Easter Sunday. The hope of rebirth. The ancient myths remind me that we are all deeply connected.

The Golden Bough (1890) by Sir James Frazer sits on my bookshelf beside Robert Graves and my high school yearbook. Mildred Beecher, my English teacher introduced me to Frazer’s work because I had asked the difference between a daimon and a demon. She was an extraordinary woman. She read Beowulf in the original and learned patience because she had been strapped to a board, immobilized for months, after breaking her back in a motorcycle accident in England.

Frazer’s full work is encyclopedic in scope, covering twelve volumes. I have only read the abridged version.

The book opens with a description of the rite practiced in a grove of Diana near Nemi, well into historical times. There grew a certain tree, guarded night and day by a man who was both priest and murderer. The Rex Nemorensis, the King of the Wood, held his office only by having killed his predecessor. Each king, in turn, would be slain whenever a stronger or craftier rival arrived. But his assailant had to be a runaway slave who first tore a branch from the sacred tree, the Golden Bough sought by Aeneas as the price of admission to the underworld: the hero’s journey.

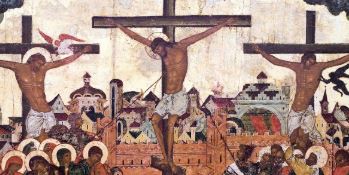

Sir James Frazer finds cognates through time and across the globe. By cataloging, reviewing and comparing the myths, he illuminates the secret of the sacred grove. The slave who stalks about the tree is human mortality whose very life and fecundity, the fertility of his flocks, and the fruitfulness of grain, fruit-trees, and vines, depends upon. He is the god that must die that his vigor be renewed. The ritual killing of a king to fructify the land: King Arthur, John Barleycorn, Adonis, Osiris, Balder, Tammuz. Sacrifice is necessary to ensure that the cycle of life, death, and rebirth continues.

The durability and continuity of the ritual form a pattern identified by Gilbert Murray who also tied it to the solar cycle:

Agon: a contest of the year-daemon against his enemy, light against darkness, or summer against winter

Pathos: a ritual or sacrificial death of year-daemon, followed by an announcement of the same by a messenger

Threnos: a lamentation of the death of the year-daemon

Theophany or Peripeteia: a resurrection and epiphany of the year-daemon, which is accompanied by a change from grief to joy

The rare Easter services I attended concluded with the joyous Paschal greeting, “Christ has Risen!” A wonderful sentiment to remember.

Frazer’s work encourages a review of Christ’s lineage beyond the pattern of his death and resurrection. Jesus was born in Bethlehem, the House of Bread, which was also a seat of Adonis worship. His virgin birth, the sudden shining star, the gift of myrrh, even the straw on which he was laid, are a continuation of more remote and divine precedents. It is a recognition of patterns greater than man, coeval with the conception of time. The gods cannot come to birth until there is knowledge of the revolving year and memory of the seasons’ return. It is to these gods that myth rightly assign the gifts of civilization; wheat/corn and beer/wine.

As civilization advances we collectively forget the deep chthonic connection to the earthly cycle. But the ritual is before us with the sacrament: To eat the body of the God, to drink His blood (relic of a savage rite), is still to celebrate life. The palliative against the raw fear that life might cease.

Growing up in Protestant Connecticut, ceremony and ritual were secondary to scripture. Although I respect his intellectual and individualistic spirit, I have come to conclude that Luther was wrong. By giving primacy to the text over ritual, the Protestants rejected the essential mystery. In discarding the Mass, they were depriving god his powers to fructify and rejuvenate; breaking the visceral connection to the ancient cycle. Ritual is the vestigial substructure of modern civilization.

Especially now, with a potential disruption in the food chain created by Covid-quarantined migrant labor not picking crops, the importance of ritual is reasserted: to remind us all of our connection to the earth and our dependency on it for sustenance. It is a call to mindfulness.