The proliferation of wearable technology to grab biometric information should prove beneficial, if it is allowed to do so:

Wearable technology promises to revolutionise health care

Do not let bureaucracy delay matters

The Economist, May 5, 2022

I am optimistic for the future of health care when technology allows for the treatment of individuals and not the theoretical, average human. Because of how drug trials must be conducted on sample groups, most drugs work in just 30-50% of patients. There is a promise that individual regimes are more effective than the one-size-fits-all kind. When doctors can see into a patient’s body in real time all the time, they can provide better care or even respond in remotely (defibrillators).[1]

I prefer to wear mechanical watches (sorry Apple), so I purchased an Oura ring to start tracking my data (Covid-inspired hypochondria?).

The Oura ring fitbits my activity level and delves my sleep cycle. It gives me all the variables; total hours asleep, REM time, deep sleep, body temperature, etc., more data than I know how to use. The data show me two primary conclusions about my sleep habits, (1) alcohol really does impair sleep health and (2) I never get sufficient deep sleep. The ring app reassures me that the amount of deep sleep erodes with age, but I suspect I should really get more – and despite the data the ring provides, I haven’t been able to improve my numbers.

Medical websites extol the importance of sleep and assure me (as does my ring) that good sleep is critical to maintaining good health. But then I remembered the odd Victorian habit of “second sleep.”

The myth of the eight-hour sleep

BBC, February 22, 2012

Prof. Roger Ekirch’s At Day’s Close (2006), is the definitive study on historical sleep habits. His work shows that during the pre-industrial era, people slept in two installments (biphasic sleep). He argues that from time immemorial to the nineteenth century, the dominant pattern of sleep in Western societies was biphasic, when most individuals retired between 9 and 10 pm, slept for three to four hours during their “first sleep,” awakened after midnight for an hour or so, during which individuals conducted normal “daytime” activities before taking a “second sleep,” roughly until dawn. As electric lights came into widespread use and illuminated the night, this pattern changed. People now worked and recreated even after the sun retired because of artificial light and therefore went to sleep much later, resulting in the “new normal” – sleeping in a continued stretch till morning. (Craig Koslofsky’s Evening’s Empire (2011) is also recommended.) Ekrich finds evidence of biphasic sleep in the Odyssey, Aeneid, Thucydides and Livy. (Time to re-read them with a more discerning eye!)

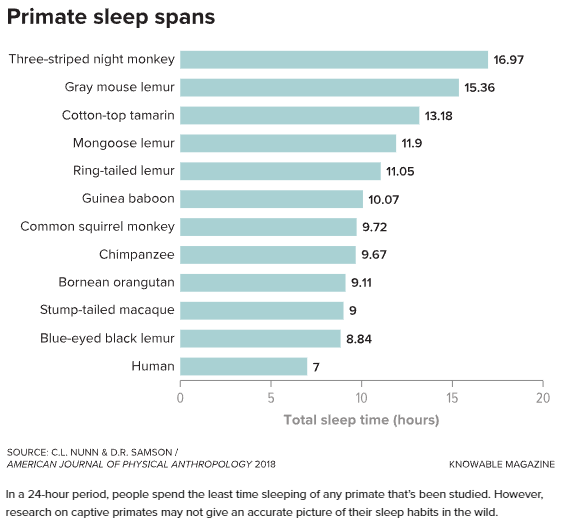

Controlled studies and ethnographic evidence suggest that biphasic sleep is the norm for humans in an environment without artificial light. From a physiological perspective, sleep is vital for regenerative health and optimal physical and cognitive performance. Evolutionarily then, the “natural” human sleep pattern is paradoxical. Humans sleep the least of all primates. And despite the advantages of monolithic sleep, comparative data sets from small-scale societies show that the phasing of the human pattern of sleep–wake activity is highly variable and characterized by significant nighttime activity. To reconcile these phenomena David Samson (2021) postulated the social sleep hypothesis wherein he proposes that extant traits of human sleep emerged because of social and technological niche construction. Specifically, as early humans started sleeping on the ground (terrestrially) rather than in the relative safety of trees, they were subject to more predatory threats. The biological adaptation was to shorten the cycle but increase the quality (more REM sleep). “Short, highquality, and flexibly timed sleep likely originated as a response to predation risks [and] may have been a necessary preadaptation for migration out of Africa and for survival in ecological niches that penetrate latitudes with the greatest seasonal variation in light and temperature on the planet.”

