This morning was a focus on the basic sinawali pattern at first merely to learn the drill. There are numerous online references to help remind you of the basic pattern. YouTube is an amazing resource if you can discern the true from the false. Techniques and tricks that once were only taught in person and at seminars that required travel and treasure to get to, are now posted and feely available. Knowledge for free! But it still requires a critical eye to steal the techniques and learn the skills. And that takes dedicated training – there is no real substitute for hands on instruction.

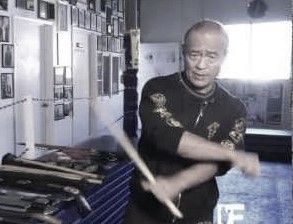

Nevertheless, to provide some direction, your search would be well served by starting with Guros Presas and Inosanto.

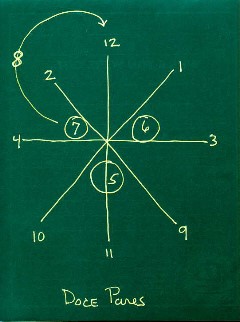

I would also point you to James A Keating and this very useful article from Pete Kautz, where he provides a ‘sinawali mapping’ tool. Good mental aids to facilitate your learning and better comprehension.

To help translate body patterns Aikidoists already know, I likened the start of the pattern to hasso. Starting in migi-hanmi hasso, one holds both weapons (double stick, dagger, whatever) – but rather than a 2-hands on one (katana), we are holding one weapon in each hand: two hands are weaponized rather than 2 hands on one weapon. From the chambered position, the top hand begins the fore-hand (i.e. thumb up grip) yokomen, followed by back-hand (ie thumb down) gyaku yokomen, and then the initiating hand again from the cross body start (back-handed) which then returns to the low chamber so the sequence can begin again from the left. I will not get overly descriptive since visual aids are readily available. In short, there is a 3-beat striking pattern, with the return to low chamber akin to sheathing the sword, or stabbing an opponent to your rear as a 4th beat. But that is merely my pedagogical metaphor. It is a simple ‘as if’ to get the pattern ingrained. As it is typically presented it is three strikes starting top chamber fore-hand, then three strikes starting with the fore-hand from the opposite side. The beginning ‘beats’ will sound like a waltz – one, two, three, one, two, three…. but that is just a learning pace.

The strikes for our purposes were yokomen/yokomen/gyaku-yokomen (in the doce pares numbering 1/1/2).

Recognize that this is an “Aikidification” of a Spanish/FMA system, so please understand that it is a translation – a means of better understanding a universal pattern. Once the basic pattern is mastered, it is time to enhance the flow.

The ‘weaving’ pattern of sinawali manifests as soon as the 3-beat pattern is connected on each side – suddenly the waltz box-step rhythm becomes an enchanting ‘flower’ woven in front of your opponent. For the uninitiated it dazzles and overwhelms precisely because the linked strikes do not stop. We have now created an endless looping series of strikes that describe the horizontal figure-eight (infinity)! Where have you executed this before? With the jo: our “warm up” of the rotating hand over hand exchange is precisely the same idea – just executed (again) with a two-handed weapon. But look beyond the simple tool in your hand – get beyond the simple instantiation of the specific and start to perceive the broader patterns. Now ask why hasn’t that “warm up” exercise ever been presented to you in its proper light for what it is?

