In Calydon, Oeneus made his offerings to the gods, and in the counting of names he forgot Artemis (Ov. Met. 8).

The first fruits rise in smoke to Zeus, Hera, the household powers, the immortals who tolerate men so long as men remember them. It is the old economy of reciprocity, the one James Frazer would later detail: the king as ritual hinge, the harvest as contract, the sacred as maintenance rather than belief. And Oeneus, for reasons no one remembers, left out Artemis.

It is not sacrilege. It is worse: it is carelessness. A god does not forgive being treated as an afterthought.

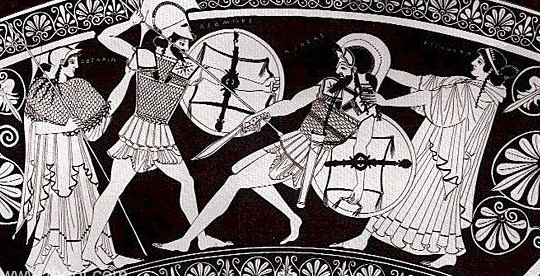

So Artemis sent a boar. Monstrously large, with a bristling ridge along its back like spears lifted for battle; its shoulders heaved, its jaws frothed, and it came ravaging Calydon.

The boar is divine judgment. It tramples vines and uproots young trees as if it resents the very idea of human order. Men go out with spears and come back in pieces. Dogs break their teeth on its hide. The thing is impenetrable, as Artemis herself is impenetrable: not merely untouched, but unclaimable: a parthenos (παρθένος), belonging to no hearth, no husband, no bargain. Untouchable. Unbending. And when she is slighted, she becomes purity sharpened into punishment.

Oeneus does what kings always do when their power fails: he calls for help and offers glory as payment. Calydon’s salvation becomes a competition. The best men of Greece arrive as if they can fix a divine insult with excellent posture and sharp bronze.

The heroes come: Theseus, Castor and Pollux, Peleus, and Meleager among them, depending on the teller’s roll call. And among them comes Atalanta, the sole female, fast, clean-eyed, a woman whose competence unsettles the men who thought excellence was their inheritance.

Some bristle at her presence; others stare too long. Meleager sees her and the myth shifts. His attention is immediate and fatal, the way desire is in old stories. He wants her admired. He wants her honored.

Atalanta’s arrow strikes first. It is a small wound, but it lands like a prophecy. The men see it and feel their pride slip on the wet stone of reality: the hunt is no longer theirs alone. The beast bleeds at a woman’s hand. The world has failed to respect the boundaries men drew on it. Artemis smiles.

Meleager is exhilarated. Others are offended. And the offended men begin, quietly, to prepare the argument that will follow victory: even if she helped, she must not be rewarded. They are not thinking about justice. They are thinking about precedent.

Meleager kills the boar, the myth grants him the climax. The monstrous body collapses into the earth, returning to the god who sent it. Calydon is saved.

And then Meleager does the thing that makes the story irreversible: he awards the spoils to Atalanta. The hide, the tusks, the trophy of salvation, he offers them to her as public fact: she mattered. In that moment, he tries to rewrite the law of the heroic world. He tries to make honor obey merit rather than gender, bloodline, or resentment.

Atalanta’s later “taming” belongs to a different story-cycle, but it throws a shadow backward: the fastest woman alive will one day be defeated not by speed, but by distraction, three golden apples (Ov. Met. 10). Conquered by luxury. That future does not explain Calydon, but it deepens it: excellence may win the hunt, yet still lose to the older machinery of desire, status, and social capture.

Meleager’s is a noble gesture. It is also suicide. Men will forgive a boar for being monstrous. They will not forgive a hero for changing the rules.

Meleager’s own family, his mother’s brothers, protest believing the prize belongs to them by right of male entitlement and clan dignity. The argument is not really about hide and tusks. It is about who gets to define reality. Anthropologically, the protest has the shape of a matrilineal tension: the maternal uncles act as if they are the rightful arbiters of prestige, as if the mother’s line retains authority over the male heir and the distribution of honor.

Meleager, hot with youth and certainty, answers insult the only way a Greek hero knows how: with killing. His uncles fall. The hunt’s victory is now stained with family blood.

And somewhere, offstage, Artemis watches with the serene patience of a god who understands that men will finish the curse themselves.

Althaea, Meleager’s mother, receives the news. The story tightens. In Greece, motherhood is not a soft role, it is a sacred jurisdiction. She is mother to her son, yes, but she is also sister to the men he has killed. Both relationships claim her. Both demand a verdict.

Here the myth reveals its cruel genius: Meleager’s life has been bound since birth to a firebrand, a piece of wood that will determine the length of his breath. Althaea holds the brand. She hesitates. She trembles between love and vengeance, and the trembling itself becomes a kind of prayer. Then she commits. She burns it. And Meleager dies not in battle, not in heroic spectacle, but because the household could not survive its own moral arithmetic.

This is the first true lesson in Diomedes’ lineage: the house does not collapse because enemies attack. It collapses because it turns upon itself.

