Yesterday (October 3, 2025), Heidi and I visited the Hoover–Minthorn House in Newberg, Oregon. The house, built in 1881 by Jesse Edwards, the Quaker founder of Newberg, stands behind a white picket fence, its clapboard walls repainted in pale yellow.

Murray Rothbard had already set my prejudice against Hoover, so the visit was a sardonic excuse to do something ironic. The museum is sparse and quaint, so obviously devoid of artifacts that I was amused when the docent asked “Is this your first time visiting?” – why would anyone come a second time? Nevertheless, it was an educational visit. I hadn’t realized Herbert Hoover was an orphan, raised as a Quaker, or knew anything about his uncle, Dr. Henry Minthorn.

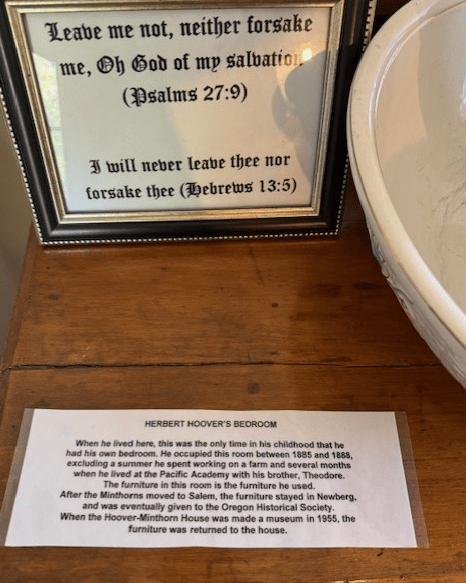

I mused that the house, originally built for the founder of Newberg, was small and modest even by New England Protestant standards. The sparse furniture is advertised as having been used by Hoover as a boy: a small bed framed in walnut, a washstand with a ceramic pitcher, a plain dresser with turned knobs and no veneer.

This is furniture meant to teach sufficiency, not luxury.

But how did Hoover come to live with his uncle? Hoover arrived in Oregon in 1885, at eleven years old, sent west to live with his maternal uncle Dr. Henry John Minthorn after the deaths of both parents. The Minthorns, Quaker educators recently settled in Newberg, offered him structure. Hoover would later recall, “The doctor was a mostly silent, taciturn man, but still a natural teacher.” The boy became, in effect, a junior apprentice, helping with his uncle’s patients, working in the family garden, and attending Friends Pacific Academy (today’s George Fox University). Years afterward, Hoover referred to Minthorn as “my second father,” and though the remark is affectionate, it carries the tone of duty rather than warmth. Hoover summed his uncle/father:

He had originally been sent to Oregon as a United States Indian agent. He was one of the many Quakers who do not hold to extreme pacifism. One of his expressions was, “Turn your other cheek once, but if he smites it, then punch

Herbert Hoover, Memoirs of Herbert Hoover: Years of Adventure, 1874–1920

him.” With this background of sporadic talks from him, the long tedious drives over rough and often muddy forest roads became part of my education.

Dr. Minthorn was superintendent of the Chemawa Indian Training School, one of the government’s assimilation institutions founded on the belief that Indigenous cultures must be “civilized” through labor and erasure. Under Minthorn’s tenure, children were compelled into unpaid work, punished for speaking native languages, and drilled in what the Bureau of Indian Affairs then called “habits of industry.” The system was unquestionably brutal; an experiment in moral improvement through coercion. The lesson for young Hoover was paradoxical: that compassion could justify discipline, and that order could masquerade as care. The logic of benevolent control, first rehearsed in his uncle’s school, would echo later in his own administrative life, where relief and regulation became indistinguishable gestures of conscience.

In his mid-teens, he left Newberg for California to attend Stanford University, newly opened and dedicated to the fusion of moral purpose and applied science. He studied geology, worked his way through school, graduated in 1895, and entered the world as a practical idealist.

He began modestly, as a mining engineer, moving quickly from the American West to Australia and then to China, Burma, and London. He developed a reputation as the man who could “make a sick mine well.” By his mid-30s he was internationally known and, by the standards of the day, independently wealthy, worth several million dollars by 1914. Wealth gave him freedom from clients, employers, and ordinary constraints. It also hardened a conviction: that competence was legitimacy.

Engineering is a noble profession. The great liability of the engineer compared to men of other professions is that his works are out in the open where all can see them. His acts, step by step, are in hard substance. He cannot bury his mistakes in the grave like the doctors. He cannot argue them into thin air or blame the judge, like the lawyers. He cannot, like the architects, cover his failures with trees and vines. He cannot, like the politicians, screen his shortcomings by blaming his opponents and hope the people will forget.

