Book Five of the Iliad contains some of the most outrageous acts of combat in all of Greek myth: a mortal wounds a god.

Homer opens the Iliad with the anger of Achilles and his retreat from the field of battle. His mother, Thetis, bargains with Zeus, and the war is no longer a simple contest of men but a stage of resentments managed by the gods. Book 3 tries to impose a political solution through a duel between the aggrieved parties, Menelaus and Paris, but Paris is spared death by Aphrodite. Book 4 shows that oaths, sacrifices, and truces are temporary at best. The gods hold counsel, and Athena persuades Pandarus to shoot Menelaus, breaking the truce. The ensuing battle of Book 4 is of equal measure: “For on that day many men of the Achaians and Trojans lay sprawled in the dust face downward beside one another.”

Into this deadlock Homer introduces Diomedes, son of Tydeus. “There to Tydeus’ son Diomedes Pallas Athene granted strength and daring, that he be conspicuous among all the Argives and win the glory of valour” (Iliad, Lattimore, Book 5). So opens the aristeia. Homer shows Diomedes seething through the ranks: “but you could not have told on which side Tydeus’ son was fighting.” He is like a “winter-swollen river” that exceeds the confines of the dikes and destroys “the many lovely works of the young men [that] crumble beneath it.” Even when Pandarus strikes him in the shoulder with an arrow, he is undaunted, crying out to Athena: “if ever before in kindliness you stood by my father through the terror of fighting, be my friend now also.” Athena heeds his prayer and lifts the veil from his sight so he can see the gods on the battlefield. She warns him not to engage the immortals, except Aphrodite: “her at least you may stab with the sharp bronze.”

Fighting continues. Diomedes slaughters Trojans and nearly kills Aeneas until Aphrodite intervenes to carry her son from the field. Outraged, Diomedes pursues her: “Now as, following her through the thick crowd, he caught her, lunging, [he] made a thrust against the soft hand with the bronze spear… and blood immortal flowed from the goddess.” Aphrodite shrieks and drops Aeneas. Apollo takes him up, and Diomedes has the temerity to press the attack “though he saw how Apollo himself held his hands over [Aeneas].” Three times Diomedes assaults the god’s protection and three times is rebuffed, until Apollo warns him: “Take care, give back, son of Tydeus, and strive no longer to make yourself like the gods.” Diomedes yields but “only a little.”

Apollo then calls on Ares to halt this mortal who has become too dangerous. Ares enters the fight beside Hector, “made play in his hands with the spear gigantic,” and the balance of the battle swings violently. Diomedes, still seeing the gods, warns: “Friends… there goes ever some god beside [Hector]… Ares goes with him.” With Ares in the line, Hector ravages through the Greeks until Hera protests the slaughter and Athena, cool, sly, and tactical, asks Zeus whether she may drive Ares out with “painful strokes.” Zeus accedes. Athena goes directly to Diomedes, reminds him of her support for his father, and assures him: “no longer be thus afraid of Ares… such a helper shall I be standing beside you.” She takes control of his chariot and drives Diomedes straight at the war god. Ares lunges; Athena directs the spear aside and she leans behind Diomedes’ thrust and guides it “into the depth of the belly where the war belt girt him.” Ares bellows “with a sound as great as nine thousand men make, or ten thousand.”

What makes Book Five useful is that it’s diagnostic. Homer shows us what happens when a moment is so narrow and so structurally correct that the impossible becomes briefly possible. Diomedes doesn’t “beat” Aphrodite or Ares in any modern sense. He doesn’t outclass them, and Homer goes out of his way to make that clear (Apollo stops him cold). His wounding Ares is a triumph of alignment: Athena clears perception, defines the boundary, grants permission, and then physically guides the point. In other words, the feat is not raw violence. It is violence delivered at the exact instant the encounter becomes bindable. The Greeks called it kairos: the right moment as a real opening that exists only when the world’s geometry allows it.[1]

I read ki-musubi into this mythopoetic framing. Homer knew the agency of Athena provided the framework of potential, but the actions all had to crystalize appropriately. Each participant had their role and had to play it correctly. This is where the potential of ki-musubi and Aikido becomes more honest. The goal isn’t “blending” or “harmonizing” in a soft, therapeutic sense. The goal is to create the moment when the encounter is tied so that two bodies stop being two independent systems and become one shared constraint. When the axis is established, the opponent’s options collapse not because you are stronger, but because the structure no longer permits escape without cost. Timing, then, isn’t “speed.” It’s not even initiative in the aggressive sense. It’s the ability to enter at the instant the opponent’s intention has fixed. When the line becomes predictable, when the door is briefly open, when the technique is no longer a choice but the only coherent outcome. Diomedes is a mythic diagram of that principle: not “man wounds god,” but “a moment arrives in which the strike becomes inevitable.”

Kairos (καιρός) is a descriptive Greek term meaning the right moment: the critical opening; the decisive “now.” Philologically, it carries a semantic range that includes a critical point, due measure, and even a kind of vulnerable seam. Later Greek writers apply it to rhetoric, medicine, and ethics: the right dosage, the right word, the right intervention. But the underlying structure is consistent: there exists a moment when the situation becomes actionable; outside that moment, action becomes waste. The “right time” is not abstract time. It is situational time.