Oeneus survives. That is not mercy. It is continuity. Old kings often live long enough to watch their mistakes become institutions. Calydon continues, but it does not heal. In later telling, Oeneus is displaced by kin, usurped, pushed aside, turned into a living relic of a reign that began with a forgotten goddess and ended with a dead son (Paus. Descr. 2).

He becomes what Greek myth loves most: the fallen patriarch. And he will, in some versions, find refuge not in Calydon but with Diomedes who will later suffer the same disease of homecoming.

Tydeus comes from the house of Oeneus, an Etolian prince of Calydon’s bloodline, whether son or later branch, carrying forward the same inherited violence. His inheritance is not merely royal blood; it is the family’s habit of solving moral problems with violence (Apollod. Bibl.). He grows into a man built like a spear point: sharp, narrow, and meant to enter things.

And like so many men in Greek story, he is exiled. The reasons vary, kin-slaying, quarrels, violated guest-right, but the essence is the same: Tydeus cannot be contained by his own city. He is too dangerous to keep, too valuable to kill. So he becomes a wandering asset.

He arrives in Argos and is taken in by Adrastus, king of political instincts. Adrastus sees what every ruler sees in such men: the state can use them. It can point the spear.

This is the second lesson in Diomedes’ line: cities adopt violent men when they need them, then pretend they were always civilized.

Adrastus binds Tydeus into the Argive order through marriage. And soon enough the marriage alliances embroil Thebes, because the Greek imagination cannot leave Thebes alone. Thebes is where family curses are not private tragedies but public infrastructure. Thebes is the city where your genealogy can kill you (Aesch. Sept.).

Tydeus becomes one of the Seven who march against it. They march because honor has hardened into law, and the law no longer has a human face.

Tydeus fights like the man he is: ferocious, competent, impossible to negotiate with. In later tradition, after he is mortally wounded, Athena comes to grant him immortality, an astonishing offer for a man so stained with violence (schol. Il.; later mythographic tradition). But Tydeus, still hungry, still enslaved to the old law of savagery, commits an act that disqualifies him: he tears into the skull of his enemy and eats the brains (schol. Il.).

It is not merely gore. It is the collapse of the boundary between hero and beast. Athena recoils. Immortality is withdrawn. She can tolerate violence. She does not tolerate the celebration of it.

This is the third lesson: the gods have standards for what kind of monster gets eternity.

Diomedes is Tydeus’ son, but he is not Tydeus repeated. He is the improved model: same steel, better tempering. Where Tydeus is rage, Diomedes is will. Where Tydeus is excess, Diomedes is discipline (Hom. Il. 5).

In Troy, he becomes the perfect Greek instrument. Athena favors him, not with love like she gives Odysseus, but with tactical sponsorship. She lends him vision, clarity, permission. In Book 5 of the Iliad, he rises into that rare state where a mortal seems briefly to outrank mortality.

He meets Aeneas on the field. Aeneas is brave, competent, and in Homer’s world he is still killable. Diomedes crushes him with a stone. Aeneas falls. The end is imminent. But the gods intervene.

Aphrodite herself descends to lift her son away, and Diomedes wounds her. The goddess bleeds. The boundary between human and divine is violated. A mortal hand draws blood from Love. It is the greatest mortal overreach in Homer and it is also the seed of later ruin. No one wounds Aphrodite for free.

Diomedes survives Troy. He returns. And here the story performs its oldest trick: the battlefield does not kill him; the household does. He wins the war but not the peace.

In later tradition his wife Aegialeia turns against him, through infidelity, conspiracy, hostility, rumor (Apollod. Bibl.). Sometimes the cause is framed as Aphrodite’s revenge; other versions make it more human and therefore more frightening: Diomedes is undone by politics, resentment, and the way a city forgets what it owes its protectors.

Either way, the result is exile. The hero who stood against gods cannot hold his own hearth. He leaves Argos, the way his father left Calydon. The pattern repeats.

Diomedes goes west. The story becomes colonial and local, as myths do when they settle into landscapes. He founds places, or is credited with founding them. The man becomes a landmark (Strab. Geog.; Plin. Nat. Hist.).

This is how Greek myth handles displaced greatness: it preserves it by scattering it. He is no longer a king. He is a legend with a coastline.

And now, at last, the Roman turn.

Aeneas survives Troy, bearing the gods and the household fire, carrying his people like a burden that cannot be put down (Verg. Aen. 2; 3). He comes to Italy not as a conqueror but as a destiny looking for ground (Verg. Aen. 7).

The Italians, threatened by this newcomer, look for old weapons. They remember Diomedes. They send to him: you fought Trojans; you almost killed their prince; come do it again. And Diomedes refuses (Verg. Aen. 11).

This refusal is the final refinement of the arc. It is the moment when the Homeric hero, who once wounded gods, becomes a man who will not fight the future. He has learned what war actually purchases. He has learned that even victory can be a curse. He has learned, perhaps, that some lines are protected not by skill but by narrative inevitability.

And Virgil, smiling like a priest of history, lets the old Greek hero step aside so that Rome can be born.

2 thoughts on “Diomedes and Aeneas”