Chris Mulligan sensei sent me the draft format of this article in February 2020 for a quick review. His article makes explicit how he connects language acquisition with teaching and learning Aikido; which I have referenced numerous times in earlier posts. The published version is copied in full below.

______________

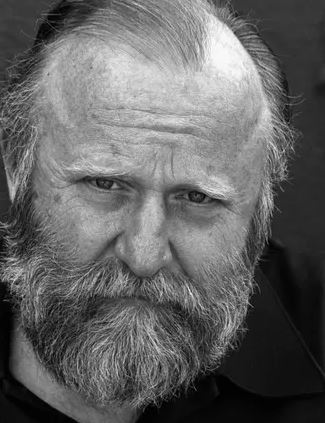

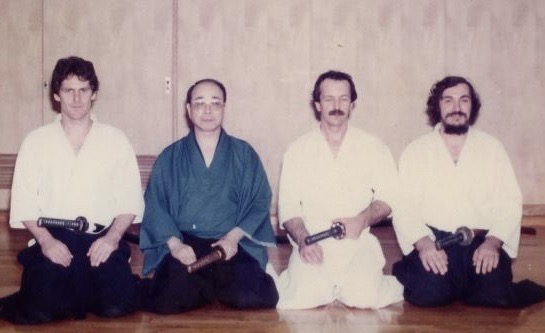

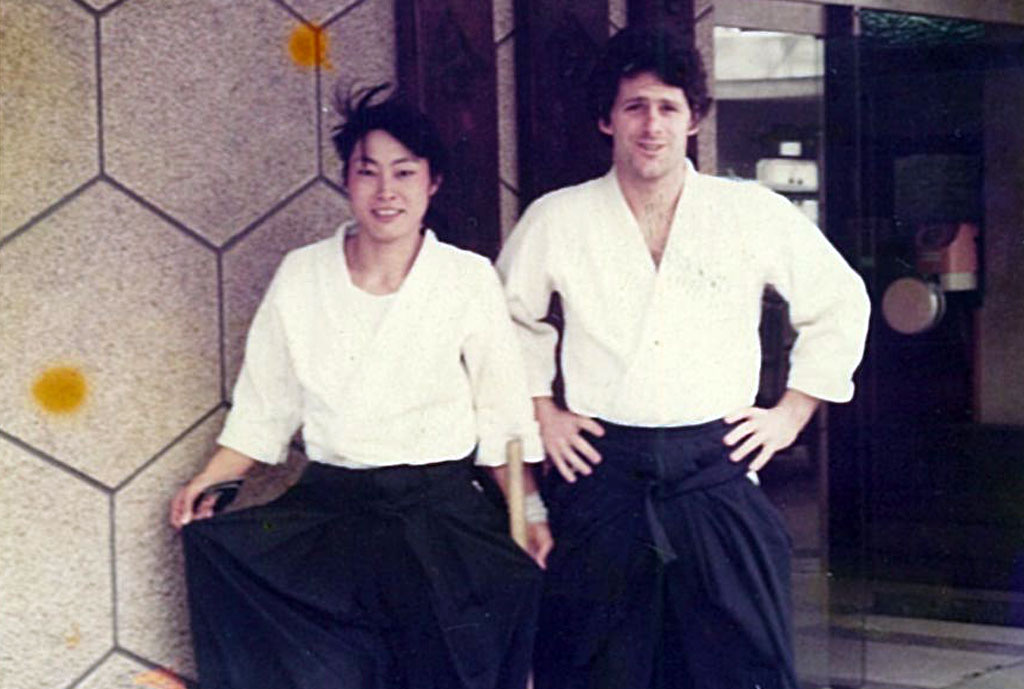

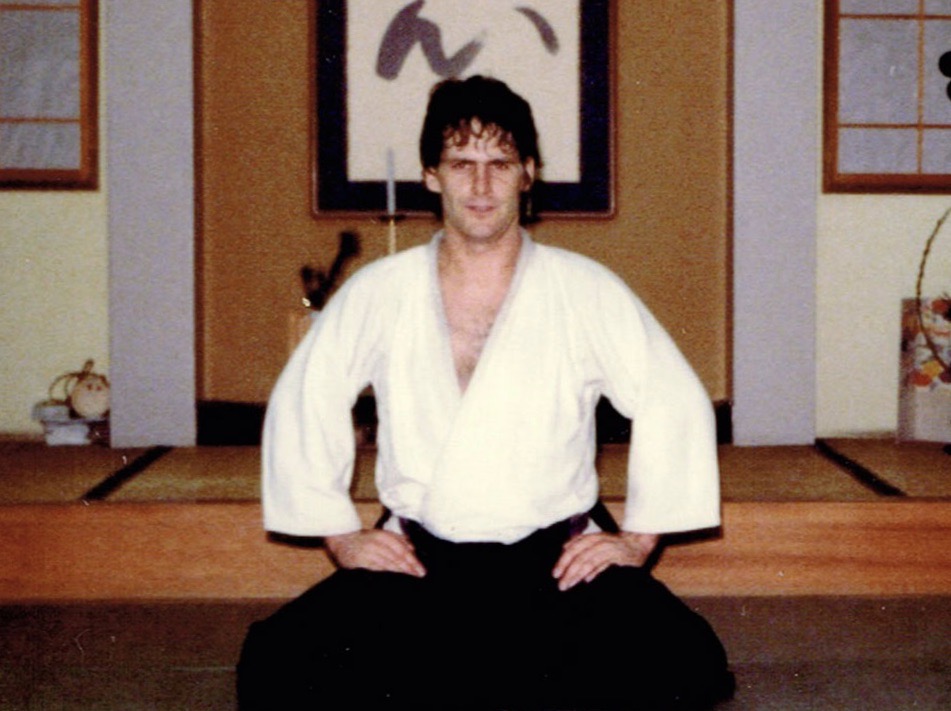

Christopher Mulligan Sensei began studying Aikido in 1974. He spent 11 years in Japan studying mostly at the Hombu dojo in Tokyo. Chris, along with Yoko Okamoto Sensei, established Portland Aikikai in 1993. Since returning to Japan in 2002, he has held the role of senior instructor at Aikido Kyoto, a prominent Kyoto-based dojo headed by Dojo-Cho, Yoko Okamoto. He holds the rank of 6 dan shihan. In addition to his Aikido expertise, Christopher has been an ESL/EFL teacher and administrator for nearly thirty-five years with an expertise in curriculum development, material selection, and design. In Japan, he has taught full time at several universities (Temple University, Kansai Gaidai, and Ritsumeikan University) as a lecturer, assistant professor, and associate professor.

“Research and development in any field should drive practice, not tradition.”

In both first and second language acquisition, children or beginning students often apply a fallacious learner strategy referred to as “overgeneralization.” This is when learners overgeneralize a grammatical rule in cases where it doesn’t apply. In the case of the past tense, they apply the –ed form with irregular past tense verbs, as well: “I goed to the store,” “I knowed what he said,” “I swimmed in the river.” These are not necessarily errors, but rather interim linguistic stages of their interlanguage (Selinker, 1972). In aikido, we often see the same with beginning students. For example, in the process of doing katatetori ikkyo, where the nage correctly controls uke’s hand while holding the thumb, yet when coming down to pin, nage suddenly changes their grip and holds the wrist as in shomenuchi, or yokomenuchi ikkyo. Here, as in language development, they are overgeneralizing the shomenuchi version of the pin. This is an example of analogies that I often use in my aikido classes. I see the world through the lens of a linguist.