I selected Diomedes because it is one of the most dramatic encounters, but, honestly, it is almost too supernatural. The agency and actions of the gods, Athena specifically, I read not as divine intervention but rather as a means to emphasize how spectacularly important those moments are. They exist as if the intervention of a deity is required. Thus an interpretive extension of kairos as “a deed normally beyond your innate ability” that kind of “one chance to do the impossible.”

But kairos is the opening as a whole: the opponent’s intent, posture, balance, attention, commitment, environment, your position, your readiness, and the moral/psychological permission to act all converging into a brief window where action becomes inevitable if you’re competent. Thus, almost any combat scene in the Illiad provides descriptions of kairos: heroes wait for their opponent’s weight to shift, they exploit overreach or fixity of position.

These combat realities are difficult to describe but many of the men in Homer’s audience would have had direct combat experience. Much like contemporaries of George Silver, Munenori and Musashi, the audience viscerally knew what the author was trying to capture.

As we explored in the earlier post, in Japanese combative theory, sen is usually taught as “initiative,” but initiative is also a slippery modern word. Merging lexicons clarifies the martial point. In Japanese combative theory, sen is often taught as “initiative,” but properly understood it is your relationship to the opponent’s action-cycle: acting before the opponent’s intent fully manifests, entering as it begins, or responding after commitment. Most students read these as timing categories. A better way to read them is as strategies for manufacturing or exploiting kairos. Kairos is the opening. Sen is how you arrive there. And when you succeed, when the encounter ties and becomes one system under constraint centered on an axis, that is what Aikido names as ki-musubi.

_________________________

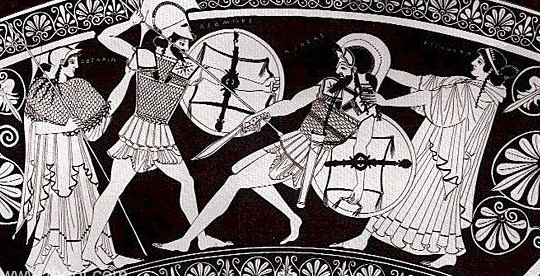

Banner image is the Duel of Diomedes and Aeneas from an Attic Red Figure Calyx ca 490 BCE in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

[1] The Wikipedia entry prefers the framing of kairos as it pertains to archery and weaving, in the sense of a timed entry into an opening, which is adjacent to the earliest extant instance where καιρός appears as a noun meaning a “right or proper time” and is generally traced to Hesiod (8th–7th century BCE) in Works and Days. Although its meaning there is still developing (more “fitting time” than the rich purposeful sense it will later take), it’s the first literary occurrence in that abstract sense. In Homeric epic, the noun καιρός in the sense of a decisive time-moment does not appear; instead, a related adjectival form (καιρίος / kairios, meaning something like “fatal” or “critical”) and καίριον as a vulnerable spot on the body does occur in Homeric poetry. This usage refers to a critical location that, if struck, can be fatal; a “critical point” in space rather than a moment in time. This spatial sense connects to the later metaphorical sense of an “opening” or opportunity. A rich exploration is Kairos as a Figuration of Time by Dietrich Boschung, 2013.

In archery, kairos maps cleanly to archery as “the right moment to release.” (And very reminiscent of what I recall from Zen in the Art of Archery by Eugen Herrigel). Kairos can be framed as the moment when the shot must be released because the conditions have converged. It’s not “time” in the neutral sense (chronos), but time as the instant when alignment, draw, aim, breath, and target relationship become true. You don’t “decide” to shoot as much as you recognize when the system has become shootable. Outside that window, release becomes either premature (you confess your intent and miss) or late (you chase a moment that has already passed).

The philological thread becomes richer when the language of aim and timing crosses into the moral domain. When Ecclesiastes 3:1 (“To everything there is a season…”) was translated into Greek in the Septuagint, the translator paired καιρὸς (kairos) alongside χρόνος (chronos). In that line:

τοῖς πᾶσιν χρόνος, καὶ καιρὸς τῷ παντὶ πράγματι

For everything there is chronos, and kairos for every matter under heaven.

Chronos marks ordinary duration; kairos marks the appointed or fitting moment when a particular action becomes right. The distinction is not merely semantic. It implies that the world is not composed of identical minutes, but of moments with different moral weights: times when action is not only possible, but demanded.

This archery logic returns, unexpectedly, in the language of failure. The primary New Testament Greek term for “sin” is ἁμαρτία (hamartia), derived from a verb meaning to miss the mark, fail, or err, a word that can carry the image of a thrown spear or loosed arrow that does not land true. The point is not that moral failure is a technical mistake, but that the metaphor is structurally exact: there is a target, there is a right line, and there is a moment when action must be taken correctly. In that sense, kairos and hamartia describe opposite ends of the same geometry: the opening in which the shot becomes true, and the failure that occurs when it is loosed outside the conditions that make it real.