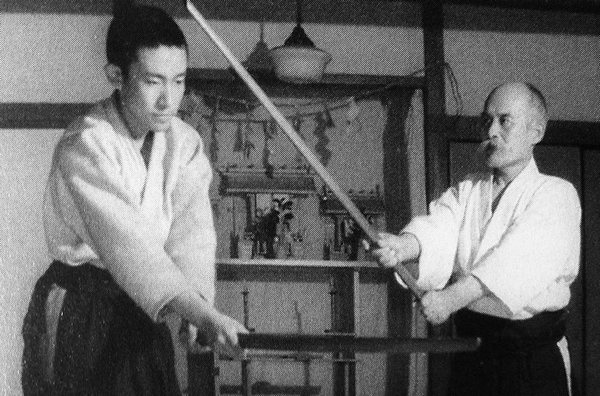

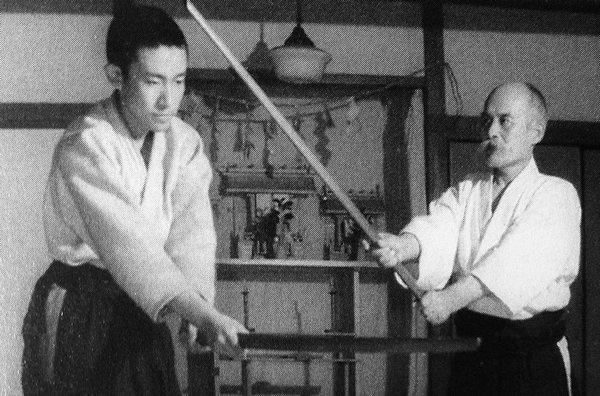

With the two basic ranges understood, let us focus again on shomen. The step-cut is ‘long range’ and the slide-cut is ‘short range’ but the ranges are also examples of time. Meaning the longer the range the more time tori has to respond. In order to train the correct response, we focus first on the longer range. With a proper and decisive shomen, the correct response is not to use a cross-block arm and focus on the distal part of the arm, but rather to use the opposite (usually the back) hand to stop uke’s striking arm at the triceps. Simply stated, gokyo’s entry. However the refinements are as follows.

For simplicity – focus on a right handed shomen. Arrest the strike in proper time with your left hand from below on the triceps. Tori’s right hand is focused on the counter strike to uke’s head (which is always a viable target). Respecting the threat, uke’s attack is firmly stopped which allows tori the time (beat) to replace the left-hand control of uke’s strike to transfer to the right hand. This can look similar to ikkyo. However, rather than focus on uke’s arm, once the right-to-right contact is established, tori’s left hand then drops to strike uke’s femoral. In short, tori executes a reverse “c” cut hitting first uke’s offending (striking) hand then to the groin. Tori’s right hand game is a simple counter cut. Either of tori’s actions could succeed – and really it is immaterial which does. The idea of technique is a fine heuristic for teaching, but we are trying to move beyond techniques to derive principles.

To emphasize the principle, I will point out a long-taught fallacy regarding ikkyo omote. The focus on the control of the weapon (the invisible katana) and the wielding arm leads many students off the true path for years. Students struggle to control uke’s arm, which is free to move at the shoulder and contains the least amount of mass. Remember – the real weapon is your opponent, what they wield is a tool. Given that reminder, ikkyo omote is a secondary response when tori fails to simply strike uke first. Ikkyo is a back-up play, not a primary response. As a secondary response that doesn’t mean it is of lesser importance. Just like the old adage that “two is one, and one is none” when it comes to preparation, we all need to have programed back-up scripts to play when our primary ones fail to achieve the necessary results. So if the primary goal is to counter-cut, and the secondary is ikkyo, the tertiary play is the reverse c-cut I described above. These are all permutations on a timed response to an overhead strike (or even a properly delivered yokomen – remember we are at close range here).

Another principle to derive from the reverse-c is to remember that tori’s control over uke is on the vertical axis, not on the horizontal line. At close range, uke largely dictates the horizontal line of play: uke attacks which closes the horizontal distance. Tori however has full freedom on the vertical line of play (hence passata-sotto among other ‘techniques’). Wherefrom these concepts? Armed combat, which was the origin of the gamut of Aikido techniques, but as I have stressed so often: no one art, culture or time has the monopoly on the universals. Technique is derived from principles. Principles are delimited by the human body and its responses to physics and physiological limits.

