In most tellings, the Labors come later. Heroic, impossible tasks imposed to atone for the uncleansable act of killing his own children. Violence precedes expiation. Crime is answered by ordeal.

Euripides reverses the order. The Labors come first, to prove that achievement is no protection.

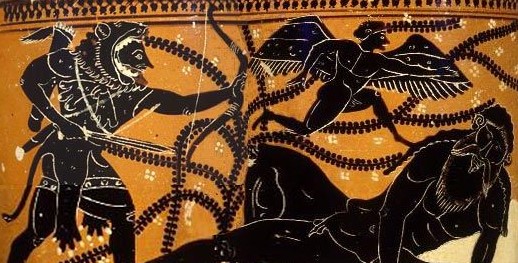

The monsters are dead. The roads are passable again. The world, which required Heracles’ violence, has been satisfied. The Nemean lion no longer stalks the hills. The Hydra is cauterized. The Augean rot has been flushed from the land. Even death has been visited and returned from.

Procedural Eurystheus, that small man propped up by law and divine timing, no longer holds dominion over him. The term of humiliation has ended. The tasks are complete.

Heracles arrives at Thebes not as the son of Zeus, but as a man restored to human scale:

husband, father, supplicant who has done everything required.

That is when Hera acts.

Not earlier, when he strangled lions or scoured the earth of rot. Not when his body was still an instrument shaped for excess. She waits until he has crossed back into domestic life, into lineage, into continuity.

Heracles: the Glory of Hera. The name does nothing to appease her. It sharpens the insult. His existence remains a standing violation of her domain: marriage, legitimacy, lawful succession.

So she sends Lyssa, Madness herself.

Lyssa hesitates.

She is not eager to infect. She knows Heracles has honored the gods. She knows this excess is Hera’s. But excess is what gods use when proportion no longer suffices.

Heracles does not rage at first. He mis-sees.

The house becomes a battlefield. The thresholds dissolve. Walls open into open ground. There are no structural limits. His very children become enemies. Eurystheus, always Eurystheus, stands where his sons stand. Heracles acts as he always has: decisively, without doubt. Euripides adds Megara to the body count. One more to make the the killings complete. No residue of the life Heracles returned to is permitted to survive.

Athena intervenes late. She lifts the madness. The weapon falls. Silence enters the house. Heracles stands among corpses he recognizes.

Madness for the Greeks is no defense. No argument. No theology that helps. Heracles curses existence itself, curses the structure capable of producing such symmetry. He wants to die not to escape the tragedy, but to correct it. Suicide would restore balance: destroyer destroyed.

Theseus interrupts. With friendship.

Theseus, who has already overreached. He has already abducted Helen, descended to the underworld, sat trapped in forgetfulness until Heracles himself tore him free. A hero already cracked like an amphora, already indebted.

He does not judge.

He does not cleanse.

He stays.

He simply refuses to let Heracles be alone with what he has done.

No god resolves the crime. No court absorbs it. What interrupts annihilation is not law or ritual, but friendship. One ruined man sitting beside another, insisting on endurance without consolation.

Purification will come later. Exile will come later. First comes recognition of the act. Accepting the impossibility of a return.

____________________

What’s in a name? “Heracles” (Ἡρακλῆς) is the cruel joke. Hēraklēs breaks down as: Hēra (Ἥρα) + kléos (κλέος) glory, fame, renown – thus, The Glory of Hera.

Two ancient logics attach to the name, both unsettling.

The first is appeasement. The child is named as an offering: this one exists for your glory. It fails immediately. Names do not tame gods.

The second logic is theodical, and more disturbing. Without her hatred, there is no hero. The Labors, the ordeals, the suffering are the engines of kleos. Heracles achieves glory through Hera’s persecution.

Heracles is the greatest of Zeus’ sons, and therefore the greatest affront to Hera. Zeus is the divine adulterer; Hera is the guardian of lawful order, of marriage, lineage, succession. Every illegitimate son violates her jurisdiction. Heracles violates it spectacularly. Zeus loves him most. So Hera persecutes him relentlessly, patiently, strategically.

That strategy culminates in Eurystheus.

Eurystheus is Heracles’ cousin, legal superior, and ritual master. A petty bureaucrat placed over a great one by Hera’s cunning. Both descend from Perseus, the Perseid line. Hera engineers the timing of births so that Eurystheus is born first, activating Zeus’ own oath that the next Perseid born will rule Mycenae. Zeus binds himself. Hera collects.

The result is precise and humiliating: the strongest man alive must obey the weakest king alive.

The Greeks understood that authority does not require excellence; it requires procedure. Eurystheus is therefore not Heracles’ rival in any heroic sense. He is his legal superior and ritual master. A figure of lawful precedence installed by Hera’s manipulation of genealogy and timing. Through Zeus’ own oath, the Perseid born first would rule Mycenae. Zeus binds himself; Hera enforces the consequence. The result is exact and humiliating: the strongest man alive must obey the weakest king alive.