I have been an ESL /EFL instructor for more than 35 years. I have been studying aikido even longer and have been teaching for more than 30 years. Along the way, I have noticed and often incorporated similarities of language acquisition to that of aikido development in the dojo. There are many similarities not only in the metalinguistic acquisition process, but also similarities in the subsequent pedagogical execution of both. These similarities are not just inherent in aikido, but also apply to all body arts in general.

Input

In order to learn language we need input. In language, the input can come in the form of heard speech or written text. The input has to be comprehensible as well. Comprehensible input is input that contains language that is a bit beyond the current understanding of the learner—and the focus is on meaning, not on grammatical form (Krashen, 1982). Children in an elementary school would not acquire Chinese by listening to Chinese news programs, because the input is beyond their comprehension. We move to a higher level when the input is just above our present level, or what Krashen would term i+1 (1982).

In aikido the input comes in two ways basically: visually watching the teacher throw and maybe to a certain extent, the verbal explanations presented. This is visual and auditory input. The input can also come from being thrown. Here, information or input is transmitted by sensation. We get to feel for how the waza should be done, or not be done depending on the quality and experience of the nage. Moreover, the input the learner sees or feels should be within their range of comprehension. Thus, the need for varied levels and the opportunity to train with people who are above their level is essential. Being thrown by the instructor is also crucial because this is the most direct way for a student to be given correct input keyed to the level of the student. The inappropriateness of the input is often demonstrated in seminars, when beginning-level students flounder in intermediate or advanced oriented classes. They see but do not comprehend.

“As instructors, we often see students who have plateaued, or whose development seems to have been arrested or fossilized. The ability to heighten attention and awareness in the dojo is a controversial one. Do we try to lower the affect, making it more relaxing—or does a higher affected, more martial atmosphere help sharpen attentiveness?”

In ESL/EFL, there are those who oppose pair or group work because the input they receive from fellow students at their level will not be near to or native proficiency, providing what is called “bastardized input.” The fear is that input provided by non-native proficiency will lead to fossilization: where incorrect language becomes a habit and cannot be easily corrected. In aikido, the image the students receive is also very important; it cannot be bastardized. If the body is the mode through which this input is transmitted, then the teacher needs to have a command or proficiency when demonstrating. Just like with language acquisition, the input must be provided by a “native speaker.” The critical question then is: Have the teachers who are teaching truly achieved a mastery proficiency of the art necessary to provide the quality input needed for acquisition to occur correctly?

Output

As well as input, we also need output. According to Swain & Lapkin (1995), output allows second language learners to identify gaps or differences in their linguistic knowledge, first by attending to the input and second by making efforts to communicate. We do this by noticing specific features in the input, comparing them to our present understanding, and then attempting to utilize the differences in an utterance. This is what is referred to as hypotheses testing. By uttering something, the learner tests this hypothesis and subsequently receives feedback from an interlocutor. If the utterance is not successful the speaker may (consciously or unconsciously) revise communication—gradually rising to a higher-level proficiency.

In language, interaction usually occurs in discourse, but in aikido it occurs when we throw each other. The learner attends to the input by noticing specific aspects of the teacher’s demonstration, footwork, handwork and comparing it to their present understanding, then with their partner they attempt to apply the difference. The feedback they receive will either validate or negate their hypothesis. This feedback enables reprocessing of the hypothesis if necessary with subsequent throws. Just like hypotheses testing in language, being attentive to the feedback from uke, the student’s proficiency will gradually rise.

An important point to mention here is that the process of “noticing” and “comparing” creates a richer form of input commonly referred to as intake. Many students watch but they do not see! According to Schmidt (1994), a direct link between input noticing and production must be established for acquisition to occur. Only when the input is attended to can further processing be possible and this is especially true when the input is unstructured or lacks a specific focus. The process looks something like below:

Input-noticing–comparing-testing –revising

In Taichi, for example, if I am following my teacher doing the 24 yang form, I notice that her hand position is higher than mine. The comparison helps me adjust getting me closer to a more competent performance. As the teacher comes around and provides correction, she will either confirm or negate the adjustment.

