Plato, he mistakes insight for control. Aristotle, observing rather than imagining, would have recognized the error.

Chomsky misjudges Putin’s war because he believes diplomacy, once articulated, retains normative force in the face of raw ambition. He treats James Baker’s supposed “no NATO expansion” remark as sacred covenant rather than diplomatic vapor (track his positions in truthout). Silly Chomsky. He fails to understand ambition as a moral category. Evil does not honor agreements; it exploits them. Chamberlain learned that lesson at Munich.

Chomsky’s logic is that a woman should not wear revealing clothing if she doesn’t want to be raped; Ukraine should not have courted NATO if it didn’t want to be invaded. It is the language of blame disguised as reason.

He argues further that “the West is fighting Russia to the last Ukrainian,” a line that sounds profound only until you recall that Ukrainians are not proxies but participants. They are fighting for home and hearth; the Russians for a phantom empire sustained by propaganda and fear. Chomsky’s pacifism mistakes blood for failure, as though moral clarity were best achieved without cost. He forgets that some ideas can only be defeated with an explosive drone (Moyn, Humane: How the United States Abandoned Peace and Reinvented War, 2021, pp. 404-410).

Yes, this war will likely end in negotiation; wars always do. But moral agency lies in the terms of that negotiation. Ukraine cannot yield simply because others are tired of watching. Aggression by totalitarian regimes must be resisted precisely because it is moral to do so.

Toynbee would have recognized this moment. Civilizations do not fall when they are defeated; they fall when their creative minorities lose the courage to act. Chomsky’s paralysis is that of a civilization too comfortable to remember what courage feels like. He confuses commentary with contribution

Thus, he is perfectly comfortable moralizing a solution, a new world order predicated on the fantasy of perfect restitution. Whether it is Putin’s imperial nostalgia or America’s confessional politics of reparations, he imagines that justice can be managed into existence by reason itself. It cannot.

Why not? Because the clock of history has no neutral hand. When does one stop the historical clock of restitution? No surprise the answer depends upon whose goals are being prioritized.