The Sisters of Mercy released Floodland in 1987, a record of industrial choirs and end-of-empire glamour. On Lucretia, My Reflection, Andrew Eldritch croons about dum-dum bullets and shoot to kill, not as moral protest but as soundtrack for dying empires. The reference wasn’t metaphorical. “Dum-Dum” was a real place: a British arsenal outside Calcutta where engineers, tired of the anemic stopping power of the .303 round, filed the tips off their bullets so they would flatten and expand on impact.

The British military manufactured these modified Mark II bullets at its Dum Dum Arsenal, situated on the outskirts of Calcutta (Kolkata), starting in 1895, … British soldiers shooting filed-down Mark II bullets … wreaked havoc … in expanding and fragmenting on impact, the modified Mark II served to kill.

It worked spectacularly. It also scandalized the European conscience.

By 1899, the major powers were embarrassed enough to make a rule. At The Hague they pledged, “to abstain from the use of bullets which expand or flatten easily in the human body” (Rule #77). Civilization congratulated itself for discovering that there were, apparently, polite ways to shoot people. The ban on “dum-dums” was less about mercy than optics, like all political decrees. It allowed Europe to keep its wars but launder its conscience, to substitute decorum for restraint.

The soldiers were unconvinced. Colonel C.E. Callwell, whose Small Wars: Their Principles and Practice (1896) was the Empire’s field manual on colonial conflict, had already written that “in savage warfare it is often essential that the enemy should be disabled at once … the ordinary bullet passes through his body and he continues to advance.” In other words, the so-called “civilized” bullet failed the one test soldiers cared about: stopping power. To the imperial mind, the quick-killing round was more merciful.

Rudyard Kipling caught the mood best in 1898:

And there was no sound of the strife,

Save the little burnt-silk whisper of the four-inch rifled shell;

But the dum-dum does the work of the Lord as well.

The men who fought wanted ammunition that was swift, decisive, and final. The men who legislated preferred a tidy conscience. The result was compromise disguised as civilization: a treaty that forbade brutality only in design while preserving it in effect. The Victorian instinct to civilize savagery remains an ironic and hypocritical perspective; violence is acceptable so long as it remained well-dressed.

After the Hague had tidied up the ethics of bullet design, the technology stood still for half a century. The “rounds of empire” (the British .303, the American .30-06, the German 7.92×57, and the Russian 7.62×54R) marched through two world wars largely unchanged. They were full-power cartridges built for bolt actions, marksmanship, and long-range killing. The Hague had forbidden expanding bullets, but not heavy ones.

Habit of doctrine must have created inertia. Each of these rounds is similar enough in performance, at 300 meters they remain supersonic and transfer similar energy. The effective range of the rounds far exceeded documented average engagement distance. The Boer War (watch Breaker Morant!) was perhaps one of the few wars where rifle engagements were frequently beyond 300 meters, yet from 1899 through Korea (1950-53) the issued ammo changed little. It took until 1952 to fully appreciate what multiple wars provided data for, that hits on target mattered far more than terminal energy.

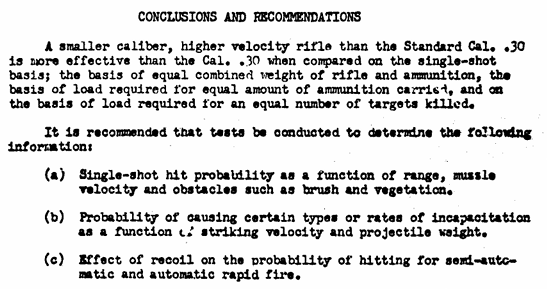

Aberdeen’s Ballistic Research Laboratory produced Donald L. Hall’s Ballistics Research Laboratory Memorandum No. 593 (1952) which reframed the problem in pragmatic terms. Hall modeled single-shot hit and kill probabilities across a family of rifles, explicitly holding total weight of rifle + ammunition as a constraint and asking which combination produced the greatest expected kills. Hall ran the weight math and produced the striking operational comparison. With the combined weight of gun and ammunition fixed at fifteen pounds, the expected number of kills for a cal. .21 rifle is approximately 2.5 times that of the standard cal. .30 rifle; and, with 96 rounds fixed, the cal. .21 system yields a 3.6-lb reduction in load (about 25% less) than the .30 system. Hall further calculated that to equal the expected number of kills produced by the 15-lb cal. .21 system, a soldier with a .30 M1 would have to carry an additional 10 lbs of ammunition (a total of ~25 lbs). Thus:

That calculus, reduce weight, improve flatness of trajectory, and thereby increase practical hits in the ranges that actually matter, is the analytic engine behind the doctrinal change to Small-Caliber, High-Velocity (SCHV) rounds. Hall did not mince words: the metric of interest was expected kills per unit weight and per man. Vietnam supplied the operational proving ground where those analytic claims could be tested in dense foliage and short-range contact.

The outcome is mildly perverse. The “high-powered” military rifle of 1914 is now a standard hunting caliber; civilians lug what soldiers once found too heavy, while soldiers fire what sportsmen call “varmint” rounds. The persistent myth that 5.56 was “designed to wound” originated as Soviet propaganda and stubborn rumor. The archive is clear enough: procurement documents emphasize hit probability, reduced recoil impulse, and increased ammunition carriage per soldier, not an intent to maim. If a SCHV FMJ fragments at high velocity and produces horrific wounds, that is a consequence of physics and impact dynamics, not a design mandate.