Herbert Hoover, “Engineering as a Profession,” address at Columbia University, February 17, 1908.

Hoover’s success abroad coincided with the twilight of the high-Victorian faith in progress. Where earlier generations spoke of Providence, Hoover spoke of planning. For him, engineering was moral architecture. The moral engineer was not a philosopher but a solver of problems.

The engineer is the pioneer of progress, the builder of our civilization. He must be honest not only in his works but in his purpose, for upon him rests the material foundations of our national life.

Herbert Hoover, Address to the American Society of Civil Engineers, 1910.

It’s no surprise that when the First World War broke out, his instinct was not to choose sides but to organize relief.

In August 1914, with Europe paralyzed by mobilization, more than one hundred thousand Americans found themselves stranded on a continent suddenly at war. Banks had suspended credit, telegraphs were cut, and steamship routes were seized for military use. London was crowded with anxious travelers who could neither pay their hotel bills nor return home. Hoover, then a prosperous mining engineer living in Mayfair, was the obvious man to turn to: solvent, respected, and organizationally fearless. Within twenty-four hours of being approached, he convened a committee of volunteer businessmen, opened offices throughout the city, and personally advanced funds to those in need. “Within twenty-four hours,” he later recalled, “we had organized a committee, established a hundred offices, and had found food and shelter for more than ten thousand Americans.” His committee soon arranged for special trains to carry destitute tourists to ports, and by the end of the crisis had repatriated more than 120,000 people.

That extraordinary efficiency brought him to the attention of diplomats. The American ambassador in London, Walter Hines Page, and U.S. Minister to Belgium Brand Whitlock asked Hoover to coordinate a far more daunting mission: the feeding of an entire nation. Belgium, occupied by German forces and cut off by a British naval blockade, faced starvation. Hoover accepted at once, founding the Commission for Relief in Belgium (CRB) in November 1914. It was a private, neutral organization, an early NGO with quasi-sovereign scope. The CRB negotiated directly with the British and German governments, arranged shipping under a special flag, and distributed food to nine million civilians under strict supervision.

I had never been in public life, yet suddenly I found myself dealing with governments, generals, diplomats, and kings.

Herbert Hoover, Memoirs of Herbert Hoover: Years of Adventure, 1874–1920

Over the next four years, the CRB delivered more than five million tons of food, financed largely by private credit Hoover secured from American and British banks. He operated outside formal government channels but with the confidence of them all. His success transformed him from engineer to humanitarian and, in the eyes of millions, from private man to public servant.

The pattern that would define the rest of his life was set: moral obligation expressed through management, compassion rendered as logistics. Hoover’s genius lay in administration: he persuaded warring governments, organized supply chains, and kept volunteers working under impossible conditions. Hoover harnessed the power of non-coerced but coordinated human activity.

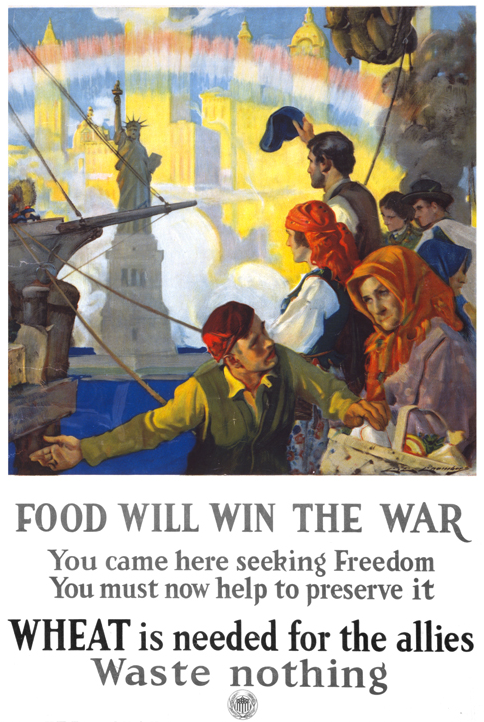

When Congress passed the Lever Act and Wilson created the U.S. Food Administration, he tapped Hoover, who agreed only on condition of a free hand and a direct line to the White House. Hoover then declined any salary, arguing he could better ask Americans to sacrifice if he took none himself. Though the statute armed the agency with licensing and other controls, Hoover ran the program by persuasion: a nationwide, voluntary conservation drive with encouraging slogans, “Food Will Win the War,” meatless and wheatless days, pledge cards, and home-economy pamphlets, designed “to appeal to volunteerism and avoid coercion.”

