Mulligan Sensei is currently 6th Dan and, with his wife Okamoto sensei, runs Aikido Kyoto. Okamoto and Mulligan sensei started the Kyoto dojo upon their return to Japan in 2003. Before Kyoto, Mulligan and Okamoto sensei founded Portland Aikikai. But the journey started well before then.

_______________________________

Mulligan Sensei, thank you for taking the time to give us insights on your training and development as a martial artist. As I recall you had a challenging youth.

Well, I was born and raised in Syracuse, NY in a blue-collar, mostly Italian, German neighborhood. There were three girls and three boys plus myself, making that seven; I am fifth born. In my infancy, both my mom and dad drank heavily to the point of becoming alcoholics. My dad was extremely erratic and violent. He eventually went to prison for 10 years for various offences. My mom was stuck raising seven kids on her own.

That must have been difficult for her to say the least.

She tried her best but was mostly ineffectual along the way. She eventually quit drinking, so Alcoholics Anonymous was an integral part of my life growing up: AA Christmas parties, Easter egg hunts, and summer picnics, meetings in the home, and her counselling people late at night on the verge of relapsing.

I can only imagine that was impactful on you as a youth.

My environment was extremely chaotic and violent not only at home but outside. I had a terrible temper, and usually, resolved issues in a violent manner. I remember fighting on the way to school at school and on the way home. I was small but scrappy, and usually wouldn’t back down. That often resulted in me getting a good ass whipping from time to time. I think besides the chaos at home being both ADD and dyslexic compounded my daily frustration. I failed first grade and was in special education classes until 5th grade. I also had to attend anger management class twice a week with a counselor at school. I remember always being the dumbest kid in class who could never read out loud or spell. That along with being on welfare and having a father in prison didn’t do wonders for my self-esteem. Shame was an emotion I knew well, but how you use this emotion makes a world of difference: Does it crush you or do you use it as a motivator?

Were martial arts an outlet then?

No. I never excelled in sports, and would usually quit after a few weeks of tryouts. I did play a lot of street spots. I did, however, learn to swim at summer camp, eventually achieving junior life saver. In junior high, I stayed on the gymnastics team for a year. In high school, I did nothing. By the age of 13, I was smoking, drinking and already doing soft drugs, By 18, I was a physical wreck, and landed in the hospital for three weeks with severe pneumonia.

How did you pull yourself out of that? It seems like you were on a downward trajectory.