The irony deepens when you consider that police departments, operating under domestic law and insurance risk, use the very ammunition international law forbids the soldier. A standard defensive pistol round (Speer Gold Dot or Federal HST) is engineered to expand quickly in soft tissue so it stops the target and does not over-penetrate. A military FMJ, by contrast, is designed to punch through barriers, helmets, and thin steel. The difference is not moral but mission functional.

Thus, we live under two perfectly rational hypocrisies. In war, expansion is banned as barbaric; in policing, it is required as responsible. The treaties call one “unnecessary suffering” and the other “public safety.” Both are correct within their domains. Both achieve their practical aims. The difference in mission reveals an ironic contrast: the better trained and more technologically equipped a military becomes, the less efficient it looks on paper. Civilians and police resolve most armed encounters with a handful of rounds at conversational distance; soldiers expend thousands per enemy casualty. “Hit probability” in Hall’s lexicon was never synonymous with marksmanship. It was statistical effectiveness. By contrast, the civilian or the patrol officer acts at close range, the targets are visible, the consequences immediate, and the moral accounting direct.

In 2023 when Measure 114 was first contested, I was incensed at the finding that it fell within established (Heller and Bruen) interpretations of the State regulation of the 2nd Amendment. The courts, I contend, still employ perversely dangerous logic, but if one distills the part that could be made logical it would be to apply Hall’s 1952 memo that proved capacity confers probability.

It isn’t cited as precedent, but Measure 114 repurposes Hall’s arithmetic in reverse. The logic is perfectly symmetrical: fewer rounds = less potential lethality. Measure 114 was sold as public safety, but its logic comes from a faith that safety can be engineered by restriction. Yet that is impossible. One cannot legislate moral humans into existence.

As I write this, Federally deployed helicopters circle over Portland. From Quantico (September 30, 2025), Trump boasts, “We should use some of these dangerous cities as training grounds for our military… How about Portland?” Once a President imagines a domestic city as a proving ground, the Republic is in grave danger.[1] I hear the Anti-Federalists shouting from 1788: “The liberties of a people are in danger from a large standing army… the rulers may employ them for the purpose of enforcing their own ambitious views.” (Brutus No. 8)[2]

Portland is living that reality as helicopters beat above residential streets and we should remember when masked and unbadged federal agents “secured” intersections from unarmed protestors. A people disarmed of parity are not made safe; they are made compliant. The potential National Guard deployment over Portland is a reminder. The Second Amendment was not written for deer season. It was written for that helicopter.

_______________________

[1] I write with a wry smile about the Republic now being in grave danger since the first domestic use of federal military power came almost before signature ink on the Constitution dried. Just five years after its ratification, in 1794, President Washington personally led nearly 13,000 militiamen into western Pennsylvania to suppress the Whiskey Rebellion, an uprising against the new federal excise tax. The irony was biblical: the same general who had defied imperial taxation now marched under constitutional authority to enforce it. Washington justified his action under the Militia Act of 1792, which permitted federal use of state militias to “suppress insurrections and enforce the laws.” The episode established the founding paradox: liberty secured by force, consent guaranteed by compulsion.

From that moment forward, domestic deployments bifurcated into what most historians would label abuses (bad) or affirming (good). From today’s moral perspective, the abuses include, the Railroad Strike of 1877, Pullman Strike of 1894, and Bonus Army eviction of 1932; and affirming actions taken against states to enforce federal law (as in Little Rock, 1957 and Ole Miss, 1962).

Regardless of the legal excuse used (the Insurrection Act of 1807, the Posse Comitatus Act of 1878, or Cleveland’s clever assertion that the obstruction of the mail justified squashing the 1894 Pullman Strike) the fact remains that discretion rests with the President. If the President declares necessity, legality follows by proclamation. Which leads back to the concerns best voiced by Brutus:

[2] Brutus’s Eighth Essay (20 December 1787) warned that liberty could not survive a standing army commanded by the executive and financed by the legislature. His argument was not logistical but anthropological: once rulers command a professional soldiery, they no longer depend upon citizens for obedience, and once citizens grow accustomed to soldiers enforcing domestic order, they cease to imagine themselves free. “The liberties of a people are in danger from a large standing army,” he wrote, “not only because the rulers may employ them for the purpose of enforcing their own ambitious views, but [because] the people may, in the end, become indifferent to their use.” Indifference is what Brutus feared most.

Hamilton’s reply in Federalist No. 26 (22 December 1787) offered a mechanical faith in restraint. Yes, armies might be dangerous, he admitted, but Congress’s two-year funding limit and the people’s electoral vigilance would serve as “most effectual precautions.” Where Brutus demanded virtue, Hamilton substituted the accounting of the treasurer. (Hamilton always followed the money.) His reasoning was ambition would check ambition, fear would check fear, and liberty would emerge from the friction.

Madison refined the same idea in Federalist No. 51: “If men were angels, no government would be necessary.” He did not deny the darker nature of power but hoped to channel vice through competing institutions that would make tyranny inefficient. In Federalist No. 46, he extended this to the military sphere, arguing that the federal army could never endanger liberty because it would be “a small fraction of the militia,” and that the states and the people, “being armed,” would form a bulwark against centralized incursions.

Madison was a shrewd anthropologist and an honest historian. He later regretted his early support of the Hamiltonian vision, but he captured the enduring logic behind the Second Amendment: the parity of firepower between citizen and state as the last defense of a free people.