This begs the question of what is the appropriate feedback. How much leeway should students be given in order to expedite their hypotheses testing? Does this directly contradict an art that is often times transmitted in a highly orthodox, stylized manner, thus frustrating the process?

“The input the learner sees or feels should be within their range of comprehension. Thus, the need for varied levels and the opportunity to train with people who are above their level is essential. Being thrown by the instructor is also crucial because this is the most direct way for a student to be given correct input keyed to the level of the student.”

Schmidt (2001) further states that the students’ lack of proper noticing or attention and awareness is the main cause of language fossilization whereby regardless of the amount of correct input a learner is exposed to, many features of the language still become stubbornly arrested in their second language (L2) acquisition.

As instructors, we often see students who have plateaued, or whose development seems to have been arrested or fossilized. The ability to heighten attention and awareness in the dojo is a controversial one. Do we try to lower the affect, making it more relaxing—or does a higher affected, more martial atmosphere help sharpen attentiveness? Moreover, in smaller dojos that do not have the luxury of providing basic classes, beginners who start in mixed-level classes, where there is no systematic pedagogical progression, often miss fundamental features of the techniques that they would have otherwise naturally been exposed to in fundamental classes.

In the dojo, how do we facilitate the input to intake process? In the classroom, the language task or the isolation of specific features in the input creates the opportunity for noticing. A well-structured class with clear goals and objectives helps expedite this process. The teacher creates an environment that makes learning possible and provides a delimited goal to provide clarity. In the dojo, having a theme or specific focus helps students better attend to the input. Clustering elements into a logical provocative flow: Are you just taking five techniques (responses) from one attack or are you using the input to teach a certain principle: for example, where is the point of disengagement from a grab, or using the triangle as a tool for destabilization. The theme gives the input an intellectual or emotional charge that helps the information stick. Additionally, are the classes well-structured, demonstrative, and are the techniques done in a highly repetitive fashion providing repeated opportunities and time for students’ hypotheses testing?

Another way to draw a student’s attention to certain features and encourage noticing is the use of consciousness-raising activities. In grammar, it is an approach that provides specific data and students have to create the rules inductively (Ellis, 2002). Or showing how one feature that seems structurally similar actually operates differently in context. For example, tag questions, which are structurally identical, may have a falling intonation, denoting confirmation and rising intonation indicates the need for clarification. “This is the chemistry lab, isn’t it?” (falling: where the speaker is quite certain that it in fact is) compared to “This is the chemistry lab, isn’t it?”(rising: where the speaker is in doubt and seeking confirmation of the assumption).

On test, students often confuse the handwork on yokomenuchi shihonage and shomenuchi shihonage, the latter requires a crossing of the hands before you strike with a cut. Same is true for yokomenuchi kokyunage and shomenuchi kokunage. Teaching these two forms together, and highlighting the differences implicitly or explicitly may make students more conscious of the differences, creating a higher level of noticing.

Surface Level vs. Deep Structure

According to the Oxford Dictionary of English Grammar (2014): “Deep and surface structure are often used as terms in a simple binary opposition, with the deep structure representing meaning, and the surface structure being the actual sentence we see.” Chomsky (1964) identifies this linguistic dichotomy as a way to address some of the weakness of structural linguistics and to show that language learning is not a process of imitation, but rather an internal cognitive activity. It also helps explain ambiguities in the language. “I shot an elephant in my pajamas,” “Bob likes Mary more than me,” or “Call me a cab, please.” The meaning of the concrete surface representation lies in the deep structural grammatical transformation.

