Business is war, and war is business.

— Sean Connery as Captain John Connor, Rising Sun (1993)

In the early 1990s, Rising Sun captured an America unsettled by Japan’s economic ascent. Beneath its murder mystery plot lay a parable about national confidence; the fear that Japan’s discipline and precision might eclipse Western improvisation and ingenuity. The film’s boardrooms and neon skylines served as metaphors for a civilization poised to out-compete the United States. [1]

Within a decade Japan’s vaunted miracle collapsed into the long deflation: asset bubbles burst, demographics turned, and credit ossified. [2]

Noah Smith’s “Can Anything Knock China Off Its Mountain?” (Oct 10 2025) title suggests we are watching a sequel. But it’s a title-bait inversion piece.

China occupies Japan’s former role in the Western imagination: the efficient rival and supposed successor, the civilization that “plays the long game” by centralizing power to direct its economy. Once again, declinists forecast an American eclipse. [3]

Beijing’s pretend-to-work offices illustrate an endemic weakness. What began as a satirical sketch about going through the motions has become a business model for the under-employed middle class. Anthropologist Xiang Biao of the Max Planck Institute captures the mood succinctly: “This is a collective pretense. People are unhappy with social norms yet feel there are no other opportunities.” Mid-career professionals, displaced from real-estate firms or tech conglomerates, now rent desks to perform productivity and stave off shame, much as Japan’s salarymen once rode the subway to nowhere after their bubble burst.

This culture of ritualized work exposes the hollowness beneath China’s growth narrative. Its productivity is performed, not earned; its currency strength not trusted. China is a “Potemkin-village economy,” output without profitability, employment without purpose. It demonstrates how an authoritarian system can imitate growth. China’s ghost cities and unoccupied towers (buoyed only through state sponsored subsidies) stand as the modern equivalent of the pharaohs’ pyramids: monumental expenditures of labor and capital devoted to the worship of power. They are tombs for productivity: impressive from a distance, but lifeless within. [4]

Similarly, treating China’s $3.3 trillion in reserves (of which roughly $760 billion are U.S. Treasuries) as a geopolitical weapon misread the balance of power. The recent Bloomberg article by Mihir Sharma that Smith cited suggests that China’s dollar reserves are a point of leverage, allows it to bully Washington in trade or use its reserves as diplomatic leverage (An odd contra-citation, given his own Bloomberg articles: World is Stuck with The Dollar as the Reserve Currency, and Relax. We’ll Survive China’s Sales of U.S. Debt). History offers no precedent for a creditor country successfully coercing its debtor when the debt is denominated in the debtor’s own currency. Beijing cannot compel the Federal Reserve to act. In any confrontation, the Fed can expand its balance sheet, and investors will absorb the excess. The liquidity hierarchy is asymmetric. The reserves China carries are the necessary stability buffer in a dollar dominated world, not a weapon against it. Those holdings secure liquidity for China’s import-dependent economy and insure the renminbi (RMB) stability at the cost of perpetuating dependence on the U.S. Treasury market. Every dollar China accumulates deepens its exposure to American fiscal and monetary policy. Until China produces a freely convertible safe asset and an open capital account, its financial reach remains contingent on U.S. monetary architecture rather than an alternative to it. [5]

However, if China wanted to liberalize its capital account and promote the RMB as a freely traded global currency, doing so would erode the very political control that defines Xi Jinping’s regime. Convertibility requires trust in markets, transparency in governance, and legal predictability: all antithetical to a one-party state’s logic of control.

The behavior of China’s wealthiest confirms the regime’s monetary fragility. Capital flees whenever channels open; into Hong Kong insurance products, Singapore family offices, Dubai property, and Canadian real estate. All fiat currencies rest on confidence and the RMB lacks both the convertibility and legal controls to provide confidence, even to its own citizens.

The story is not new. In the late 1980s, Japan also ran enormous trade surpluses, accumulated record reserves, and was predicted to eclipse the United States. It never did. The yen failed to displace the dollar because Japan’s financial system was structurally incapable of underwriting a global currency. And even now, the yen has far better global confidence than the RMB.

As I’ve written elsewhere in my review of Debt: The First 5,000 Years, Graeber mistook obligation for ontology. His anthropological moralism (an extended re-hash of Marcel Mauss) confuses the social genesis of debt with its modern metaphysical form. Graeber saw debt as a moral chain; central banks wield it as a policy instrument.

The distinction matters. Mauss described exchange as a moral totality—a web of reciprocity binding giver and receiver in mutual recognition. But modern finance operates through abstraction: debt no longer binds persons, it binds systems. It is a symbol recursively referencing itself.

