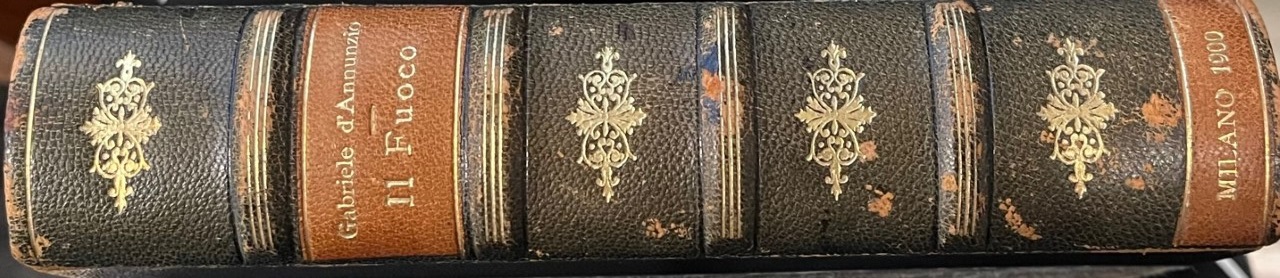

Before he died, my uncle Tony gifted me his first Italian edition of Il Fuoco (The Flame, 1900), signed by Gabriele D’Annunzio himself.

I regret that I didn’t record where or why he acquired the book.

He did teach himself Italian, but I don’t know if he mastered it sufficiently to read the original. I cannot read Italian and had to content myself with the English translation and internet searches to read the work and better understand D’Annunzio.

D’Annunzio was born in 1863 to a plebian family but was given a Jesuit education, which provided him the classical tropes he used in his later verse, which tended to the erotic, to the great appeal of his countrymen. He was a poet of the senses and most fervently of the pleasures, and pain, of love, which documented his own Rabelaisian lifestyle. He pursued the opposite sex with insensate fury. Isadora Duncan [1] documented his several attempts at her in My Life and concluded, “That was the genius of D’Annunzio. He made each woman feel she was a goddess in a different domain.”

Of all his relationships, his liaison with the celebrated actress Eleonora Duse, had the most dramatic effect on his life and art. During their nine years together (1895–1904), she inspired him to write his major poetic and dramatic works. He paid her back with a series of infidelities that culminated with the publication of his thinly veiled confessional in which he portrayed her as a has‐been. But the real treachery occurred when he gave a drama written for Eleonora to Sarah Bernhardt, “her one and only rival,” to perform.

The biographical context provided historical depth to a novel that is florid and so sentimental that I can barely choke it down. The emotional tenor is on overdrive, as if every character is constantly consuming MDMA. It’s all art all the time and every encounter can trigger a revelation that shudders the soul.

They felt that in that one moment they had lived beyond all human limits, and that before them was opening a vast unknown, which they might absorb as the ocean absorbs, for, though they had lived so much, they felt their hearts were empty; though they had drunk so deep, they were still athirst. An overmastering illusion seized upon these rich natures, and each seemed to grow immeasurably more desirable in the other’s eyes. The young girl had disappeared. The expression of the despairing, nomadic actress seemed to repeat: “Embrace me wholly, and my love will render thee divine! One hour, one single hour with thee, and I shall be saved! Mine for a single hour! Thine for a single hour!”

(Perhaps I should give D’Annunzio a pass – his passages reminded me of Lovecraft’s purple prose of the unimaginable horrors. D’Annunzio is enjoying the bawdy life that Lovecraft denied.)

D’Annunzio considered himself Nietzsche’s superman and Henry James was inclined to agree, “Ostensibly, transcendentally, his is the most developed taste in the world. … Beauty at any price is an old story to him; art and form and style as the aim of the superior life style are a matter of course.” I am not sure Henry was as astute as his brother William (and I agree with Daniel Robinson that William was the better writer). D’Annunzio seems to have used his art as a means of seduction not transcendence. A hedonist, he used his fame to immerse himself in every kind of luxury. He built a soundproof thinking room filled with velvet cushions in his villa overlooking Florence where he wore lace underwear and mink‐collared robes, only forsaking them for the brown habit of a monk when working on a new project. His voluptuary habits bankrupted him so he fled his creditors for France.

Fortunately for D’Annunzio, The Great War gave him a new stage. In 1908 he had flown with Wilbur Wright, so he returned to Italy to become a fighter pilot. The war for him was a live-action play. His Wikipedia page sums it well:

In February 1918, he took part in a daring, if militarily irrelevant, raid on the harbour of Bakar (known in Italy as La beffa di Buccari, lit. the Bakar Mockery), helping to raise the spirits of the Italian public, still battered by the Caporetto disaster. On 9 August 1918, as commander of the 87th fighter squadron “La Serenissima”, he organized one of the great feats of the war, leading nine planes in a 700-mile round trip to drop propaganda leaflets on Vienna. This is called in Italian “il Volo su Vienna”, “the Flight over Vienna“

The war was his rebirth: the libertine became the Übermensch. He gave balcony speeches that contained all the elements of the Nietzschean tradition — will, sensuality, pride and instinct.[2] In 1919, with the war at an end, D’Annunzio led the invasion of Fiume. It was more a parade than an invasion, but for fifteen months he was comandante over his coastal kingdom.

