My introduction to cosmology was Carl Sagan’s Cosmos: A Personal Voyage (1980). What struck me was Sagan’s cadence. He spoke slowly, almost reverently, as though the subject demanded awe before explanation. He framed knowledge as a moral duty: to understand our place, to cultivate humility in the face of immensity.

The series worked because it wasn’t trying to impress; it was trying to re-orient. Sagan gave you vertigo. He let you feel small, not as humiliation, but as invitation. When he said “We are made of star-stuff,” it connected you to the universe even as it grounded you. (Episode 9: “The Lives of the Stars.”)

Decades later, Neil deGrasse Tyson rebooted the series as Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey (2014). His version was polished, graphically dazzling, filled with modern astrophysics. It succeeded as education and spectacle, but the tone was different. Tyson plays the role of tour guide; Sagan, of priest. Tyson asserts; Sagan lingered. Tyson’s episodes march forward with the confidence of settled knowledge; Sagan’s haunted you with the possibility that we know almost nothing at all.

I prefer the original. Sagan’s Cosmos left viewers slightly unsettled, a little diminished, but more open. Tyson’s leaves them reassured, more certain, more comfortable in the grandeur. Both series educate, but only Sagan’s asks for reverence rather than applause.

That first vertigo of scale is what matters here. Sagan gave a child the sensation of falling upward into immensity, and that is the right beginning for any story of cosmology. Humanity has been falling upward for millennia: from Earth at the center, to the Sun, to the stars, to the Milky Way, and finally to galaxies beyond number. Each step felt destabilizing, then astonishing, and finally ordinary.

The arc of knowledge is not only scientific but cultural. When Copernicus displaced Earth, the shock lasted centuries. When Hubble displaced the Milky Way, the shock lasted decades. Now, the idea of parallel universes, the multiverse, shows up in movie scripts as if it were as trivial as a subway. What was once vertiginous is now mundane.

Humanity’s imagination has always chased the horizon of scale. Each age redraws the map of the universe, only to discover that what seemed boundless was a provincial neighborhood all along. We live in an era where blockbuster films toss around the word multiverse as though Niels Bohr moon-lighted in Hollywood. What was once scandalous is now mundane. The shock comes in looking backward: Einstein rewrote the structure of reality itself without even knowing that other galaxies existed.

That fact still floors me. His annus mirabilis (1905) preceded our very awareness of cosmic scale. Einstein derived relativity, time dilation, and the equivalence of mass and energy from a universe he believed was confined to a single island of stars. He bent the frame of the cosmos before he even knew how large the frame was.

For the Greeks, cosmos meant order. The universe was a dome of fixed stars, and the Milky Way was said to be Hera’s milk spilled across the heavens. Earth sat at the center. It was a conclusion drawn from naked-eye astronomy and from a deeper conviction that the heavens were made for human comprehension.

In 1543, Copernicus quietly pushed Earth off the pedestal, placing the Sun at the center. Galileo’s telescope a century later revealed the Milky Way as a street of stars, not a smear. The human estate shrank to a planet among others. Still, the “universe” ended at the edge of the Milky Way. Infinity was a word whispered by philosophers, not a scale felt in the bone.

Newton’s Principia (1687) stretched space to infinity and filled it with stars. But that was mathematics. For the common imagination, the sky remained a crystal sphere with the Milky Way as its border.

In 1838, Friedrich Bessel measured the parallax of 61 Cygni, 11 light years away. It was a small number by today’s standards, but it smashed the parochial cosmos. The Sun was one star among many, not the center of anything. By the late 19th century, school-books preached a universe of stars, but the word galaxy still meant only one: the Milky Way.

When Einstein imagined chasing a beam of light or an elevator in free fall, he believed he was describing the whole of reality and “reality” meant a single galaxy.

And yet, those thought experiments remain astonishingly fertile. The Pound-Rebka experiment (1959) confirmed gravitational redshift. Gravity Probe A (1976) tested time dilation in Earth’s orbit. Binary pulsars, measured to exquisite accuracy, orbit just as Einstein predicted. LIGO and Virgo’s detections of gravitational waves matched his field equations. And data from DESI show that cosmic structure over eleven billion years still conforms to Einstein’s theory of gravity (DESI Collaboration, 2024). Einstein’s imagination outran available instruments by decades, and it still sets the standard.

This is the marvel: reason can exceed observation. Einstein deduced the grammar of spacetime itself from logic, symmetry, and thought experiment. He was reasoning about infinity without ever knowing that the Milky Way was just one among billions.

In 1920 Harlow Shapley and Heber Curtis staged the “Great Debate” which asked, were the spiral nebulae part of the Milky Way or universes of their own? Four years later Hubble answered definitively: Andromeda was far outside our galaxy. By 1929, he showed space itself was stretching.

Einstein’s cosmological constant, his “blunder,” tried to mathematically hold the universe still. The irony is exquisite: the man who taught us that motion is relative tried to freeze the motion of stars.

By the 1930s newspapers spoke casually of “millions of galaxies.” Schoolchildren grew up in an expanding universe. What had been elite knowledge filtered into everyday speech within a single generation. The boundary of the cosmos leapt outward, and the public imagination stretched to meet it.

Now, a century later, films describe the multiverse as if it were trivial. The philosophical vertigo that once made scientists unnerved is served up as entertainment.

Here Professor David Kipping’s work on the “Cool Worlds” podcast restores the restraint that wonder requires. In episodes on Dyson spheres, habitable moons, and alien megastructures (Episode 252), Kipping insists that scientific speculation must remain anchored to evidence and bounded by ignorance. He reminds listeners that astronomy is a science of inference, not revelation; the cosmos remains mostly unknown, and that ignorance is not a flaw but a feature.