As a species, regardless of how we accomplish it, the total amount of sleep humans get on average isn’t very much.

Samson’s work expands upon that of Isabella Capellini, et alia, their 2008 publication – with the insomnia curing title, Phylogenetic Analysis of the Ecology and Evolution of Mammalian Sleep, wherein they conclude:

In terms of predation risk, both REM and NREM sleep quotas are reduced when animals sleep in more exposed sites, whereas species that sleep socially sleep less. Together with the fact that REM and NREM sleep quotas correlate strongly with each other, these results suggest that variation in sleep primarily reflects ecological constraints acting on total sleep time, rather than the independent responses of each sleep state to specific selection pressures. We propose that, within this ecological framework, interspecific variation in sleep duration might be compensated by variation in the physiological intensity of sleep.

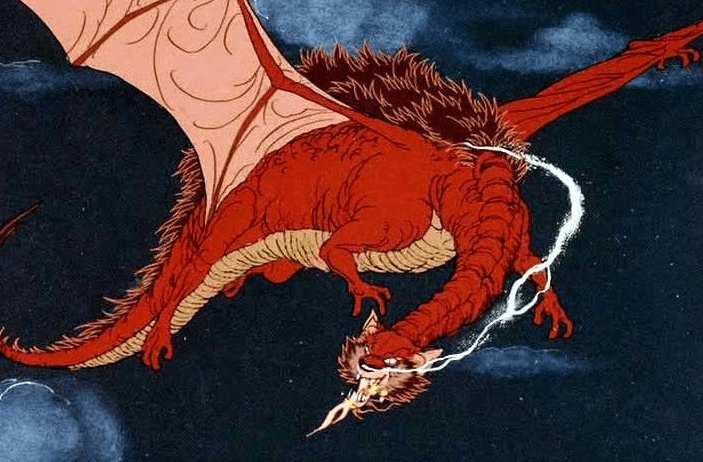

The evolutionary impact on human sleep patterns is intriguing to me. I recall Jordan Peterson commenting on the perdurable image of a dragon. Dragons incorporate the most powerful aspects of those animals that predated on our primordial ancestors: birds of prey, snakes, and feral cats.

In his talk, Peterson forgot the name of scholar who postulated the theory, but the reference is to An Instinct For Dragons (2002) by David Jones. His basic premise is that millions of years ago, our ancestors lived and slept in trees. The relative safety of trees limited predation to birds of prey. As our ancestors transitioned out of the trees to live on the ground, the pool of predators increased to include snakes and lions. Jones’s work also uses the widespread fossil records may also have incited the fear of large reptilian threats (on that see Adrienne Mayor’s work, specifically Flying Snakes and Griffin Claws, and Other Classical Myths, Historical Oddities, and Scientific Curiosities. Princeton University Press, 2022).

Increased threats leading to shorter and communal sleep patterns as a survival strategy is obvious to warriors who divide darkness into watches:

Old English wæccan “keep watch, be awake,” from Proto-Germanic *wakjan, from PIE root *weg- “to be strong, be lively.” Essentially the same word as Old English wacian “be or remain awake” (see wake (v.)); perhaps a Northumbrian form of it. Meaning “be vigilant” is from c. 1200. That of “to guard (someone or some place), stand guard” is late 14c. Sense of “to observe, keep under observance” is mid-15c. Related: Watched; watching

The Hebrews divided the night into three watches, the Greeks usually into four (sometimes five), the Romans (followed by the Jews in New Testament times) into four.

Oxford English Dictionary

Good sleep defined as surviving the night –

_________________________

The leading image is from Goya’s “The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters” (El sueño de la razon produce monstruos) circa 1797. It was one in a series of prints, Los Caprichos (whims, follies), published in 1799 as a condemnation of the foolishness in the Spanish society in which he lived. We need another Francisco Goya to depict the foolishness all too prevalent in America today.

_________________________

[1] The wearable technology will quickly become implanted and powered by glucose powered electricity.

One thought on “Sleep”