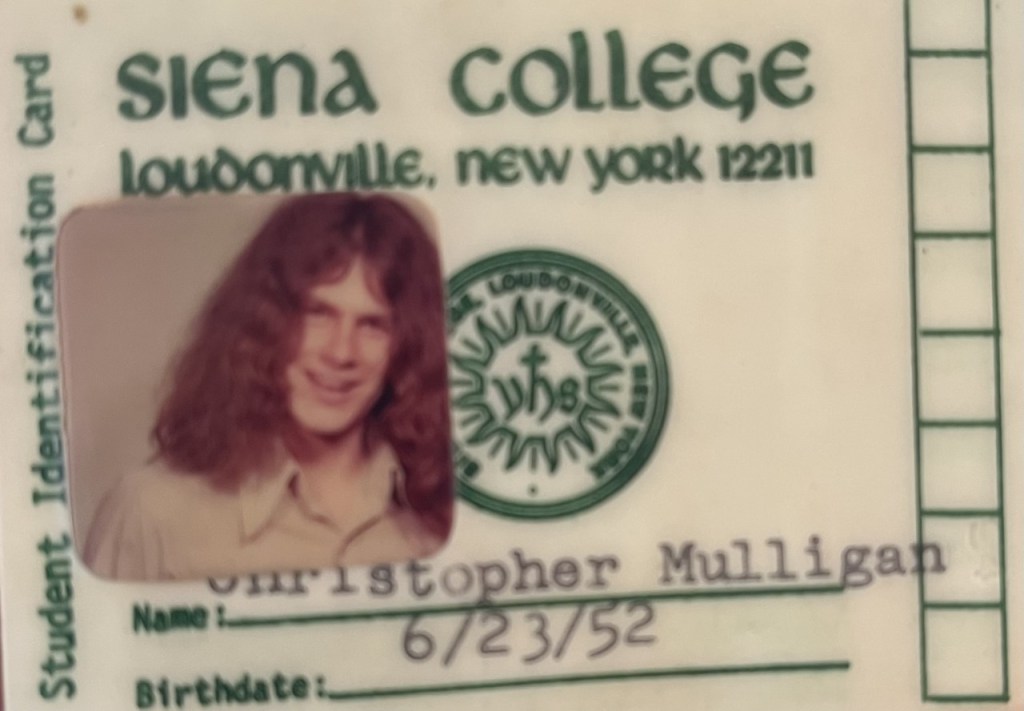

Miraculously, I was able to score a scholarship as a financially disadvantaged student in the first wave of Affirmative Action kids in 1970. I was the token poor white-boy in my group, entering a Catholic University, Siena College.

Growing up Catholic, I had attended Catholic school for seven years; we were all charity cases, so the Catholic doctrine, education was not alien to me. In college, I started yoga, became a vegetarian and started running every day. And music is of course an important part of the social environment.

I have mentioned you know your classic rock!

I have always loved the history of Rock and Roll. I tend to have a photographic memory when it comes to facts like that. Maybe that is why I majored in history.

Sorry – back on task. Clearly you have a high degree of motivation – the quest for self-improvement. Did this quest lead you to martial arts?

I was running every day and on one run, the cross country team ran by, so I joined them on their run. Afterwards, the coach asked me to join the team. From around this time I began searching, trying to improve myself. Along the way, I became interested in a system called Eckankar, which I belonged to for 10 years. In my freshman year, I started looking for a martial art to do. The karate and Kung fu places were too expensive and very commercial. An Eckankar friend turned me on to Aikido.

Clearly your formative years were during some of the greatest changes in the social experiment – not only the Affirmative Action and social justice changes, but also the new spirit of consciousness that was making a deep impact. Eckankar to Aikido – how old were you then?

I was around 20 when I started.

Who was your first teacher?

My first teacher was Ariff Mehter.

What was his background? Aikido hadn’t yet gained traction as a common martial art yet: you began training in 1972.

Mehter sensei had started Aikido in Burma and was working as an engineer or student in Syracuse. He had joined Yamada and Kanai sensei’s group when he opened his dojo. His Aikido was very precise and fast. He was smaller, so relied on his quickness to execute the technique.

What was the dojo like?

I remember the mat being sawdust with a canvas tarp over it; mountains and valleys. It had absolutely no consistency. I trained almost every class at first and would venture down to New York Aikikai from time to time

Where did you go from there?

I moved to California in 1976. When I moved to the Bay Area, I just wanted to get out of Syracuse. I had a sister living in San Jose. When I got there, I visited several dojos, but Frank Doran sensei was the most normal, straight up. I mean you could train in his class, and he didn’t do all the new age fluffy stuff. The Bay Area is interesting. You had the harder Iwana style, with Bruce Klickstien [1] and Bill Witt, and then you had the New Age stuff with lots of taking. At that time Frank was pretty grounded. It’s when he started following Saotome sensei, Ikeda sensei that he changed.

How long were you with Doran sensei?

I trained with Frank Duran sensei for two years in the Stanford Aikido club.

As a former Marine I can imagine Doran sensei would have a very practical core.

Frank was technically proficient, having actually been to Japan for a year training with Tohei sensei at Hombu. He had come into Aikido from judo, but had many influences, Saito sensei, Saotome sensei, and Hikitsuchi sensei. Frank seemed to change his allegiance regularly but had an uncanny ability to always maintain his core style.

What rank were you then?

I trained with Frank Doran for two years, finally reaching 1st kyu.

How did you get from California to Japan?

While I was training with Doran sensei, Hikitsuchi sensei from Shingu taught a seminar. I took some of his ukemi, and he invited me to his dojo. So for the next six months, I saved my pennies and went to Shingu.

Did you visit Hombu?

I stopped at Hombu on the way. I got my ass kicked by Miyamoto sensei in [the first] Doshu’s class [Kisshomaru Ueshiba 1921-1999]. The same day, I went to Chiba sensei’s class and got my ass kick some more by the uchi deshi. As an American 1st kyu, I could do nothing with these guys, yet they had their way with me. It was truly an eye opener.