By 1920, Hoover had become an international figure; admired, rich, and politically unaligned. Both parties courted him. He declined. Politics, he claimed, was a distraction from constructive work. But the distinction would not hold. Moral engineers inevitably drift toward power, because power is simply authority in its most efficient form.

The ideal of efficiency is a moral one… Waste is immoral because it results in loss of life, of comfort, of happiness.

Paraphrased from Hoover’s essays and public speeches collected in American Individualism (1922).

In 1921, President Harding offered Hoover the post of Secretary of Commerce. It was a minor department; Hoover made it central. He modernized industrial standards, promoted aviation, radio regulation, flood control, and statistical coordination. He believed government should guide, not command, “a partnership of service,” as he called it. But partnerships require hierarchy. Over time, his “cooperation” looked increasingly like supervision.

When Coolidge declined to run in 1928, Hoover was the obvious successor. He campaigned as a business-progressive reformer and won in a landslide.

Then came the crash.

Historians generally portray Hoover as the president who “did nothing” while the economy collapsed, the passive apostle of laissez-faire. But this fails to appreciate what Hoover knew from direct experience worked, voluntary coordinated action. He had proven success with the CBR and the Food Administration. Hoover never conceived of deficit spending as a legitimate policy; he endured it as a failure of circumstance. “The course of unbalanced budgets,” he warned, “is the road to ruin.” His deficits arose not from Keynesian conviction but arithmetic necessity: collapsing revenues, emergency relief, and congressional pressure to “do something.” Like the Smoot–Hawley Tariff, it was an act of political concession rather than conviction. By 1932, he presided over a $2.7 billion deficit (the largest peacetime shortfall in U.S. history) while simultaneously raising taxes to restore balance. The irony, as Rothbard later observed, is that Hoover became “the first Keynesian president by accident,” creating the prototype of New Deal interventionism while still preaching fiscal rectitude.

Between 1929 and 1933, Hoover expanded federal spending from $3.1 billion to $4.6 billion, a 47-percent increase in the midst of economic collapse. The national budget swung from a $700 million surplus to a $2.7 billion deficit, the largest peacetime fiscal shift in U.S. history to that point. Hoover’s administration launched vast public-works programs, loans through the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, and emergency credits to banks and railroads, measures that broke with classical orthodoxy, even if they are considered de rigueur today.

For Rothbard, interventionism exacerbated the problems, so his calling Hoover a natal New Dealer is an indictment. a man whose moral compulsion to coordinate and correct led him to prefigure the very administrative state that would replace him. Rothbard labels Hoover the first interventionist Republican, the prototype of Roosevelt. “The myth of the ‘do-nothing president,’” Rothbard wrote, “is one of the most grotesque distortions of our historical record.” Hoover’s every instinct to stabilize, coordinate, and act delayed recovery. To Rothbard, the Depression was not cured by the state but prolonged by it.

Rothbard’s critique is brutal but clarifying. To his credit, Hoover’s interventionism did not spring from a lust for power but rather from virtue: the same virtue that once organized Belgian relief. He simply transferred the habits of humanitarian control to the domestic economy. Where a believer in liberty sees crisis as a teacher, the moral engineer sees it as a design flaw. His reflex is correction.

Rothbard’s larger argument (in America’s Great Depression and essays such as “Herbert Hoover and the Myth of Laissez-Faire”) rests on a psychological as much as an economic diagnosis. The Quaker ethic of moral stewardship, Rothbard suggested, translated into political paternalism.

Hoover was the prototypical ‘progressive’ who sought to substitute the discipline of the market for the moral guidance of the State, administered by a hierarchy of experts.

Murray N. Rothbard, Herbert Hoover and the Myth of Laissez-Faire, The Freeman (1959)

Hoover’s conviction that goodness and expertise were twins made intervention appear righteous.

After his defeat in 1932, Hoover endured years of vilification, blamed for breadlines he had tried to prevent. (The contemporaneous label ‘Hooverville’ for Depression-era shantytowns was itself a popular indictment of his policy failures.) Yet he outlived his critics. By the 1940s and ’50s, his reputation had softened; President Truman enlisted him to head the Hoover Commission on Government Reorganization, a grand attempt to make bureaucracy more efficient: a final, ironic testament to his lifelong faith in organization.

