Theseus enters the world where the gods themselves have failed to agree.

Athens belongs to Athena by decree, but not by consent. She gives the city the olive; Poseidon strikes the rock and leaves salt, horses, and tremor behind. The contest is decided, yet unresolved. The city will bear Athena’s name, but Poseidon does not withdraw. He remains deep. In earthquakes, in the memory of violence that comes from the sea.

Theseus is born from that remainder.

He has two fathers. One is civic and named; the other is elemental and undeniable. Aegeus leaves a sword and sandals beneath a stone and departs, deferring recognition. Poseidon does not depart at all. His presence enfolds the earth.

Athens had already claimed a deeper origin. Before gods and kings, the city insists it rose from the soil itself: snake-bodied kings, born from earth, autochthonous. Cecrops coils beneath the Acropolis. Erechtheus follows. This is the city Athena protects: old, rooted, suspicious of newcomers. Even heroic ones.

Theseus does not belong to this lineage. He is not born from the ground. He is introduced.

The Greeks understand this arrangement. Authority must be recognized, not inherited; demonstrated, not proclaimed. Theseus’ task is not to reconcile gods or bloodlines, but to demonstrate his excellence.

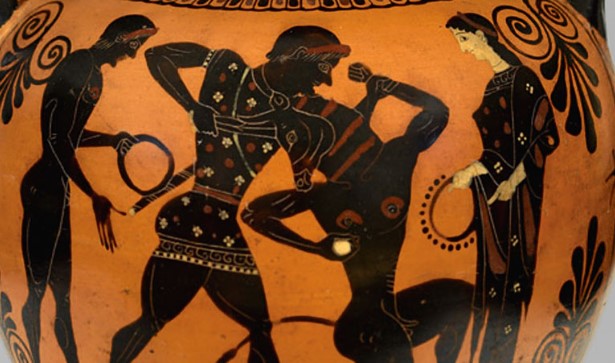

When the time comes, Theseus does not take the safe road by sea. He chooses the land route to Athens, and in doing so invents a new kind of heroism. Each figure he encounters is a rule made excess. These men enforce customs that distort proportion: hospitality as extortion, strength as entitlement, measure as cruelty. Theseus kills them by exact reversal. He does not overwhelm; he corrects.

The Greeks notice. This is not a hero who clears the world. This is a hero who calibrates it. Heracles’ labors had already done the clearing. Theseus arrives after, like a surveyor walking through land that has been made habitable but not yet livable.

When Theseus reaches Athens, no one recognizes him. Aegeus nearly poisons him. Recognition comes late, almost by accident. It will always be this way with Theseus: acknowledgment follows action.

Crete comes next. The Minotaur is a civic embarrassment. Theseus arrives not as champion but as solution. He does not fight blindly; he takes a thread. The Greeks understood that violence guided by technique is different from violence guided by rage. The labyrinth is not defeated by strength but by proper orientation.

But orientation requires memory.

Theseus leaves Ariadne behind. He forgets her on Naxos. The act is smaller than betrayal and therefore more dangerous. The Greeks had seen this before. Oeneus, grandfather of Diomedes, forgets Artemis when the gods are honored, and the Calydonian boar follows. Forgetting is never neutral. It invites the god who was omitted.

On the return voyage, Theseus forgets again. This time, the sails.

Aegeus throws himself into the sea. The city gains a king by losing one. The Greeks pause here. This is not triumph. It is cost without intention. Theseus does not seize power; it arrives as consequence. A kingship born of forgetfulness already carries its limit within it.

As king, Theseus performs his most unheroic act: he unifies Attica. No monster, no duel, no riddle. Just villages gathered into one polis. This act cannot be sung easily. It requires administration, consent, and delay. So the Greeks attach it to Theseus and move on.

It is at this point that Athens quietly adjusts the calendar. Theseus is made contemporary with Heracles. They hunt together. They descend into the Underworld together. This pairing is not ancient; it is convenient. Athens needs a hero who can stand beside the only hero every Greek recognizes. Theseus is elevated not because he demands it, but because the city requires it.

Yet even here, the difference remains. When Theseus and Pirithous sit in the Underworld and mistake hospitality for entitlement, it is Heracles who returns to pull Theseus free. Pirithous remains; along with a portion of Theseus’ buttocks, a just-so story explaining why Athenian boys are lean where others are not. Even rescue leaves a mark.