He lived as he wrote; overwrought and loud. Until he was bombarded into submission, he was the dictator of Fiume. Most critically, consider closely how he solidified power: he coauthored a constitution that played to the crowd (nine corporations representing the productive sectors of the economy) with the tenth to represent superior humans. He declared that music was the fundamental principle of the state. This is Nietzsche’s love-affair with Wagner politically embodied. He knew how to play the masses with symbols and speeches and was brutal enough to strongarm opponents with blackshirted followers.

Mussolini was a rival (and I suspect played a role in D’Annunzio’s 1920 defenestration) who adopted all D’Annunzio’s tactics – politics as theater. Who better than a poet and playwright to script the strategy? One should argue that Niccolò Machiavelli wrote the rules of engagement 400 years earlier in The Prince. But as sound as Machiavelli’s advice is, the spectacle is missing: D’Annunzio knew the stage before he knew politics. Machiavelli was just a diplomat who taught the evils of power.

As a novel, Il Fuoco, doesn’t seem to be my uncle’s flavor. (I remember him saying he didn’t see Pretty Woman because it glorified prostitution.) Perhaps the repressed sexuality of a New Englander was given relief because written in Italian (when in Rome…). I suspect some of his interest could have been salacious, but the greater interest was historical. D’Annunzio’s importance as a literary figure would have been less interesting than his role in history. I share that belief. D’Annunzio’s poetry and prose are of that time, but his political contribution has deep repercussions.

In the United States, Trump spring-boarded from The Apprentice to the presidency with the pussy-grabbing, tax-evading, aplomb of a true hedonist: A very plebian version of D’Annunzio’s life as art (Chappelle’s honest liar). Then Trump rallied his blackshirts on January 6th in an attempt to retain power.

And in Italy, Giorgia Meloni‘s ascent is seen as a resurgence of fascism and she did (at age 19) proclaim Mussolini was good leader. But if Meloni is able to hold a coalition, she will only be head of a country with a declining population, systemic corruption, and crippling debt. She (and Italy as a country) is beholden to the EU central bank. The danger she can do to Italy could be profound, but the danger she could do with it on the world stage is trifling.

That is not the case for in America. On November 15, some guy in Florida announced he would again run for the office of president. De Tocqueville saw the fragility of the American experiment in 1835, and he saw it clearly. The character of key election officials held in 2020 and saved the experiment. I fear that the abject stupidity of the many and the incredulity and cupidity of a few may cause its collapse.

Whatever the prerogatives of the executive power may be, the period which immediately precedes an election and the moment of its duration must always be considered as a national crisis, which is perilous in proportion to the internal embarrassments and the external dangers of the country. Few of the nations of Europe could escape the calamities of anarchy or of conquest every time they might have to elect a new sovereign. In America society is so constituted that it can stand without assistance upon its own basis; nothing is to be feared from the pressure of external dangers, and the election of the President is a cause of agitation, but not of ruin

Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, Volume I

Let us hope De Tocqueville is proven correct once more in 2024.

____________________

[1] Isadora Duncan died because her silk scarf, draped around her neck, became entangled around the open-spoked wheels and rear axle, and pulled her from an open car. While tragic and horrific, her death has a twinge of the comic reminding me of The Incredibles: No Capes!

[2] I proffer the prosaic presentation of Nietzsche – a glorified individualistic power-grabber: An individual that shall take and keep what he can and who believes that it is false consciousness to play at altruism and to encumber ourselves with hypocrisy. The Nazi corruption and simplification of Nietzsche where power has rights of conquest; that a chosen race is entitled to all the advantages accruing from conquest. Thus D’Annzunio lives in this mode of obtaining from life all that it has to give. Art is his watchword, the art of life is his text. Know the beautiful, enjoy all that is new and strange, be not afraid of moral law and of human tradition for they are idols wrought by the ignorant. I do not subscribe to this hedonistic interpretation of Nietzsche. The true Übermensch needs to become a god unto himself: to set forth goals and creation-affirming actions independent of an adherence to empty tradition. God is dead. That places the crushing burden of independence upon the Übermensch. It is not the ultimate freedom from rule, but the inexorable need for self-rule: which is a far more difficult task than obedience.

Who doesn’t like a nice fountain pen signature?

LikeLike