In The Knowledge Illusion, Steven Sloman and Philip Fernbach argue that the mind has evolved to do the bare minimum that improves the fitness of the host – one could insert cynical observations on the obviousness of this given the general lack of critical thinking skills …

The authors draw on evolutionary theory to demonstrate that because humans are a social species who collaborate highly, abilities have been ‘outsourced,’ resulting in a diffused intelligence where people individually store very little information in their heads. Good economists and social scientists will not be surprised by the general conclusion because robust networks are always distributed broadly and among specialists with competitive redundancy. As demonstrated years earlier, not one person knows how a pencil is made.

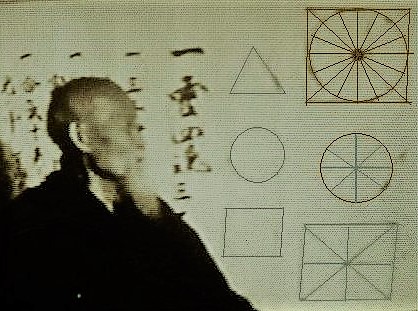

There are numerous conclusions to draw, but as it pertains to the principles of motion, the analogy is: no one teacher and no one art contains all the information necessary to achieve mastery. Or perhaps phrased differently, to unlock the principles contained within each art we may need keys from other arts.

While training in Okinawa Kenpo, I was bemoaning the number of kata and the number of steps in each so I asked my teacher, “why does the art have so many (and seemingly unrelated) kata?” The wisest answer I ever received: “Only ten-percent of karate works, but you will never know which ten-percent works for you until you learn it all.”

I also remember Necomedes Flores telling me, “Aikido is like a laser” – he was drawing a distinction that Aikido honed in on and isolated just a narrow range of motion, whereas Okinawa Kenpo was closer to a ‘shot gun’ approach – encompassing a wider array. The differences in approach gives truth to “there are many paths but one destination.”

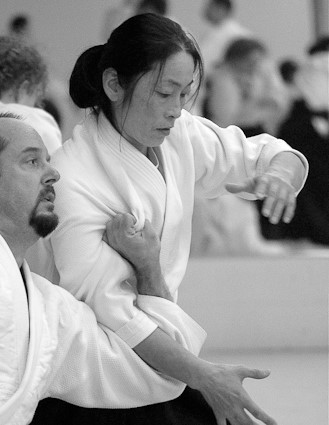

This leads back to ‘unpacking’ kata dori. We have been focusing on the importance of understanding ranges of attack using a very specific form – the shoulder grab. Last class we started with the static contact and basic (kihon) technique – a short step with atemi followed by a flanking step and arm control: what I have labeled a ‘box step’ for the simple analogy that expressed in its full range, the feet will traverse a square. But that is a mere teaching convention. We focused on the physical sequence of action to ensure that it is correct because done out of proper sequence, the tension drops which exposes nage to a counter. So proper sequencing.

The exercise to learn proper sequencing. Both players must be willing participants in the game. Uke grabs firmly and with a natural heaviness (but not resisting, otherwise nage should apply an impactful atemi). Nage responds by keeping the tension in play and drawing uke in by using the back leg as the muscular column to initiate the movement (the front leg is free and could be used as a front snap kick, but that isn’t the point). Once the back leg is ‘loaded’ tori should be drawn toward nage (this is the kuzushi, or destabilizing action). Continuing to experience uke’s weight, nage then steps directly back then sinks into an extended iai-goshi-esque position with the back leg now out in full extension. Uke has been drawn forward and down to be thrown by nage’s balanced acceleration. I cannot emphasize enough that this is an exercise that allows uke to experience the draw and for nage to feel which parts of the body must be engaged muscularly (stable core) and which are relaxed (resist using your shoulders).

From the lineal exercise we can introduce the second vectors and the hip rotation. The shoulder draw exercise isolated the tanren portion of the technique, the atemi– hand begins to add the element of timing. At its most basic, the atemi is done as a direct half-step (a full step would necessitate a knee to the groin and full palm strike) hence the half beat (jab) where nage’s free hand executes a jab, brachial to elbow sequence. Remember that this hand is establishing one fixed point of tension that is vectoring toward tori’s center line while the shoulder hand is drawn back. Again – the kihon footwork is a half step forward, followed by a full lateral flank followed by a full step forward. The more advanced timing is to invite uke in – meaning the shoulder is grabbed, but rather than allow uke to establish weight, nage uses a straight (not angular) atemi while executing an ushiro tenkan step and using the atemi and shoulder vectors to continuously de-stabilize uke. Because nage’s shoulders and lines of force are moving in opposite directions while the front foot is stepping back, uke will look as if he is being pulled with a rotational energy. This is not the case. Both combatants initially play a straight line – At its most effective, the kata-dori to atemi sequence is expressed similar to an in-quartata motion. It is only because uke avoids the initial eye-spear and by moving the head away, off line – starting what will now look like a circular movement. Adamantly, nage should not start to “blend” for if you do, you will expose the opposite flank to a quick counter.

In the next stage of timing, nage now closes maai as uke grabs. Nage’s atemi and footwork must now be in perfect time. As uke grabs, nage advances irimi, executes an eye-spear, brachial to elbow hit and then back to the carotid line. This three-beat attack with the free hand forces uke’s head back and the elbow up, allowing for the grabbed shoulder hand to flow low to high and control uke’s elbow. I also demonstrated the low line (invisible) kick as nage moves irimi to add yet one more point of contact.

From the advanced lines of play, we explored different beats – as the timing becomes ‘more perfect’ nage should be able to do a two-beat (free-hand to elbow then grabbed shoulder hand to elbow) and then a one-beat (grabbed shoulder hand to elbow only). And then we isolated the grabbed shoulder to show the use of that hand alone. This changes the overall line of motion to ashi-sabaki. The grabbed shoulder hand executes a back-knuckle strike to the musculocutaneous nerve followed by a punch to the mandible. The ‘rolling’ use of the striking arm is similar to a proper ashi-sabaki arm pattern. From the strike pattern we then moved to a pure ‘snake’ which is executed in time without the need for an atemi sequence.

Unpacking the very ‘basic’ kata-dori attack with different responses in time and range, we begin to see the expansion of possible ‘techniques.’ The analogies (similar to, as if) and tricks imbedded in this exploration are drawn from multiple arts – keep exploring.