Then come the abductions. Antiope. Helen. Theseus begins to behave like a hero long after he has become a ruler. He mistakes heroic license for civic right. The Dioscuri undo his seizure of Helen with embarrassing efficiency. The old economy – eye for eye, sister for mother – reasserts itself. Athens does not intervene. The city watches.

From here, Theseus begins to drift. His marriage to Phaedra turns catastrophe inward. His sons turn against him. His authority erodes not through rebellion but through neglect. Forgetting now runs both ways.

Eventually, he leaves Athens. No trial. No decree. Just absence.

He dies on Skyros, pushed from a cliff by a king who no longer needs him. There is no lament in Homer. Athens does not call him back until much later, when his bones are retrieved and installed as relics. The city will honor him safely once he can no longer rule.

This is how the Greeks used Theseus.

They did not make him a founder; that honor belonged to the earth itself. They did not make him an immortal; Olympus had no seat for a hero who forgot. They made him a bridge between village and polis, between heroic violence and civic order, between the age of monsters and the age of law.

_________________

The contest between Athena and Poseidon was preserved as architectural and cultic fact. On the Acropolis, within the later Erechtheion, ancient Athenians pointed to a saltwater fissure or well, known as the Erechtheis thalassa (“the sea of Erechtheus”), which they identified as the physical trace of Poseidon’s trident strike (Pausanias, Description of Greece 1.26.5). During storms or earthquakes, the well was said to echo with the sound of waves, reinforcing Poseidon’s continuing presence beneath the city.

Crucially, this salt spring was not removed, purified, or repurposed after Athena’s victory. It was enclosed. The Erechtheion itself was constructed as a compromise temple, housing Athena’s olive tree, Poseidon’s salt sea, and the cult of Erechtheus under a single roof. This architectural solution mirrors the theological one: Athena rules, but Poseidon remains.

Erechtheus provides the genealogical hinge. He is both an autochthonous king, sometimes identified directly with the earth-born serpent line, and, in certain traditions, a figure fused with Poseidon himself (Apollodorus, Library 3.14.8). The salt spring named for him thus binds together earth, sea, and kingship, encoding Athens’ claim that its sovereignty emerges from soil yet remains exposed to chthonic and maritime forces it cannot fully master.

This unresolved divine settlement matters for the myth of Theseus. He is the human remainder of a divine stalemate. Athena provides Athens with law, craft, and continuity. Poseidon leaves behind rupture, horses, earthquakes; and, in Theseus, a son who will never quite belong to the snake-born city he serves. The Acropolis itself already contains the problem Theseus embodies: a polity founded on order that permanently encloses what it cannot assimilate.

Athens distinguishes itself among Greek poleis by claiming autochthony; the belief that its earliest kings arose directly from the soil of Attica rather than through migration or conquest. Athens is one of the very few poleis to claim autochthony, and the only one to convert it into a comprehensive civic ideology rather than a local origin tale. (Thebes and the myth of the Spartoi is the only other major polis to assert indigenous status.) Cecrops, half-man and half-serpent, and Erechtheus embody this claim (Herodotus, Histories 8.44; Apollodorus, Library 3.14.1). This ideology renders Athens unusually suspicious of external founders and heroic newcomers. Theseus, whose lineage is mixed and whose authority must be demonstrated rather than inherited, enters a city that ideologically prefers kings who are born rather than introduced.

The tradition consistently gives Theseus dual paternity: he is the son of Aegeus, king of Athens, and also of Poseidon. The tokens Aegeus leaves beneath the stone (the sword and sandals) function as instruments of recognition (Plutarch, Life of Theseus 3–6). The ambiguity serves a civic function: legitimacy must be proven publicly. Theseus’ excellence precedes his acknowledgment, a pattern that will recur throughout his life.

The so-called “road labors” of Theseus are preserved most fully in Plutarch and Apollodorus (Plutarch, Theseus 8–11; Apollodorus, Epitome 1.1–1.24). Unlike Heracles’ labors, which clear monsters from the world, Theseus’ acts correct social perversions. Each antagonist enforces a distorted rule: hospitality becomes extortion, strength becomes license, measurement becomes cruelty. Theseus kills each by imposing upon them the very rule they misuse. Ancient commentators already recognized this as a distinctively civic form of heroism.