Graeber never grasped this ontological shift because he treated money as the residue of human promise rather than as a reified medium of power, an institutionalized ontology that exists independently of individual intention. He saw people where the world now tracks capital flows.

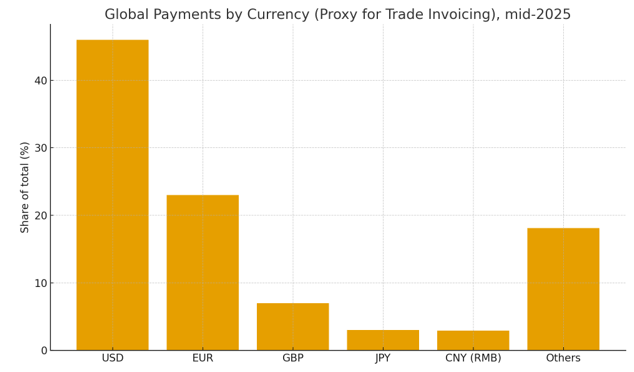

Modern debt has a reified status that is independent of human obligations even as its utility remains rooted in confidence. Debt now is morally empty at a global scale. It functions not as a social relation but as an engine of confidence, a self-perpetuating claim upon future productivity. True monetary sovereignty arises not from hoarding another’s currency but from persuading the world to hold yours. By that measure, the only one that counts, China still lags America by an order of magnitude. The IMF’s COFER database places the RMB at under 3 percent of global foreign-exchange reserves. SWIFT’s tracker puts its share of cross-border payments around 2.9 percent, compared to 46 percent for the dollar and 23 percent for the euro.

Why does any country hold dollars?

The foundations of dollar hegemony rest on institutional credibility and maritime dominance. The 1944 Bretton Woods agreements formalized a global credit order underwritten by U.S. naval supremacy. The dollar’s convertibility into gold until 1971 provided currency legitimacy, but what preserved its primacy after the Nixon reforms was the ability of the United States to guarantee the flow of trade and energy. Every container ship, every tanker, and every shipped transaction was ultimately insured under an American security umbrella, allowing Lloyd’s to price global risk against the stability of U.S. power (and, crucially, excluding or constraining vessels tied to sanctioned states; notably, Russian-flagged and many China-affiliated “dark fleet” ships operate outside Lloyd’s and International Group P&I cover, relying instead on under-capitalized domestic or shadow insurers, a structural vulnerability that underscores the link between maritime insurability and the credibility of Western order).

China’s dilemma is precisely this: it can build ships but cannot guarantee any shipping lane. Furthermore, China cannot offer a credible promise that trade conducted in RMB will be protected and liquid in crisis. Until China can convince the world that it, not America, secures the freedom of exchange, its currency will remain provincial.

Currency strength and military reach are co-dependent. The People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) now fields the world’s largest fleet by hull count, but this metric is deceptive. Most of its ships are coastal combatants and diesel-powered auxiliaries, not the deep-water, nuclear-propelled carriers, cruisers, or submarines that define sustained expeditionary capability. By tonnage, the PLAN’s total displacement remains less than half that of the U.S. Navy, whose nuclear carriers and submarines give it unmatched global endurance. [6]

China’s maritime capabilities remain defensive and regional. It relies on imported hydrocarbons for more than 70 percent of its oil and nearly all of its fertilizer inputs: strategic dependencies that recall Japan’s vulnerabilities of WW2. The chokepoints of the Strait of Malacca, Hormuz, and the South China Sea remain under coalition observation and, if necessary, interdiction. The “String of Pearls” ports and Belt-and-Road logistics hubs are defensive compensations to limit exposure.

China’s state-directed innovation machine excels at scaling and incremental improvement but struggles with frontier discovery. Private-sector dynamism has been blunted by Xi Jinping’s centralization; anti-tech crackdowns since 2020 have chilled risk-taking. Patents and AI models multiply, but Western institutions still tend to lead in scientific influence, citation impact, and foundational software/platform innovation. Chinese volume is impressive, but U.S. and European researchers continue to dominate in terms of per-paper impact and cross-border leadership (e.g., China’s share of top-5% AI publications reached parity in 2019, yet U.S. works still draw more international citations). China’s STEM output gives it immense intellectual potential, but, I contend, it is not supported by open feedback loops and capital mobility. Those key requirements remain under Party control. [7]

Nevertheless, I do see the “China threat” narrative as necessary to re-energize Western competitiveness.