There is amazing consistency – Miyamoto sensei still trained in Doshu’s class when I was there many years later. But you didn’t stay at Hombu and continued to Shingu. What was the training like there?

The Shingu style is very different. You are supposed to execute the technique without having any openings, sometimes to the point of absurdity. They apply atemi often, thinking that it helps eliminate any opening that may occur. I think, often times, in the motion or on the offensive the opening is naturally eliminated. Hikitsuchi was very much into the Omoto-kyo Shinto that influences O Sensei. He would chant koto dama every morning. I trained every class, sometimes three times a day. Lots of swari waza. Their weapons work was very different and instead of jo, we did bo kata. We never did any kumi jo or ken. Personally, I found Hikitsuchi to be a sham and was never impressed with his Aikido, although he liked to call himself a 10th dan, which was controversial.[2] If you look at videos of shingu teachers, you can draw your own conclusions.

Looking back – since the Shingu style wasn’t your ultimate path why did you go there?

Remember, my visa was sponsored by Hikitsushi sensei, so I was obligated to go there, even though the training at Hombu was much better.

What were the key elements of training that you were looking for at that time?

When I arrive in Japan, I was still in my 20s, had been a marathon runner, and so was full of stamina. The training in Shingu was vigorous but lacked the resistance that you may get at Hombu or even Iwama. The only real quality training was when shihan or senior students showed up and that was occasional. Otherwise, you were stuck with one of the many hapless foreigners.

How did you come to leave Shingu?

While at Shingu, I started teaching a young lady English, we eventually became romantically involved, and unbeknownst to me, she had Yakuza affiliation. Her mother was a money lender. This created a major rift with Hikitsuchi sensei, and I was asked to leave, which also compromised my relationship with Doran sensei. We fled to Osaka, but now I was without a sponsor or a dojo to train in. I had to look around for a place to train, finally ending up at Tenshin dojo with Seagal sensei.

Steven Seagal was one of the reasons I started Aikido – his first movie gave it real legitimacy. What was he like?

When I knew him his name at the time was Seigel – he was a charming guy and persuaded me to train there. I was basically an uchi deshi, training in all the classes. He was very strong and fast; some of his ukeme is very demanding. He also comes from a karate background. The overall level of training was not that good, especially on a technical level. From time to time, he would have these special classes, where you had to get your partner to tap out in some way. They usually degenerated into a brawl. On the tests, I recall the basics for sankyo, nikkyo to be very poor. I eventually took my 1st black belt with him. His tests are tough: blood and guts. You can see some of them online. He is not so concerned about technique but rather your ability to defend yourself, hold your ground. If I learned anything from him and training at his dojo, it was this.

I recall a few stories you have told about Seagal sensei, but perhaps we save those for another time. After the Tenshin dojo you went to Hombu – how did that transition go?

When I finally went up to Hombu, I may not have been as technically proficient as others but I could hold my own. In one of my first classes, I trained with an American guy. He was big, strong and looked like an ex-marine. He loved to challenge new people coming into the dojo. I gave him no ground and it degenerated into a real brawl.

So much for Aikido being peace love and understanding.

Well after that encounter I became really good friends with him. As it happened Shibata sensei was teaching the class, and I think he was impressed. After he asked me where I was from, giving me a kind of nod of approval.

Hombu Dojo then is where you began to refine your Aikido technically?

Seagal has a very specific style, suited more for a taller person. At Hombu, I basically had to unlearn and redefine my Aikido. Hombu is a great place to train as you know, but not the greatest place to learn. The ukeme at Hombu is also much better – but mostly learned implicitly by being thrown.

At Hombu, there are so many good people to train with, but you have to be selective, considering you don’t change partners throughout the class. You may end up with someone totally useless. I would usually sit next to or chat up someone, mostly the foreigners, and then end up training together. I was not very popular among the French, who usually avoided me.

All the Shihan are so different especially at that time. I understand now why the French, for example, choose teachers that are alike, Yamaguchi, Yasano, and Endo sensei in order to gain a certain consistency. I floundered there for a year or so, until Didier Boyet started giving me some guidance, and starting a private class with Shibata Sensei.