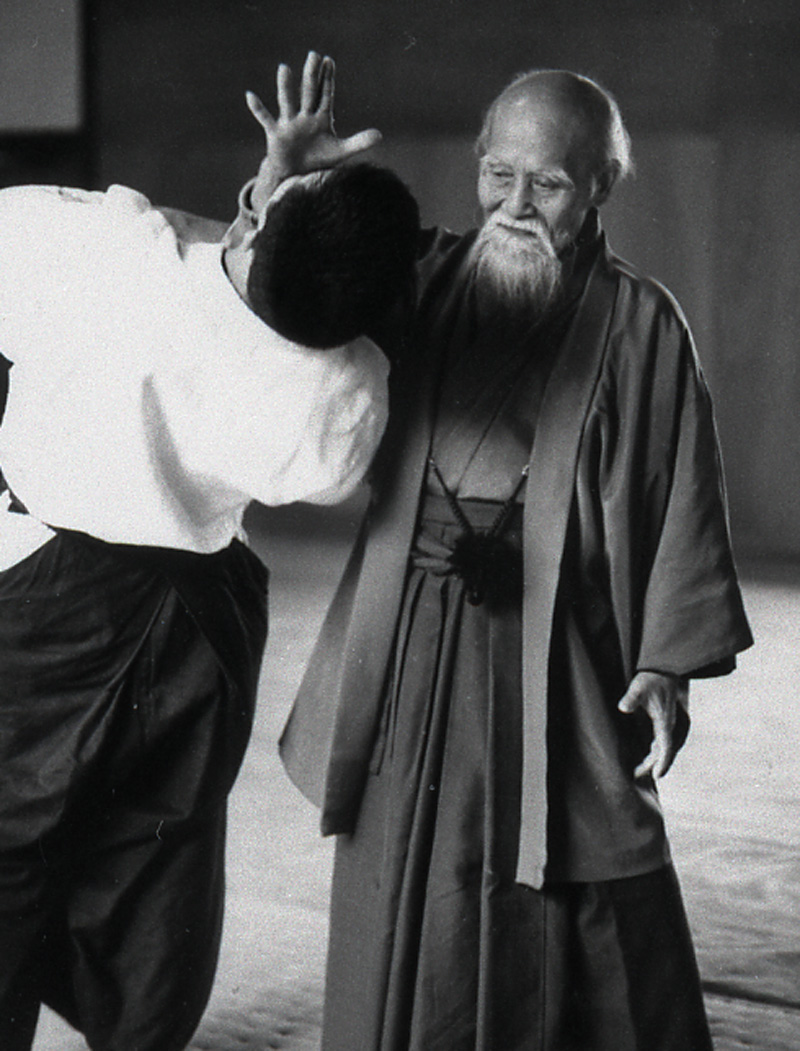

With growing confidence and patterns flowing, we added the footwork – and with the reminder that the beginner’s line is on the 180 degree (face to face) – but we should quickly learn to move past because this is a combative pattern. Start to flank your opponent – move to the 90 degree – when both players start to move suddenly you will look like cats – true predators sizing each other up. Search for Paul Vunak as visual inspiration. If you were fortunate enough to train with him, Chiba Sensei broke the relatively static 180 degree formula of Aiki-weapons. His systematic exploration and development lead to his creation of the Sansho series, which when presented correctly is an encircling kumi-jo. [1]

Having covered the basic pattern, added flow and footwork, made the cognitive connections back to Aikido’s forms – we then played with tools of various lengths (shoto to tanto) only to remind ourselves of a generalization that the longer the weapon the fewer joints can be used to wield it. Simple examples, two-handed kata is manipulated primarily from the shoulder (as opposed to the elbow or wrists), whereas a dagger is fluidly deployed with the wrist alone. This is not axiomatic, but rather a reminder that smaller weapons are ‘faster’ because multiple joints can impel them along vectors that can change rapidly.

Shorter weapons, closer range, less reactionary windows, faster response time necessary. Suddenly the axioms of strike whatever moves first, is closest to you become real – no longer conceptual. The FMA nomenclature of largo mano, sumbrada, and hubud ranges is useful (effectively long range – where the weapon only is deployed; short range – where the weapon and checking hand is used; and trapping range – where all elements are in play).

Some global reminders lest we forget the purpose of training: strike hands not weapons (we dont trade blows except in training), always press – fill voids (you cannot win by defending), in a knife fight there are no primary attacks (deceit and tricks rule; stop the one-hit one-kill mentality), never forget every slash can be delivered as a thrust.

We then dropped back to a single-stick to clearly articulate how a pattern becomes combat effective. The first bunkai from the initiating fore-hand strike: the yokomen to yokomen weapon contact now will ‘flow’ past the stop-hit so that tori’s weapon rides around uke’s so as to strike the opposite side of uke’s head. The yokomen to yokomen is no longer primary, rather tori rides uke’s energy to deliver a gyaku-yokomen (think chuburi), then pick up uke’s weapon hand with the pommel (punyo). Now with the contact with the top hand (still holding the weapon) executes nikkyo. Suddenly the true power of nikkyo is revealed – with correct and precise form – tori will disarm and simultaneously cut uke’s wrist using the edge whilst disarming uke with tori’s forearm against the flat of uke’s blade. This is best experienced in person to feel the application of leverage. Physics works but the experience of it is for the dojo.

_____________________________

[1] Recall that as late as 1989 Chiba Sensei was still working through the “basic” jo forms – and sansho was introduced a few years later.