Trump’s approach to foreign policy is bombastic and crude but not strategically fatal. Unilateralism and tariffs have alienated allies, but they have also jolted Europe and Asia into recognizing the need for greater military independence and resiliency. Inadvertently (Niall Ferguson may claim intentionally), this has catalyzed NATO re-armament and European defense integration; outcomes that strengthen, rather than weaken, the Western position relative to China.

Niall Ferguson’s Chimerica captures the paradox of mutual dependency: China’s surpluses fund U.S. deficits, tying both economies together. He argues that the second Cold War is asymmetrical: China depends on Western markets and technology far more than the reverse. Ferguson’s likely assessment would read: ‘China is formidable but brittle; the United States is erratic but regenerative.’ Smith is right that America’s self-inflicted errors (tariffs, alliance strain, political dysfunction) have made it easier for China to expand regional influence. But the claim that this translates into financial hegemony confuses balance-sheet mass with monetary sovereignty. (Just consider the recent investment strategy release by J.P. Morgan, bank deregulation in America is predicted to unlock another $2.6T in financial capacity, something China could never dream of doing.)

China’s apparent dominance is an artifact of scale. Its reserves signal exposure, not strength; its fleet cannot protect its trade lanes; its factories rely on imported fuel; its agriculture upon imported fertilizer; and its innovation engine runs on imitation, not originality. Trump’s diplomacy may be crude, but it has reawakened the West.

America can survive Trump. I am not sure China survives Xi.

_____________________________

[1] See also my use of Rising Sun in Tik Tok.

[2] Since the Bretton Woods system, central banks have been perceived as the single most important determinant of national economic performance. Yet the European Central Bank Working Paper No. 3124 (Stracca, 2025) demonstrates where this conventional wisdom fails, especially in the Chinese context. Stracca’s cross-sectional analysis of 63 economies from 1980–2023 identifies institutional quality, proxied by the World Governance Indicators (Rule of Law), as the dominant determinant of macroeconomic stability. Once institutional variables are included, traditional monetary indicators, central-bank independence, exchange-rate regime, and inflation-targeting frameworks, lose statistical significance.

The finding is conceptually elegant and empirically disruptive: centralization, even when transparent and rules-based, is less determinative of stability than distributed cultural adherence to the rule of law. Institutional strength accounts for roughly 30 percent of cross-country variance in inflation volatility, a stronger correlation than any nominal or policy variable.

Nations with transparent legal systems, predictable contract enforcement, and credible governance display lower inflation variability across all monetary regimes. The implication is profound: macroeconomic moderation is an emergent property of lawful societies, not a direct artifact of monetary policy. China’s model (dependent on central planning, administrative fiat, and data opacity) lacks the feedback mechanisms that generate durable equilibrium in the West. Stracca’s findings suggest the U.S. model exhibits antifragility: resilience to exogenous shocks (pandemics, energy crises) due to transparent market discipline. By contrast, China’s system exhibits rigidity and latent volatility, amplified by political concentration.

[3] “In its brief 232 years of existence … never bet against America.”

— Berkshire Hathaway Shareholder Letter, 2020

As Warren Buffett likes to remind his shareholders, “never bet against America.” Milton Friedman made the same point in sterner terms: that only free institutions possess the capacity for self-correction. Together they distill the argument better than any macroeconomic model: power and prosperity endure not through perfection, but through feedback, failure, and reform. China’s command model suppresses these, and so its apparent stability conceals fragility.

[4] Ghost Cities reflect a spatial constraint identified by Desmet, Nagy, and Rossi-Hansberg’s 2024 NBER paper, Human Capital Accumulation Across Space, provides the formal economic proof. Their model shows that regional development depends less on capital injections than on the local cost and density of human capital formation. Growth, once concentrated, tends to persist and efforts to equalize opportunity across space often reduce global efficiency. In other words, pouring money into empty hinterlands doesn’t create new centers of productivity; it redistributes population away from where human capital naturally clusters.

This is precisely the pathology of China’s state-directed urbanization. The relocation of millions to newly built inland cities was meant to “balance development,” but it has largely transferred fiscal strain rather than created self-sustaining economies. The spatial model predicts this failure: when you relocate people without simultaneously relocating dense skill networks, innovation externalities vanish. What remains are concrete shells financed by moral hazard.

In the Chinese context, ghost cities are not just real-estate oversupply; they are physical expressions of mispriced human capital, the illusion that capital expenditure can substitute for organic knowledge accumulation. No number of high-speed rail lines can accelerate diffusion if the human capital gradient itself is steep.