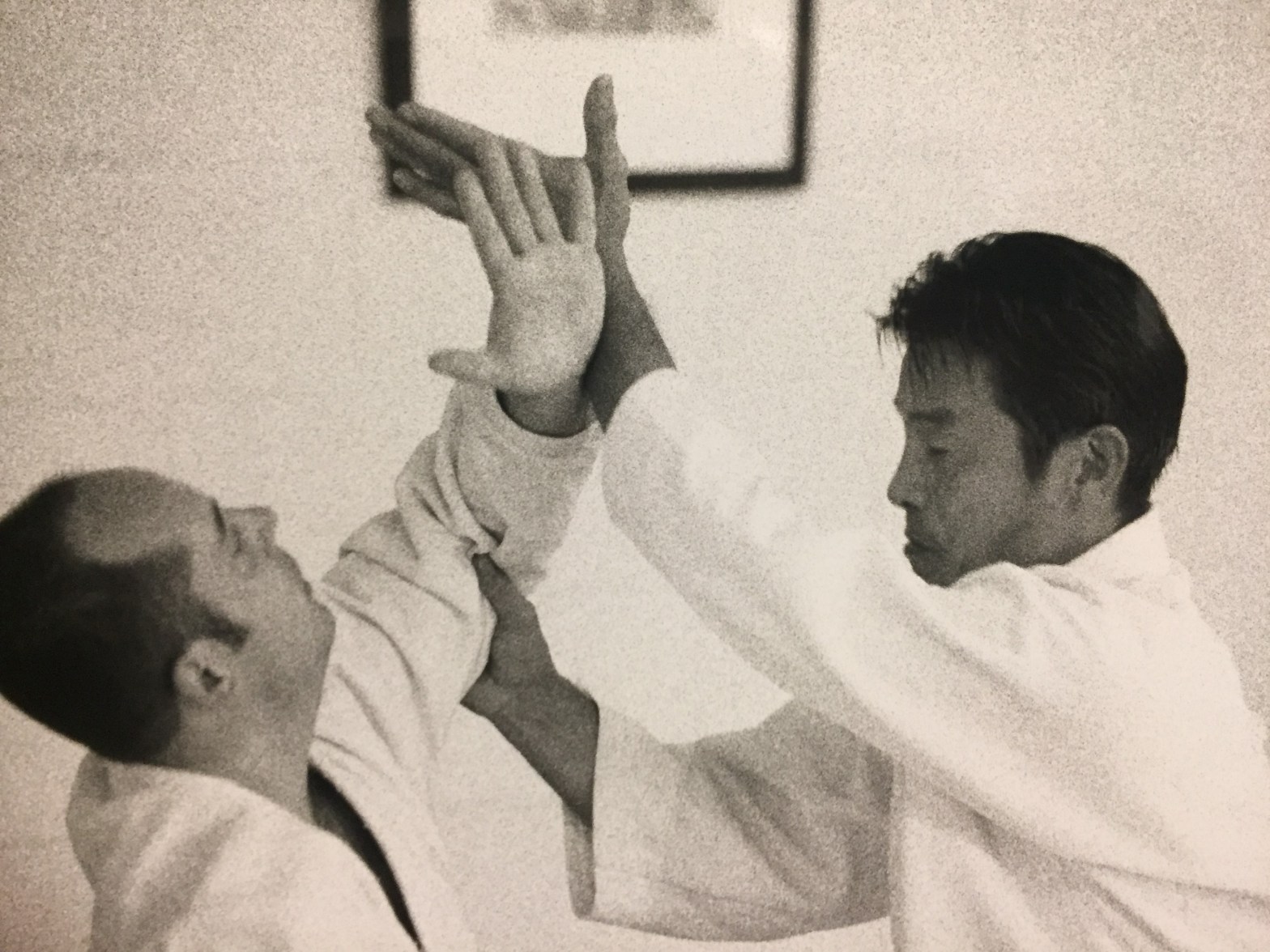

After exploring the ikkyo inside line, I then introduced kokyu-ho but from the inside line. How does this work? Again for simplicity, let us review uke delivering a right hand shomen strike. Tori responds at first with a right hand cross but the left hand will quickly become ‘primary’ as a finger spear to the eyes (combatively) or a palm cover (in training) that effectively blinds uke to the lower body’s play. The lower body stays on the inside line, which means tori’s groin is exposed to uke’s lead leg. But is it? Remember tori is closing the gap by advancing also which puts tori’s left leg on the outside of uke’s right. As tori’s left hand ‘rakes’ uke’s head, tori’s left leg can either reap or brace for a leveraged throw. The threat of a kick is largely nullified by uke’s strong intention to strike (you cannot execute a genuine cut and kick simultaneously) or if the strike is a ploy, tori can always ‘cover’ his crotch with a quick closing-cross of his legs. Most males do this instinctively anyways. The effect of a cross will be to buckle uke’s lead leg in most instances. Add the bunkai of a foot trap to the encounter and uke’s ankle will break.

Please note that this ‘technique’ is a genuine form of kokyu-ho. Just one played from the inside line and not the outside. So the primary difference will be that tori’s hand will be palm down and elbow up, whereas kokyu-ho on the traditional outside line is performed palm up and elbow down. So, please keep training the ‘basics.’ The traditional form of gyaku-hanmi, tenkan, kokyu-ho with its correct emphasis on lower body control, soft shoulders, dual-vectoring of forces to instill proper tension, and diaphragm controlled breathing and foundational skills to develop. These are the necessary forms of individual and internal development necessary to execute techniques and deploy the derivatives that form the compass of principled movement.