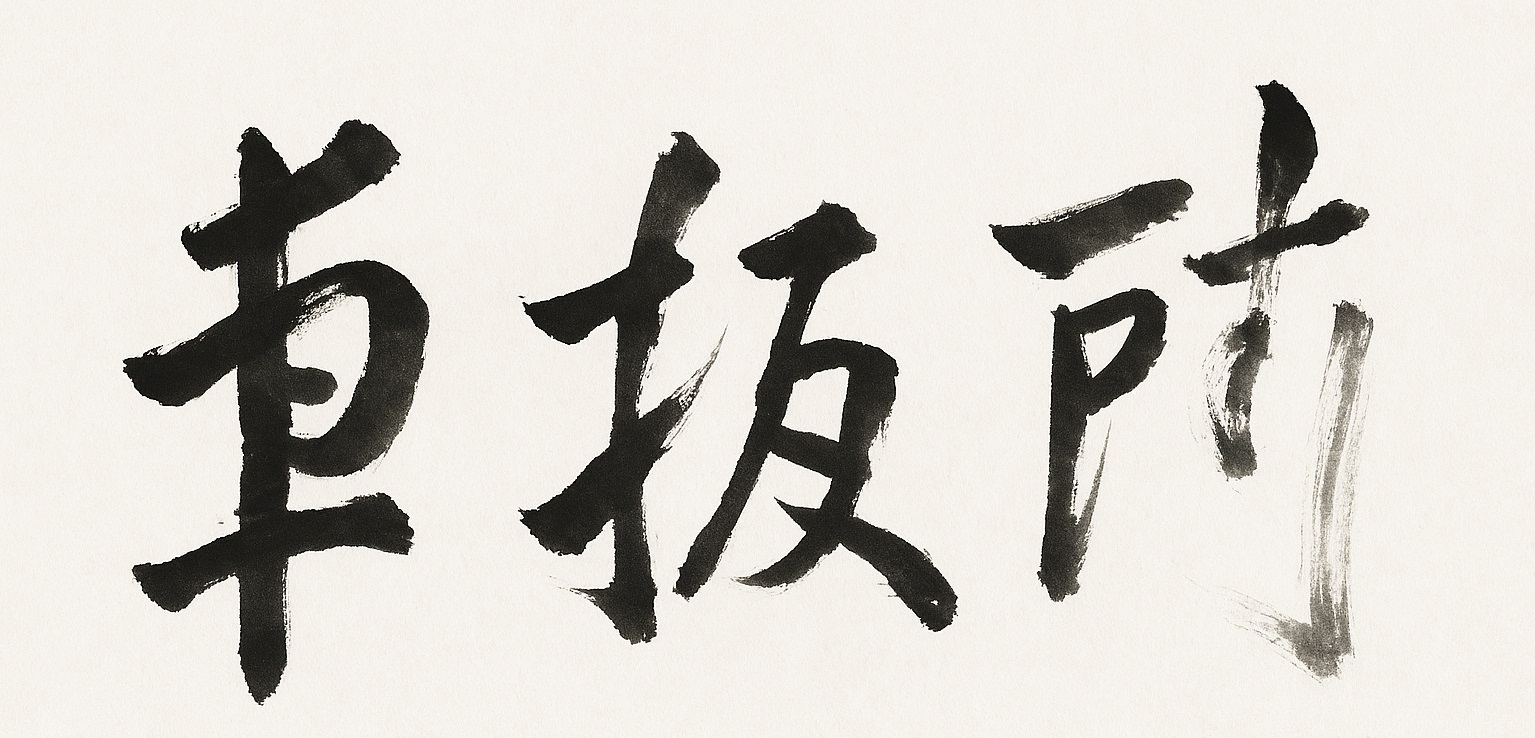

The Japanese formula shu ha ri comes from classical Japanese arts where preservation, rupture, and departure were recognized as essential phases of learning. Shu means to protect or obey. It carries the sense of guarding something fragile and important, like tending a fire that someone else lit. Ha means to break or detach. The character suggests a splitting open, a deliberate shattering of boundaries so that what was learned can be tested against reality. Ri means to leave or separate. The word points toward an unforced freedom, the moment when form dissolves and only the animating principle remains. In traditional Noh, tea ceremony, and swordsmanship, this cycle was never decorative. It marked the internal maturation of the practitioner as they moved from imitation to integration to innovation. Etymologically, the three characters reflect the pedagogical logic embedded across Japanese classical arts, where the student is expected to move from preservation to structural testing to natural expression.

There is an implied developmental progression in shu ha ri, but its origins are less linear. Shu was not simply obedience. It was custodianship. In Japanese craft culture, a student was expected to protect the lineage until they had enough depth to challenge it without collapsing it. Ha was not rebellion for its own sake. It was the honest collision between form and pressure. Ri was not improvisation for style. It was the return to simplicity after the weight and fracture of the first two stages had done their work. Understanding this etymological background matters because it reveals that the sequence is grounded in cultural assumptions about responsibility, tension, and creative adulthood. These assumptions match almost perfectly with the developmental arcs found in Nietzsche’s camel, lion, and child (Nietzsche, Zarathustra) and in the guild progression of apprentice, journeyman, and master. Nietzsche’s sequence is explicitly psychological rather than technical: the camel bears imposed values, the lion destroys inherited commandments, and the child generates new values through spontaneous affirmation. Even though Nietzsche was not writing for martial artists, the structural resonance remains striking.