So the technical refinement was primarily due to private lessons with Shibata Sensei. How did that work?

I think in early 80’s, then we agreed to form a private class with Shibata sensei. The cost, at that time 50,000 yen a month, twice a week. The instructor gets maybe 5,000 of that. We usually were five people, the core being Yoko, Didier and myself, the other two would change according to who was there. This is when I really began to learn. The classes were brutal. Didier and Shibata sensei had already had years of weapons experience. Yoko and I were thrown into the deep end: move your ass or die. That seemed to be the emphasis at first; learn to react, hold your ground, then the refinement came. Obviously in those classes we were training with Shibata and Didier all the time. We would start off with some taijutsu, then weapons which would alternate from jo to ken and sometimes take away techniques. At night, he would turn off the lights and have us do the kumitachi in the dark – real ninja stuff. Shibata sensei had two private classes going on at that time and occasionally he would combine the two which became very competitive.

How was the training level at that time?

The average level at Hombu at that time appears to have been higher than it is today. There were so many people that you usually could find someone good to train with unlike a small dojo like Shingu. While at Hombu, I ventured up to Iwama. Saito sensei’s son-in law would come to the 3:00 classes. We would train together; he invited me up. I did not like the training– there were not a lot of good people on the mat. It may have been a down time, inundated with foreigners. I always found that style to be very lumbering, stylized. They did do a lot of tanren 鍛錬 keigo as opposed to the nagare 流れ form. At Hombu, because of the breadth of teaches and styles, there was more flexibility in your growth. Interestingly, considering the differences, you can still see a solidified Hombu style emerging.

I always found it curious that the direct students of O Sensei were all so different. Osawa, Yamaguchi, Saito, Nishio, Arikawa, Tada and Shirata senseis all were very distinctive, yet the farther one gets from this direct lineage the more similar the style has become. I think O’Sensei or the organic development of an art that had yet to be standardized gave those earlier shihan more freedom to develop their own Aikido.

It does seem that the Hombu Aikikai “style” – despite different teachers and emphasis – coalesced into a relatively cohesive form.

Yes, it was Kisshomaru Doshu who actually categorized and stylized the Aikido forms into a comprehensive syllabus. The older teachers often bristle at the notion of omote/ura. Yamaguchi sensei never made a distinction.

I didn’t realize that – I had made a similar observation

This distinction was something established by Kisshomaru. Thus the morning class being the vehicle to maintain the Hombu Aikikai style even today. The present Doshu doesn’t have the luxury that Yasuno and Miyamoto, or Shibata sensei do in going off in a different sometimes unorthodox direction. He has to be the standard bearer.

You also studied iaido while in Japan and have a deep appreciation for weapon work, but it is not typically taught.

At Hombu, there are no weapon’s classes, not even weapon take away, which ironically are required on the tests. Didier introduced me to Mitsuzuka sensei and I studied iaido formally with him for several years.[3]

You met Yoko while training at Hombu of course – and eventually married and had two boys. You moved back to Portland to raise a family. But you also wanted to train. As I recall you really started teaching of necessity – you were both 4th dan when you arrived, but had to teach to find people to train with. How was the transition from student to teacher?

By the time we came to Portland, I had implicitly internalized the style, but I hadn’t articulated it to the point where I could teach it in a comprehensible fashion. Yoko and I would argue about whether something was aihami or gyakuhami, which handwork was correct. As you remember in the first dojo I taught in, I would often argue about form with the other instructors. Even Yamada and Kanai sensei had different ways of doing things and even called the same technique by different names. By teaching, and trying to standardize both of our approaches, we were able to formulate a Portland Aikikai style. Of course allowing for certain individual interpretations. I think you get to a point in your training when the only way to grow or understand the art better is to teach it. It has to make sense not only to the practitioner but also to the people you are trying to impart the information to

Personally, as a teacher, you either have it or you don’t. Without it, it is possible to be good, but you will never be exceptional. It’s in your blood, kind of a vocation. I think I have that. But with any body art, the body is the mode of expression–if you haven’t mastered the art you can’t express it effectively. Your body has to be able to express the concepts that you are trying to impart!