Thus, even in the most authoritarian form of state capitalism, geography remains the ultimate constraint. You can move bodies; you can’t move ideas.

[5] The People’s Bank of China (PBoC) operates as an administrative extension of the Chinese Communist Party rather than an independent monetary authority. Its governor is appointed by and accountable to the State Council and the Central Committee, without statutory independence (something Trump appears to hope to achieve).

In contrast, the Federal Reserve, European Central Bank, and Bank of England possess explicit legal mandates and procedural transparency. They use open market operations and public guidance, while the PBoC relies on administrative directives to state banks.

China’s economy faces persistent deflationary pressure driven by structural factors: overcapacity, aging demographics, weak household consumption, and excessive debt. The PBoC’s response (targeted liquidity, reserve ratio cuts, and moral suasion) reflects a fear of capital flight rather than confidence in demand stimulus. And the fear is justified; Chinese citizens continue to export (if only to Hong Kong) capital abroad whenever possible (spurring, along with Russians, a boom-bust in Dubai).

Capital controls isolate China from global financial discipline. Foreign investors cannot freely move capital, and domestic investors face severe restrictions on foreign holdings. Consequently, the RMB lacks the price-discovery mechanisms (sovereign yields, credit spreads, currency swaps) that define confidence in other fiat systems.

The result is a kind of financial mutually assured dependence: the United States owes the debt, but China depends on its safety. Russia, I argued at the start of the Ukraine war, was much better insulated from the Western banks than China is today. The very success of China’s export model deepens its entanglement with the dollar. The more dollars it earns, the more it must recycle into U.S. assets to prevent its own currency from appreciating.

As a tangent, the recent upsurge in the price of gold, is in part explained by the work of Chinn and Frankel – NBER Working Paper Series, August 2025, “Reserves, Sanctions and Tariff in a Time of Uncertainty: “We extend those results by showing that financial sanctions imposed by the United States also induces increases in holdings of other reserve currencies, and gold. These effects are sizable, even in the short run, on the order 6 percentage points of foreign exchange reserves.”

[6] The impact of drones and hypersonic missiles in a China vs U.S. conflict is a false analogy when drawn from the Ukraine vs Russia war. The United States has neither the intent nor the strategic need to invade China. Should Washington ever seek to dismantle China’s economy or compel confrontation, it would rely on maritime and financial warfare, not invasion. The template comes from the Russia sanctions. Applied to China, a similar strategic implementation (targeting maritime access, dollar clearing, and global energy logistics) could cripple its trade-dependent economy without crossing its borders. The effect would be devastating for China and merely inconvenient for American consumers, reflecting the asymmetry of dependence: China’s survival hinges on open sea lanes, while the United States’ power projection is the very mechanism that guarantees them (RAND Corporation, The Effectiveness of U.S. Economic Policies Regarding China Pursued from 2017 to 2024, 2024; RAND Corporation, Understanding and Countering China’s Maritime Gray Zone Operations, 2024).

[7] The Center for Strategic and International Studies (Sept 2025), provides a policy recommendation to mitigate “Competing with China’s Public R&D Model: Lessons and Risks for U.S. Innovation Strategy” : “Importantly, providing multiyear federal research grants would stabilize long-term research planning for firms and universities alike. Equally critical are steps to revitalize the talent base through expanded domestic STEM fellowships, skills-based reforms to visa policies, and active retention of U.S.-educated international talent. These steps are essential to offset China’s numerical demographic advantage and rapidly rising domestic researcher pool. While China benefits from sheer scale in annual STEM degree production, its broader demographic outlook is far less favorable than that of the United States, which has a younger population profile and, until recently, sustained immigration flows. The challenge for the United States is therefore not absolute numbers but ensuring that its institutional and talent advantages are funded at levels that will enable the United States to successfully compete for global innovation leadership. Drifting away from the United States’ long-term commitment to leadership in science and innovation will compromise not only technological competency but also the foundations of U.S. national security.” Important considerations in a post-Trump return to policy normalcy.

_____________________

Coda: Why High-Speed Rail (HSR) Don’t Mean Shite

For some, high-speed rail is a proxy for technological progress. But the assumption that the same infrastructure signals the same virtue everywhere is a geographic and economic fallacy: engineering prowess is not the same as economic purpose.

The argument that America needs high-speed rail rests on a category error. After World War II, Americans built suburbs, seeking space for growing families, at a time when high-speed rail was neither technically nor economically viable. Retrofitting HSR into that historical topology is the inverse of how Europe and Japan urbanized, where wartime destruction created a tabula rasa for density-first design. It mistakes what works in compact, continuous nations for what works on a continent. The United States is not Japan, nor Germany, nor even coastal China. It is a polycentric federation of cities separated by thousands of miles of low-density space.