Every tradition that takes itself seriously eventually discovers the same three step rhythm. First you submit. Then you break. Then you create. This sequence appears not because cultures borrowed from one another but because the nervous system learns in only a few durable ways. Shu ha ri gives the clearest vocabulary for it, and when it is understood in its original sense it clarifies the deeper logic of martial development. The pattern also aligns with Joseph Campbell’s departure–initiation–return cycle in the monomyth (Campbell, Hero, 1949), which describes the psychological transformation required of any figure attempting genuine self-overcoming.

Shu begins with obedience. You protect the form as if the form is the only thing you have. This is the stage where the Keys first appear, though at this point they remain only lines on a map. You can train quadrant play, universal attacks, line familiarity, geometry, and the permutations of progression thinking, but during shu these remain shapes without weight. They are treated as secrets rather than structures. The student obeys them without understanding them, like learning the grammar of a language without yet knowing how to speak.

Over time the student begins to feel the friction between what was taught and what the body senses under pressure. The standard footwork is too slow for the angle being created. The prescribed parry does not match the opponent’s intent. The kata fails to explain the shifting of weight in a contested draw. This is the break of ha. Here the Keys begin to spark. Quadrant play becomes tactile instead of theoretical. The law of opposites becomes a way of anticipating intent rather than a symbol of yin and yang. Universal attacks stop being categories and become real predictors that show the next line before it arrives. Geometry reveals itself as the skeletal structure beneath all viable movement. The student discovers that technique often blinds them to the line that truly matters. Ha is not rebellion. It is the recognition that tradition must collide with experience before it becomes knowledge. This rupture echoes Nietzsche’s lion, which must confront and negate the “Thou Shalt” before any creative act becomes possible.

This is the point where conceptual thinking becomes necessary. Without it, the student repeats forms with increasing complexity but no increase in competence. With it, the student notices that every art shares a handful of universal mechanics. A single insight reveals ten more, and the world of technique collapses into a few recurring shapes. The secrets lose their mystical veneer. What remains is pressure, angle, timing, structural integrity, and intent. These are the foundations that let the Keys operate. Here the student begins to understand the Keys not as esoteric knowledge but as universal grammars, analogous to the “deep structure” that linguists like Chomsky use to explain why different languages share similar underlying patterns.

When the break has done its work, the student enters ri. Here the Keys run on their own. Quadrant play becomes instinctive. The line is felt before it is seen. Universal attacks emerge unconsciously in response to pressure. Geometry traces itself underfoot without calculation. The law of opposites becomes a subtle sense of timing. The practitioner has returned to simplicity, but this simplicity is earned. It is Nietzsche’s child and the guild master in the same breath. It is Bruce Lee’s observation that after understanding a punch, it becomes a punch again. In Campbell’s terms, this is the “return,” where the hero comes back bearing a hard-won simplicity that others mistake for natural talent.

The cycle of shu ha ri is not philosophical. It is the very mechanism that turns technique into understanding. A student who refuses the burden of shu cannot internalize the Keys. A student who refuses the fracture of ha never sees why the Keys matter. A student who refuses the release of ri is trapped in ornamental complexity. Mastery requires all three because the human nervous system moves through all three whether we like it or not. These stages are a metabolic process: form, stress, and adaptation. (Pain as a Teacher.)

One of the persistent traps of training is the allure of secrets. People love the idea that a hidden piece of knowledge will transform their art. But every Key becomes visible only after the weight of repetition and the break of disillusionment. Once the magic trick is revealed as structure, most students feel cheated. They wanted the transcendent and instead find geometry. They wanted esoteric insight and instead find pressure. They wanted mystery and instead find line. Yet this is the real work. Nothing was ever hidden except the ability to perceive what was always in front of them. The magician’s trick is not that the technique is complex, but that it is so simple we look past it.

This disappearance of mystique is part of the break. It is the moment a student stops searching for shortcuts and starts studying structure. The Keys become clear only when the student has the honesty to confront what the art requires, which is not ornamentation but attention. Once the universal patterns are visible, technique dissolves into function. This is where aikido begins to resemble the older jujutsu schools: stripped to timing, leverage, angle, and the contested line of intent.

This connects directly to Campbell’s hero cycle. The departure demands obedience. The initiation demands rupture. The return demands recovered simplicity. A punch becomes a punch again not because the student has regressed but because they have carried the burden, endured the break, and let it resolve into clarity. That is why ikkyo and nikkyo only reveal themselves fully when understood as contested control in a weapon environment. In shu the student copies the shape. In ha they feel why the shape matters when the line is contested. In ri they simply take the line the opponent’s pressure offers.

There is no mastery without this sequence. The burden, the break, and the creation are the architecture of transformation. The Keys supply the universal grammar. Shu ha ri supplies the developmental path. Together they turn technique into insight and insight into expression. The purpose is not aesthetic. It is the capacity to move in a way that is both honest and structurally inevitable. This is the heart of the protective arts and the only way the art carries forward with integrity.