“I recall training with a peer at the Hombu Dojo. Initially, I was trying to be the alpha dog, however, my partner responded with an equal amount of aggression—instead of resulting in mutually-assured destruction, implicitly without verbalization, we adjusted the intensity of our attack, eventually finding a medium for optimal training, where we both benefited. “

In aikido, the taijustu (body art) would be the concrete surface manifestation of a waza, but the rationale for the technique probably comes from the use of sword or spear, residing in the realm of the deep structure. Aihami nikkyo was probably applied when an opponent grabs a swordsman’s hand trying to prevent them from drawing, then the swordsman applying nikkyo with the hilt of the sword as the counter. This may reinforce the belief that only through weapons training do we truly acquire a deeper knowledge of the aikido body arts.

Moreover, because the acquisition of language is an internalized cognitive process, once the process has been triggered, it becomes generative in nature. Chomsky stated that there are unlimited possibilities once the acquisition process has started. Language is not something that is memorized. Aikido in a sense can be the same. Once you have acquired the foundation there is any number of generative possibilities.

Negotiation of Meaning

A basic principle of second language learning is the need to negotiate meaning in any language-learning situation. Once meaning is established, comprehension follows. It is “the process by which two or more interlocutors identify and then attempt to resolve a communication breakdown” (Ellis, 2003, p. 346). It is a communicative repair-oriented “modification and restructuring of interaction between interlocutors when they experience comprehension difficulties” (Pica, 1994, p. 494). Long (1996) suggests that this process creates a higher potential for understanding between interlocutors. The strategies of negotiation, in this case, include the listener’s request for message clarification and confirmation; the speaker may then repeat, elaborate, or simplify the original message. These strategies are also inherent in both L1 (native language acquisition) and in L2 (second language acquisition).

In aikido, we either consciously/unconsciously—verbally or nonverbally– try to achieve a resolution to a breakdown in training—trying to adjust our effort to achieve a medium where optimal training can occur without a win/lose end-game. The negotiation will differ according to the power relationship between each practitioner. I recall training with a peer at the Hombu Dojo. Initially, I was trying to be the alpha dog, however, my partner responded with an equal amount of aggression—instead of resulting in mutually-assured destruction, implicitly without verbalization, we adjusted the intensity of our attack, eventually finding a medium for optimal training, where we both benefited. This negotiation of meaning is also an important part of conflict resolution, the process by which two or more parties reach a peaceful resolution to a dispute.

Accuracy vs. Fluency

In language learning pedagogy, there is a spectrum ranging from accuracy on one end and fluency on the other. Accuracy is the ability to produce language with grammatical and lexical accuracy, while fluency requires learners to produce language in a more coherent holistic way—in normal communication. Where we are on the spectrum, will often be determined by the level or the focus of the class: skill-based vs. communication-based. In more elementary levels, the focus would shift more towards an accuracy-based position, focused on the technical details, and gradually moving to the other end of the spectrum as the level goes up where the details are incorporated into the organic flow.

In aikido, on the accuracy end, working on conditioning skills and basic forms (kihon waza), or gradually grading activities from simple to more complex helps promote this process. The over-reliance on accuracy, however, can create students who lack fluidity and tend to be lumbering in their movement. The need for fluency, getting students to move in a smooth and fluid way, (nagare waza) where they are able to improvise and generate various possibilities is also crucial. Here jyuwaza (free movement) practice can be effective. Where you are on the spectrum, often depends on the level of the students. In basic classes, teachers should lean more towards the accuracy end, and in advanced classes, more towards the fluency side, ending each class with at least 10 minutes of jyuwaza.

Another way the accuracy/fluency dichotomy can be manipulated is by deconstructing a waza (accuracy): breaking it down into its logical parts and then reconstructing it, the same way you would a paragraph or an essay. The deconstructive approach allows students to see the discrete parts and how they connect to make a whole (the trees vs. the forest approach). This is a manageable way to lead students from discrete forms to a whole movement, while at the same time addressing differences in learning styles and broadening the level that can be accommodated in each class.