High-speed rail only becomes efficient when three conditions align: (1) short intercity distances (100–600 miles), (2) high linear population density (10–15 million residents along a corridor), and (3) consistently high seat occupancy (above 70%). The United States satisfies few of these conditions. A hard test is revealed preference: after half a century of studies, only two U.S. corridors (Boston -> DC and LA -> SF) demonstrate value-of-time arguments than might pencil. (If we ever price aviation/highway externalities at full social cost, a few corridors may flip. But that would require a global pricing of externalities – good luck!)

The World Bank 2019 report on China’s HSR expansion notes that only a handful of its busiest lines (Beijing–Shanghai and Guangzhou–Shenzhen) come close to operating profitability, while “most routes operate at persistent losses offset by fiscal transfers.” These are nations with urban densities America cannot and should not replicate. The California High-Speed Rail Authority’s 2023 Business Plan projects a capital cost exceeding $128 billion, translating to well over $100 million per kilometer, roughly five times China’s median construction cost. (Wonder about permit and compliance friction….?)

China’s lower HSR cost per kilometer is enabled not by engineering excellence alone, but by structural advantages: lower labor, cheaper/resettled land, cookie-cutter standards, equipment amortized across hundreds of lines; financing centralized via China Rail Investment Corporation; deficits socialized.

The OECD International Transport Forum analyses find HSR viability declines rapidly beyond 800 km and hinges on exceptionally dense, high-frequency urban demand.

Decry all one wants, but the U.S. transportation grid built for automotive and aerial freedom. Its major cities are nodes, discontinuous urban clusters, where distance and low density erode rail economics. American metro cores are often spaced on the order of 1,000–1,500 km apart, while similarly sized European corridors tend to fall in the 400–600 km range, and Chinese coastal city clusters cluster within 200–400 km of each other.

HSR’s defenders can point to energy efficiency, and they are not wrong in principle. At full capacity, electric trains consume less energy per passenger-mile than planes or cars.

But that’s a big if.

Low utilization rates erase the advantage; empty seats consume as much energy as full ones. And because U.S. corridors cannot sustain Tokyo-level ridership, the energy calculus collapses.

But the critical measurement is not how fast people travel but how efficiently goods move. Here the United States excels. The real metric is ton-miles, not train-miles.

Free markets solve for equilibrium. The United States, by combining modes, maintains one of the world’s most efficient freight ecosystems: oceans, rivers, interstates, and pipelines integrated with rail into a friction-minimized network that arguably moves more economic value per energy unit than most large economies. (Yes, all modes are subsidized; the salient point is marginal net benefit: U.S. aviation/highways deliver higher passenger-mile throughput per budget dollar than HSR.)

HSR’s promise of efficiency vanishes when mapped against actual logistics performance: the World Bank Logistics Performance Index (2023) places the United States slightly ahead of China (3.8 vs 3.7) on infrastructure, competence, and timeliness. Agreed; it’s a tie on paper. The point is HSR’s scale hasn’t moved China decisively ahead on the very metrics it was meant to transform. Thomas Sowell would be quick to point out every dollar into HSR is a dollar not into ports, roads, or interstate bridges; projects with clearer cost-benefit and fewer speculative assumptions.

In the United States, freight moves on a multimodal lattice: trucks (~44 % of ton-miles), rail (~19 %), with barges and pipelines carrying most of the rest. Long-haul rail in America remains among the world’s lowest-cost land transport per ton-mile; corridor studies show multiple-fold fuel advantage over trucking, with external costs often one-sixth or lower than for trucking.

In China, by contrast, trucks handle roughly three-quarters of total freight by volume but account for only about one-third of ton-miles. Rail hauls the heavy industrial cargo; high-speed rail carries alomst none. China’s network moves more total mass but at higher energy and capital cost: shorter average hauls, less efficient engines, and weaker integration. Measured by ton-miles per unit of energy or GDP, the United States still moves more economic value per unit of freight energy than any large economy.

Hence, high-speed rail is not an economic necessity. It is a middle-class amenity with political cachet. What HSR offers, then, is not efficiency but symbolism: a visible monument to national competence. The reason HSR hasn’t been imposed on the American landscape is simple: it’s a categorical mistake the private sector intuits. You don’t build a network for density where what exists is distance.

Postscript

Or simply watch this interview with Frank Dikötter: