Serendipity: two seemingly unrelated sources collided to shape this reflection.

In Billions, a well-written drama series I binge-watched through season 2, Axe and his wife Lara are on the verge of divorce. When she hires a rival hedge-fund manager to audit her husband’s fortune, his lieutenant Wags resists showing her the trading history. Axe interjects: “Lots of people watch Bruce Lee movies. It doesn’t mean they know karate.” Knowing the trade record isn’t the same as reproducing the strategy.

Around the same time, I read an essay contrasting Founding vs Inheriting, summed up in one line:

We can also think of this as read-only culture, the ability to repeat what an ancestor has handed down – but not recreate it from first principles.

That line completed the circle. Watching Bruce Lee ≠ knowing karate; inheriting ≠ founding. The distinction is between replication and re-creation. And nowhere is that divide clearer than in martial arts.

The traditional teaching methods of many arts are exactly that: traditions; passed down, replicated, unchallenged. In this read-only culture, the art survives, but in a desiccated state: drained of necessity and therefore of meaning.

To preserve a form is not to understand it. To understand it is not to originate it. The teacher’s challenge is to lead students through all three levels of understanding.

The first task of a teacher is replication. Faithfully preserving and perpetuating form is essential, and difficult enough.

The second task is refinement: laying out a path for progress. At this level, the role of a teacher is to illustrate tips and tricks to further developmental progress. The first part of developing talent is avoiding doing anything stupid. Avoiding stupidity is easier than trying to be brilliant. Instead of asking, “How can I get better?” you should ask, “What’s hurting my progress most and how can I avoid it?” Identify obvious failure points, and steer clear of them. That is to say, the best teachers use various means and methods to develop a student’s skill.

At this level there are concrete pedagogical dictums. Show the flow but also provide opportunities for slow deliberate training (tanren). Why? Because precision is the key component to instill and speed, or velocity, is last component to emerge as flow, as a consequence of precision. And the pursuit of precision is the pursuit of excellence.

And the final task is inspiration: to breathe life into what has been learned, to make it generative again.

In Excellence, I followed Will Durant’s assertion that excellence is a habit: Establish the right habits in order to work continuously towards excellence – progress through continuous training. Although a good coach can drive player performance through demanding training and a brilliant coach can instill a purpose, ultimately, the drive to excel is inspiration.

Inspiration – to breathe life into something.

Dwell a bit on the implications of that phrase. Through our words and actions, teachers must provide life imbuing motivation. Great teachers can do that. But how?

Perhaps it results from my current course of reading, but the cliché “it’s not the destination but the journey” isn’t sentimental nonsense; it describes the dopamine system. What do I mean by that?

Cognitive psychology shows that the brain’s reward circuit fires not at attainment but at pursuit. The satisfaction lies in moving from A to B, not in being at B. Hence the belt system: concrete milestones sustain motivation, transforming a lifetime path into achievable segments. Cynics see a business model; psychologists see neuro-architecture. The hierarchy also re-creates dominance order, our primal way of measuring progress within a tribe.

In short getting somewhere isn’t necessarily what people want, because once you get there, you have to get somewhere else. The paradox: once you arrive, the reward fades. The tide recedes.

Therefore, the teacher must design a contradiction: discrete attainments that confirm progress, yet a goal so lofty it can never be reached. The pursuit of perfection is the mechanism of motivation. Set an impossible ideal, and the dopamine circuit never closes.

Ah, but how does one make a transcendent goal appear achievable so as not to short-circuit the system and de-motivate students who recognize the impossible standard?

I have no concrete answer.

At this time, all I can suggest is that the next level of transmission is ensuring students understand the purpose behind the forms. Understand and show bunkai so that the forms have a concrete purpose.

In closing, a quote intended to inspire:

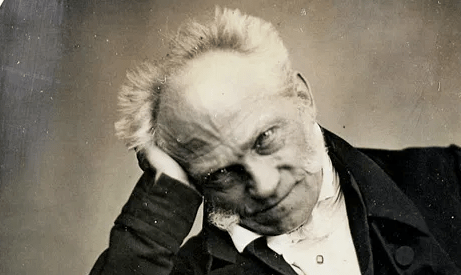

Talent hits a target no one else can hit. Genius hits a target no one else can see.

Arthur Schopenhauer

The teacher’s task is to make the unseen visible, so the student, too, can aim at what does not yet exist.