In that sense, Kipping extends Sagan’s ethos. Both men defend curiosity as an act of humility. They differ mainly in temperament: Sagan’s tone is liturgical, Kipping’s analytic. But the impulse is the same: to keep awe empirical.

Across these three voices, the gradient is clear: Sagan demanded reverence; Tyson offers confidence; Kipping warns against comfort. Each marks a different attitude toward the unknown: devotion, mastery, and restraint.

From the scientific realm, I wander toward its fictional mirror: Wolfe’s dying sun. Sagan’s cosmos is vibrant, expanding, alive with energy; Wolfe’s Urth is static and dim. Both describe the same existential horizon from opposite directions: the boundary where knowledge confronts finitude. Sagan sees dignity in exploring; Wolfe, in enduring.

Sagan taught that we are made of star-stuff. We are matter awakened to consciousness. Wolfe reminds us that even consciousness decays into myth. Sagan’s awe was secular but sacramental: reverence for reality itself. Wolfe’s awe is theological: redemption through entropy. One gazes outward in wonder; the other inward through shadow.

Between them flickers our imagination. The multiverse, once the frontier of philosophy, now serves as a cinematic trope. What Sagan offered as reverence for the unknown has been replaced by the comfort of endless possibility, a cosmos without consequence.

Here, Nietzsche’s question of the eternal return takes on new relevance: if every act recurs eternally, is it infinitely significant or infinitely trivial? Sagan’s would answer yes; the cycle of birth and death as cosmic affirmation. Wolfe’s might answer not yet; that redemption requires repetition until grace is learned. At first glance this sounds Buddhist, recurrence as purification, but his circle is not samsara. It is Augustinian, a salvation history in which time is redeemed through memory, not escaped through oblivion.

Augustine’s universe moves not in circles but in pilgrimage: creation, fall, and restoration unfolding toward consummation. In Wolfe’s dying Urth, Severian’s prodigious memory becomes the narrative instrument, but it is his choices, his acts of mercy and courage, that earn Zadkiel’s verdict and the world’s renewal. His is a pilgrim’s progress through moral trial. [1]

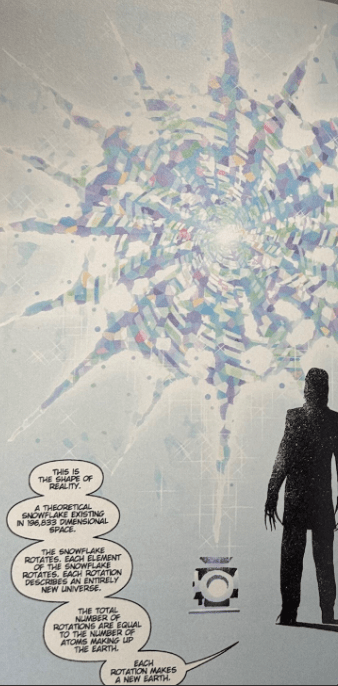

In Planetary (Ellis & Cassaday, 1999–2009), the multiverse is not discovered but computed: a machine cracks the cosmic code and summons its mirrored worlds. Each universe collides with its reflection, and the heroes’ revelation becomes a curse of endless recursion: a parable of modern cosmology, where infinity is treated as software and consequence as glitch.

Marvel takes this one step further. In Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022), reality is torn apart for sentimental cause. In Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021), every life saved fractures another world. These stories no longer ask whether humanity should open the door. It already has. The godlike act remains, but the responsibility is gone.

Wolfe restores gravity to the infinite. The circle closes not in extinction but in anamnesis, Augustine’s recovery of divine memory, the recollection of the light that first called creation into being. The New Sun is not another turn of the wheel but the restoration of radiance. Where Sagan’s cosmos invites awe through immensity, Wolfe’s invites reverence through remembrance. The rediscovery, at the end of time, of the grace that began it.

Nietzsche, in Thus Spoke Zarathustra, offered the bridge between them:

I say unto you: one must still have chaos in oneself to be able to give birth to a dancing star. I say unto you: you still have chaos in yourselves.

Sagan saw the dancing star as the universe awakening to itself; Wolfe saw it as the soul struggling toward a light it can no longer see. Planetary rendered it as calculation; Marvel franchised it into spectacle. Between them flickers our brief creative intelligence: the same spark that let Einstein pierce the veil. We remain, as Sagan said, star-stuff dreaming of its own return.

_____________________

[1] Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress and Wolfe’s Book of the New Sun trace parallel moral topographies separated by theology but united by form. Bunyan’s Christian journeys through allegorical landscapes that dramatize the Protestant conviction of unmediated grace: the pilgrim reads Scripture, feels conviction, and through faith alone finds the Wicket Gate. Salvation unfolds as a matter of inward illumination rather than institutional mediation. Wolfe, by contrast, writes from a sacramental imagination. Severian’s journey is not a straight allegory of justification but a pilgrimage of sanctification in time; Augustinian rather than Lutheran. His progress is mediated by relics, ritual, and memory; he acts within a cosmos thick with grace, not merely under judgment.

Where Bunyan’s pilgrim knows God through faith, Wolfe’s must become capable of bearing divine light. The difference is not between knowledge and ignorance, but between immediacy and participation. In the end, Severian does meet his Judge directly, Zadkiel, the angelic intelligence who tests his worth. The relics, the mercy, the remembered sins all converge into a redeemed act of will. If Bunyan’s City of Destruction is escaped by belief, Wolfe’s Urth is renewed through action. The one ascends by grace alone; the other redeems by grace embodied. Both envision the pilgrim’s path as moral theater, but Wolfe’s curtain falls not on arrival, but on restoration.