At 6 AM I was wakened by an intermittent pop-pop … pop. It wasn’t the dog. What was it? Sluggish and slow, I got out of bed to investigate. Not the cats nor the kids. Moving to the kitchen I saw the open window and realized it was the roofers starting early on my neighbor’s house to beat the forecast heat wave, nail gun used only sporadically in an effort to be polite. They didn’t start roofing in earnest until 8 AM when the rhythm increased to a machine gun pace.

Unfamiliar sounds wake us and alert us to potential danger. What is new in our environment may be a threat. It wasn’t just that the popping resembled a small caliber firearm, it was more that it was a novel sound, atypical for the neighborhood.

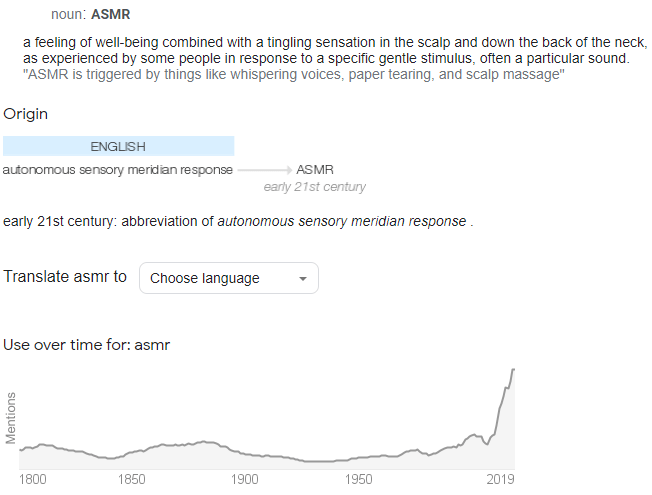

Sound is powerful and its importance is evident. Music is universal – it elevates, celebrates, and keeps time – binding us in a collective. And individually it can be purposeful: In a martial setting – kiai, in meditation – mantra, and YouTube has an abundance of videos with sounds to induce ASMR.[1]

Well done movie soundtracks create and augment the emotional tenor of any scene – the soundscapes of horror movies prove how effective they can be.

The popping that wakened me was not loud but my brain amplified it over the ambient fan noise. I do not sleep well, and I cannot sleep without white noise running constantly. I suspect that without the susurrating I would be too attentive to every random noise in the house and every intruding thought.

Current research demonstrates that what we hear can exacerbate (and induce?) health problems. Looking at the historical record, Alex Velez published a paper that suggests the soundscape of the Great Plains was a plausible cause of “prairie madness” (Velez, A.D. “The Wind Cries Mary”: The Effect of Soundscape on the Prairie-Madness Phenomenon. Hist Arch 56, 262–273 (2022).)

There is good evidence that there was a rise in cases of mental illness in the mid-1800’s to early 1900’s, including on the Great Plains.[2] The vast emptiness and distance between homesteads is isolation inducing and (as Covid lockdowns have show us contemporaries) isolation is terrible on mental health. Velez, who studies the evolution of human hearing, looked at possible causes beyond geography.

To study the soundscape Velez used recent recordings from the plains in Nebraska and Kansas, which captured noises like the wind and rain, and compared them against recordings from urban areas that contain both weather sounds as well as the din of traffic. He then analyzed the spectrum of frequencies in the recordings and compared the results to each other as well as against the frequencies that the humans can hear.

Velez found that the urban sounds spread across the range of human hearing and were diverse thereby forming something like white noise. But out on the prairie, the sounds coincided with a particularly sensitive part of the human hearing range the brain notices more readily. The abstract puts it academically:

Prairie madness is a documented phenomenon wherein immigrants who settled the Great Plains experienced episodes of depression and violence. The cause is commonly attributed to the isolation between the households and settlements. However, historical accounts from the late 19th and early 20th century also specify the sound of the winds on the plain as a catalyst. A number of conditions such as acute hyperacusis can cause increased sensitivity to environmental sounds. These conditions can result from high stress and have been known to cause behavior consistent with descriptions of prairie madness such as depression, insomnia, and violent behavior. Audiometric analysis of general human hearing patterns, combined with data on the effects of wind and open environments on hearing and communication, can be used to establish the effect of soundscapes on daily life. Thus, historic documentation and psychoacoustic analysis add to the understanding of life for settlers on the Great Plains.

Less academically, a newly arrived settler, used to the sounds of a more urban, small-town, or forested environment, might come to find every noise that breaks the silence to be as dreadfully distinct (and aggravating) as drumming fingers in a board meeting.[3]

______________________

[1] ASMR likely peaked in 2020

[2] Ailments as an historical artifact? I wonder if madness as an early 19th century phenomena is the equivalent of ADHD today… over-attention to behavioral symptomology leading to over-diagnosis? It merits a robust analysis.

[3] Jacob Friefeld, a research historian at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum, has written extensively on the Homestead Act. His research does not indicate widespread prairie madness and he has pointed out that modern recordings Velez used likely are missing some sounds early settlers would have heard, like the howl of wolves or the rumbling of herds of bison; and those settlers living in sod houses may have heard the sound of insects or other creatures living in the dirt walls. A Lovecraftian soundscape?