He spent his last decades writing, lecturing, and defending the ideals of private initiative and voluntary cooperation. But the record speaks otherwise. The man who preached voluntarism had once cajoled industries into conformity; the champion of efficiency had presided over systemic collapse. His contradictions were American ones; moralism expressed as administration, benevolence fused with bureaucracy.

Buckminster Fuller, born twenty years after Hoover, inherited the same civilizational optimism but redirected it toward design rather than governance. Hoover wanted to feed the hungry; Fuller wanted to eliminate hunger through material abundance. Hoover trusted the morality of cooperation; Fuller trusted the inevitability of technology. Hoover’s mind was procedural, Fuller’s visionary. Yet both shared a premise: that humanity could be engineered into virtue.

Had Fuller ever governed, the result might have been beautiful and disastrous: geodesic bureaucracies, aluminum utopias, public housing as sacred geometry. Rothbard would have recognized in Fuller the purest expression of the same hubris: design as destiny. Both men believed that good will plus technical intelligence could outwit disorder.

Standing in Hoover’s childhood bedroom, you sense how early the pattern began. The furniture’s plainness carries a moral aftertaste. The washstand bears a small plaque quoting Psalms and Hebrews: “I will never leave thee nor forsake thee.” The verse, meant as comfort, reads here almost as a command. The Quaker household permitted no extravagance, no idleness, no self-indulgence.

His uncle’s life offers the footnote. Dr. Minthorn genuinely cared for his Indian school wards, but he also believed they could be “civilized” by erasing their cultures. He embodied the archetype of benevolent coercion: moral improvement imposed as duty. The continuity to Hoover’s later governance is chillingly direct. The doctor’s clinic becomes the president’s economy, both structured around the assumption that human suffering is an engineering problem.

I’m not as absolutist as Rothbard, but the moral geometry still troubles me. Markets and human liberty remain untidy, inefficient, and occasionally cruel. But they are also the only feedback system that coordinates without moralizing. Every moral engineer begins with the best of intentions: Hoover feeding Belgium, Fuller designing a world that works for all, Dr. Minthorn educating the “wards of civilization.” Yet, once institutionalized, each ends by constructing a system that sustains itself rather than solves the problem it was meant to address. The institutions become centralized, self-justifying, not problem solving.

The engineer’s burden is the conviction that human failure can be prevented by better plans. The harder truth is that failure is the one mechanism that keeps us free. Markets correct because they allow error to occur. Liberty endures because it tolerates imperfection.

Hoover never learned that lesson; Fuller never had to. Both believed virtue could be systematized, and both mistook coordination for consent. Rothbard, the unrepentant skeptic, saw the danger early: that even good men, armed with moral purpose and organizational genius, can produce tyranny by efficiency.

_____________________

In 2025, tariffs rise again under the banner of national strength, as though protectionism were patriotism reborn. The old Hooverite delusion, “we can design stability,” is revived by men who have never known restraint. The new tariffs, imposed with swagger and incuriosity about consequence, deliver the same ruin: collapsing supply chains, rising prices, vanishing trust. Where Hoover acted from conscience, Trump acts from appetite (and without Congressional authority). It is not stewardship that guides him, but vengeance masquerading as strategy.

Hoover at least believed in order as a moral duty. Trump believes only in domination as a personal right. Where Hoover agonized over deficits and balance, Trump boasts of leverage and threat. Hoover’s tariffs were a blunder born of misplaced faith; Trump’s are a weapon aimed at spectacle. What Hoover did out of misguided virtue, Trump repeats out of performative bullying.

Hovering over this new administration are its engineers. This time not Quakers but profiteers like Elon Musk, self-anointed visionaries of efficiency who see government as a machine to be optimized (data mined?), not a republic to be tended. Hoover sought to redeem waste through planning; Musk and his peers sanctify chaos as innovation. Their “efficiency” has no moral core, no Quaker plainness, no limit. They want to run government as a platform devoid of conscience. It is Hooverism without virtue, Fullerism without beauty, management without mercy.

We have come full circle: the same administrative will to control, now serving ego instead of order; the same rhetoric of efficiency, now severed from any ethic of care. The arrogance of government “providing solutions” has reached its terminal form: a state not of benevolent control but of predatory calculation. Every Hoover needs a Rothbard to remind him that efficiency without liberty is tyranny. In 2025, no such reminder is heeded. The result is not the tragedy of good men mistaking virtue for power, but the spectacle of powerful men mistaking power as a virtue.

_____________________

Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum – published writings