When Theseus reaches Athens, he is nearly poisoned by Medea before Aegeus recognizes him by the tokens (Plutarch, Theseus 12). Recognition comes late and accidentally. This episode establishes a recurring pattern: Theseus is acknowledged only after action, never in advance. The myth mirrors Athenian political culture, in which authority is provisional and subject to proof.

The Cretan episode presents the Minotaur not as a wild beast but as a political failure: a monstrous outcome of Minos’ broken vow to Poseidon (Apollodorus, Library 3.1.3–4). Theseus’ victory depends not on strength but on techne, expressed as Ariadne’s thread. Greek authors repeatedly emphasize that the labyrinth is defeated by orientation rather than force. This distinction becomes crucial for what follows.

Theseus abandons Ariadne on Naxos. The Roman poet Catullus captures her mournful disbelief:

For looking forth from Dia’s beach, resounding with crashing of breakers, Ariadne watches Theseus moving from sight with his swift fleet, her heart swelling with raging passion, and she does not yet believe she sees what she sees, as, newly-awakened from her deceptive sleep, she perceives herself, deserted and woeful, on the lonely shore.

Catullus 64

Early sources have her slain by Artemis for having seen Dionysus (Homer, Odyssey 11.321–325). The later versions attribute her abandonment to divine command by Dionysus or Athena, others to Theseus himself (Hesiod fr. 147 MW; Plutarch, Theseus 20; Vase paintings make it a command from Athena). In either case, Ariadne is later discovered and married by Dionysus, and her crown is set among the stars, the Corona Borealis (Ovid, Metamorphoses 8.176–182). Greek myth does not treat forgetting as neutral. The narrative logic aligns Theseus’ lapse with earlier myths of ritual omission, most notably Oeneus, whose failure to honor Artemis brings the Calydonian Boar (Apollodorus, Library 1.8.2).

On his return, Theseus forgets to change the black sails to white, the signal agreed upon with Aegeus. Seeing the black sails, Aegeus throws himself into the sea (Plutarch, Theseus 22). Theseus thus becomes king not by intention or revolt, but by consequence. Greek authors linger over this detail: kingship born of negligence is already compromised.

Theseus’ unification of Attica (synoikismos) is preserved primarily in later historiographic and biographical sources (Plutarch, Theseus 24–25). Unlike monster-slaying, this act requires negotiation, consent, and institutional patience. It lacks the narrative drama of heroic myth, which may explain why later tradition quickly moves past it even while crediting Theseus with the deed.

Athens later synchronizes Theseus with Heracles, making them companions in the Calydonian Boar Hunt and the descent to the Underworld (Plutarch, Theseus 7, 30). This pairing is not early Homeric tradition but a deliberate Athenian elevation, allowing Theseus to stand beside the only universally recognized Greek hero.

When Theseus and Pirithous attempt to abduct Persephone, they violate divine hospitality. Heracles rescues Theseus, but Pirithous remains bound forever (Apollodorus, Epitome 1.23; Plutarch, Theseus 31). Comic aetiologies explaining Theseus’ partial immobility appear later, but the moral point is clear: even when saved, Theseus is marked.

Theseus’ abductions, first of Antiope, then of Helen, mark a shift from civic hero to overreaching ruler. Helen’s brothers, the Dioscuri, invade Attica, recover their sister, and carry off Aethra in exchange (Apollodorus, Library 3.10.7). The episode resolves through equivalence, not adjudication, signaling a reversion to older moral economies. Athens does not defend Theseus.

After the catastrophe of Phaedra and the death of Hippolytus (Seneca, Phaedra; Pausanias Description of Greece1.22.2), Theseus’ authority collapses. He leaves Athens without formal trial and dies on Skyros, pushed from a cliff by King Lycomedes (Plutarch, Theseus 35). Homer offers no lament. Only later does Athens retrieve Theseus’ bones and install them in a hero shrine, honoring him safely once he can no longer rule (Plutarch, Theseus 36).

The sources consistently show that Theseus is not a founder, not an immortal, and not a tragic hero in the Homeric sense. He is instead a transitional figure, used by Athens to bridge heroic violence and civic order. His repeated failures of memory are not incidental. In Greek myth, forgetting is never passive; it is an ethical lapse with consequence.

One thought on “Theseus”