Eurystheus dictates and presides over the Labors; the twelve years of service decreed by Delphi as the condition for cleansing Heracles’ pollution (Apollodorus, Library 2.4.12). The Labors are not adventures but imposed servitude, governed by procedural judgment rather than merit. In this sense, Eurystheus anticipates a truth the Greeks already grasped intuitively: authority operates independently of excellence, even in a heroic age.

It is against this inherited framework that Euripides makes his decisive inversion.

In older tellings, Heracles’ madness comes first and the Labors follow: ordeal as expiation, suffering as corrective. Euripides reverses the order. The Labors come first, to demonstrate that achievement offers no protection. The world has already been saved. The monsters are dead. The roads are open. Eurystheus’ authority has expired. Heracles returns to Thebes complete; restored to domestic life and civic identity.

When Hera acts at this moment, the catastrophe that follows cannot be understood as punishment in any ordinary sense. It is structural annihilation. Violence that had been sanctioned, rewarded, and celebrated proves incapable of being contained once its instrumental purpose has been fulfilled. Excess turns inward. The same force that preserved order destroys it.

The radical nature of this reversal becomes clear when Euripides’ Heracles is set beside Philoctetes by Sophocles. Sophocles stages a sharp ethical dilemma without easy answers: the war needs Philoctetes, but Neoptolemus’s sense of honor recoils at Odysseus’ coercion and lies. When Neoptolemus returns Philoctetes’ bow and confesses, Philoctetes refuses to sail to Troy. Heracles appears (post apotheosis) in his divine form to command Philoctetes to go, where he will be healed and win glory. The play’s deus ex machina ending, obedience to a divine command rather than reconciliation among men, suggests Sophocles’ skepticism that politics alone can heal moral wounds. Yet Sophocles insists on a moral economy that ultimately balances. Still believes that truth can heal.

Euripides writes after that confidence has collapsed.

Heracles was produced in 416 BCE, during the late, corrosive phase of the Peloponnesian War. In that same year, Athens articulates its position with brutal clarity in the Melian Dialogue: justice applies only among equals; necessity governs the rest. It is history’s coldest articulation of might makes right.

This is where Euripides converges with Thucydides. Herodotus had shown how Greece unified to resist tyranny. Thucydides records how democratic Athens becomes the tyrant. A tyrant worse than Persians, Athens is methodical, rational, confident, and increasingly blind to moral consequence. The war differs from earlier Greek conflicts in scale, duration, and totality. It corrodes language, erodes restraint, and transforms success into justification rather than responsibility. Victory no longer civilizes. Power no longer ennobles; it consumes.

Euripides stages the same diagnosis in mythic form.

Like Heracles, the strongest and most victorious of heroes, Athens proves incapable of protecting what matters most. The city that once liberated others becomes their destroyer. Melos is wiped out; its population erased. The act is justified as necessity. Confidence in power substitutes for moral vision. The system fails from within.

Significantly, Heracles offers no restorative closure. No god resolves the crime. Athena halts the violence but does not justify it. There is no tribunal, no epiphany, no reintegration into a renewed moral order. Heracles’ excellence does not redeem him. His suffering does not instruct. Nothing about the catastrophe is rendered meaningful.

Sophocles and Euripides overlapped for decades, but they wrote from different phases of Athenian moral life. Sophocles offered tragic nobility: a civic vision in which intelligence, courage, and culture conferred legitimacy, and in which suffering educated the polis toward order. Euripides issues a bleaker warning: suffering may teach nothing, and order itself may have failed.

Yet Euripides does not leave his audience with nihilism. He refuses to sermonize, but the lesson is unmistakable. Heracles saves the household from a tyrant and then annihilates it himself. The same logic applies to political actors whose hubris is narrated as necessity. Athens is a liberator turned destroyer, confident in the righteousness of its actions and blind to their consequences.

What remains, finally, is not law, power, or virtue, but human solidarity. Theseus does not purify Heracles. He remains with him. He refuses isolation as the final consequence of excess. If the gods are unreliable, justice unstable, and excellence insufficient, then survival depends on the capacity to acknowledge the consequences of one’s own strength.

Athens, Euripides suggests, may not be able to save itself through triumph, rationality, or institutional order alone. But it might yet endure if it can learn to sit with what it has done and to recognize itself in those who have acted on its behalf.

And there is a final human sentiment: Euripides ends his play with Heracles mourning,

The man who would prefer great wealth or strength more than love, more than friends, is diseased of soul

Euripides, Heracles, trans. William Arrowsmith

To which the closing chorus enjoins,

We go in grief, we go in tears, who lose in you our greatest friend.

Twelve years after the play is produced, the Athenian fleet is annihilated. The Spartans are victorious. But no one wins.

One thought on “Heracles”