When did you start teaching English professionally – you have taught at several universities throughout your career and often use language acquisition as a metaphor for learning Aikido.

I started teaching English in Shingu; there are not many ways a foreigner can make money there. In Osaka and Tokyo, I taught in language schools and high schools. When I met Yoko, and she became pregnant, I had to decide on a serious profession, so I entered Temple University Japan’s applied linguistics program. That was a tough time; working full time in a high school, training almost every day and going to school at night with another baby on the way. When I graduated, Temple University hired me into their English language program. I taught there until we moved back to the states where I taught at Pacific’s University’s English Language Program for 12 years. Upon returning to Japan in 2002, I was an assistant and then associate professor at two universities.

I used your generative linguistics idea to justify my own explorations of FMA.

Well as Chomsky stated: grammar/language is generative – there are unlimited possibilities once the acquisition process has started because it is an internalized cognitive process. Language is not something that in memorized. Aikido should be the same. Once you have acquired the foundation anything is possible.

If we follow this metaphor then the challenge is to make sure one learns the ‘deep structure.’ How does that play out on the mat?

Teaching language and body arts is very similar. There has to be comprehensible input at just the right skill level. In Aikido the input is visual, not verbal like language, so the image the students get is very important. The teacher needs to have a command or proficiency when demonstrating, just as the input an English learner hears needs to be almost native. In language, interaction is important; this usually occurs in discourse, but in Aikido it occurs when you throw each other. The teacher throwing the student gives them a feel for how the technique should work. Then by comparing your present approach we make adjustments and go to a higher level. This is what Chomsky would refer to as hypothesis testing. The way I take a difficult technique or idea and make it accessible to lower level students is through scaffolding: breaking it down into its logical parts or demonstrating it like you would an essay, then providing the pre-development skills necessary to execute the technique and then grade the movements from simple to more complex until you have the whole. This is the same way I teach language.

I have always admired your methodology and pedagogical flourish. The visual input has to be precise, but also memorable. There is the art of the ‘show’ as well as the beauty of the efficiency and accuracy of the movements. But as children of the West I think that good instruction has to be like a good movie – compelling visuals, good narrative, and a logical structure and flow. Too often I see teachers who do nothing more than one damn thing after another…

I just had a discussion with Malory Graham sensei (of Seattle Aikikai) and we were discussing some of the reasons that Aikido membership in the States is declining. She believes, and I agree, that it is mainly bad teaching. To be a good teacher, you first have to have mastery of the art and that usually doesn’t happen until around 4th dan. In many cases, you have people teaching at shodan with limited expertise or older people who haven’t gained the proficiency and are physically out of shape. What kind of impression does this create? How can you attack students this way? Moreover, what kind of pedagogical training is provided? How about classroom management skills? People receive their fukushidoin and shidoin certificates but it doesn’t mean they can teach.

We should have a separate conversation regarding teaching and specifically the development of teachers in general. I had made a brief post touching on that topic, but it is well worth exploring more.

So in summary – you started in 1972, trained in Japan from 1978 to 1989 when you returned to America. Then trained and taught until founding Portland Aikikai with Yoko in 1991 where you taught until returning to Japan in 2003. I have the great honor of having trained with you and Yoko since 1991 – before Portland Aikikai was founded. At that time there was a consortium of instructors and a group of us cajoled you both into starting a dojo of your own. I have made brief comments on the founding of Portland Aikikai but it is hard to understand the seminal influence you had on us

Yes, working with other people has always been my weak point. Both Yoko and I are extremely stone-headed. I was ready to start our own place well before when we did, but Yoko’s main concern was the children, our family. She wanted to make sure that if we left that our dojo would be serious – she wanted to do it professionally.

Looking back, now that I am a father of two boys, I am even more amazed by your dedication. Meaning, you were teaching English at Pacific University full-time, raising your boys, and teaching Aikido. Obviously you and Yoko shared those responsibilities, but I remember you were both on the mat together a good percentage of the time.