Peer Learning and Zone of Proximal Development

The zone of proximal development (ZPD) has been defined as: “the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem-solving under adult guidance, or in collaboration with more capable peers” (Vygotsky, 1978, p. 86). Peer learning is a way that you can accommodate a wider range of levels in one class by combining less-experienced students with students who have greater experience or expertise. In the classroom, it is done by skillfully pairing or grouping students with “more knowledgeable others” (Wood, et al., 1976), ensuring classroom interaction, and providing necessary scaffolding and support activities to make the information more accessible to a wider range of learners.

In its pure and productive form, this should be the goal of the sempai/kohai relationship, and not as a form of control and power. I am amazed at how the range of learning possibilities changes in a beginner’s class with the presence of senior students. The less-experienced students are able to accomplish something they normally could not have achieved on their own or with a student of the same level. At the same time, the sempai (more experienced peers) gain a deeper understanding of the skill by transmitting it. We learn the most when we teach something! Therefore, having black belts and more experienced students attend beginner classes not only expands the zone of development but also accelerates the learning process for a whole range of students.

Conclusion

Research and development in any field should drive practice, not tradition. This is illustrated by the poor quality of English language instruction in Japan. Teachers are not informed about the recent developments in second language acquisition (SLA) or are overwhelmed by the stubborn ingrained reliance on an arcane grammar-translation approach where the majority of classroom input is still in Japanese. The more informed you are about the process of language learning, the more effective you will be as a teacher. This also applies to the teaching of aikido. How many instructors are educators, who, aware of the process of learning, are utilizing the latest research and development to create a more systematic, pedagogical approach to the teaching of body arts? Could this be one of the factors for the decline of the art in the USA? Teacher certificates are issued, but based on what? Is there explicit instruction given on how to teach more effectively, how to manage a class (especially of children), and how to manage a dojo? Is attending several seminars a year providing the instruction necessary to be an effective teacher? This-is-the–way-my-teacher-taught paradigm is impervious to the fact that curriculum development and pedagogy is an “ongoing, and iterative process” (Dawley & Havelka, 2004) that is constantly changing according to innovations in the field of education.

References

Chalker, S., & Weiner, E. (2nd Ed.). (2014). Oxford Dictionary of English Grammar. Oxford University Press.

Chomsky, N. (1964). Current Issues in Linguistic Theory. The Hague: Mouton.

Dawley, D., & Havelka, D. (2004) A curriculum development process model. J. Coll. Teach. Learn. 1, 51– 55.

Ellis, R. (2002). Grammar Teaching-Practice or Consciousness-Raising? In J.C. Richard & W.A.Renandya (Eds.), Methodology in Language teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ellis, R. (2003). Task-based language learning and teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gagliardi, A. (2012). Input and intake in language acquisition. (Doctoral Dissertation). University of Maryland, USA.

Krashen, S. D. (1982). Principles and practice in second language acquisition. Oxford: Pergamon.

Long, M. (1996). The role of the linguistic environment in second language acquisition. In W. C. Ritchie & T. K. Bhatia (Eds.), Handbook of second language acquisition. New York: Academic Press, 413–468.

Pica, T. (1994). Research on negotiation: What does it reveal about second-language learning conditions, processes, and outcomes? Language Learning, 44.3, 493–527.

Selinker, L. (1972), Interlanguage. International Review of Applied Linguistics, 10, 209–231.

Schmidt, R. (1994). Deconstructing consciousness in search of useful definitions for applied linguistics. AILA Review, 11, 11-26.

Schmidt, R. (2001). “Attention.” In P. Robinson (Ed.), Cognition and second language instruction (pp. 3-32). Cambridge University Press.

Swain, M., & Lapkin, S. (1995). Problems in output and the cognitive processes they generate: A step towards second language learning. Applied Linguistics 16: 371-391, p. 371.

Swain, M. (2005) “The output hypothesis: theory and research”. In E. Heinkel (Ed.), Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning, 471–483. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wood, D., Bruner, J. S., & Ross, G. (1976). The role of tutoring in problem solving. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 17(2), 89-100.