Is it possible to have a dojo and a family at the same time when your spouse is also working full-time? Fortunately it fit perfectly with our lifestyle. The classes were scheduled so one of us could be home when the kids went to school and when they came back. When they started training at the dojo we could all go together. It became a family affair. And the students of the dojo became their big brothers and sisters. My job also gave me a great deal of flexibility – generous vacation time and no set working hours. Also, having a spouse who also does the same art and is not jealous of the time you spend away from home is crucial.

It surprised me to do the math – you started training in 1972, taught at Portland Aikikai for 12 years and have now been in Kyoto for 14 years. Looking back what are your impressions of how Aikido has changed over the last 45 years since you began training?

How has Aikido changed over the years? I don’t think Aikido has changed. What has changed is what I can do compared to when I was younger. Injuries, four operations, two herniated disks and a knee that will need replacing soon, all contribute to adjusting, modifying, adapting your waza to compensate for your physical limitations. Maybe it created different possibilities. There is a greater need to truly find the path of least resistance – or utilizing an approach that doesn’t require simple muscular strength. One of the reasons I go for the face (atemi) on tenshinage or irimi is because I am not going to load some huge guy on my back. If they don’t want to fall; then boom! in the face.

Sensei I am not sure that you really changed much over the years in that manner…

you always had a very practical approach. Thinking back to the comment on the declining membership in Aikido – Seagal gave it a relevance that it seems to have lost. There are still instructors who can demonstrate the budo of Aikido, but the current vogue in the States is for an effective martial art.

I really dislike this discussion on what martial arts are effective and which are not. I find them so ludicrous. In an era when everyone has guns, nothing works. Hey MMA guy, bang! you are dead.

Firearms are undeniably a valuable life-safety tool. So if pure efficacy isn’t your goal, what is?

I love the opportunity to have an object (uke) that I need to move, manipulate, immobilize in the most efficient way possible without inflicting undue harm, and have the opportunity to play with the various or even unlimited ways to do that. Yes – Aikido is like grammar and it is generative. How many times can you do the same thing the same way until you are bored senseless?

Kyoto Aikikai has become a true destination for Aikidoists from around the world. Okamoto sensei has truly become an inspiration to many.

Aikido Kyoto is her baby. I help teach a few times a week, both children and adult classes and fill in when she is travelling, but she runs the show. Sometimes she teaches three classes a day. I may be skilled at pedagogy but Yoko has a great ability to see each individual student and know what they need to develop.

At Aikido Kyoto, we have really developed a community – and an international community at that. Forty-percent of our enrollment is foreigners and from a variety of countries. We have students who range in age from 4 to 75. The trick is how to maintain a high standard of training and be able to assimilate and accommodate such a wide range.

That is an amazing accomplishment.

Yes, Yoko had really come into her own. It has been an interesting process to observe. I can’t even pinpoint when it happened, but she has become very popular; maybe one of the most influential Aikidoists in the world today. She has come into it rather reluctantly though. I think she finally realized that, as a woman, if she doesn’t step up then who will? She has an amazing ability to sustain herself and minimize injuries. She has a remarkable constitution. In 6th grade she received the ‘most healthy child’ award from Kanagawa prefecture. In terms of her Aikido, it is always evolving.

You already described how your Aikido has changed, but when I look back it seems to me that your Aikido has remained more consistent over the years than Yoko’s. It is hard for me to describe – but I guess ‘truer to your core’ would be a phrase. I try to eschew poetic images but more a river bank and less a river. Both the bank and the river change over the years but the bank develops through removal more than process change. Despite your own evolution sensei – you continue to provide that framework – the deep structure that allows for generative Aikido.

_________________________________________

[1] Klickstein later became a subject of much controversy.

[2] Michio Hikitsuchi (1923-2004) trained with O Sensei before WW2 and built the Shingu Kumano Juku Dojo at O Sensei’s request in 1953 where he continued as its chief instructor until his passing in 2004. The controversy on his promotion results from O Sensei’s verbally awarding him 10th dan in 1969 but the rank was not processed through normal organizational channels.

[3] Mitsuzuka sensei – see Japanese Swordsmanship by Don Draeger. In addition see >here<

_________________________________________

The underlying rules of language. An amusing reminder for native speakers of English:

There are rules to the structure of language – just as there are rules of motion.

This is great stuff. Thank you Chris and Ty Sensei for sharing not only your stories but your teachings.

LikeLike