Let me state unequivocally that I am not an advocate for violence. However, in my experience, it is imperative to understand how to employ violence since that is the only way to ensure we are training properly.

Hence taking examples, training methods, and being influenced by other arts that focus on pragmatic and effective deployment of violent skills. And this includes taking lessons from modern self-defense skills like handgun training.

Memorizing patterns will only lead to the inability to act when the patterns are disrupted. Learning choreography is an important first step to executing technique – but it is not the goal. In training have you ever noticed that if uke attacks with the ‘wrong’ hand or has the ‘wrong’ foot forward that your technique is disrupted and your mindset disturbed? Be honest. It was. Hence exposing the limitations of a set pattern memorized in response to the staged attack. You have just experienced a ‘real’ attack and recognized a limitation of training. Without the ‘proper’ cues and context, ‘technique’ becomes more difficult to execute.

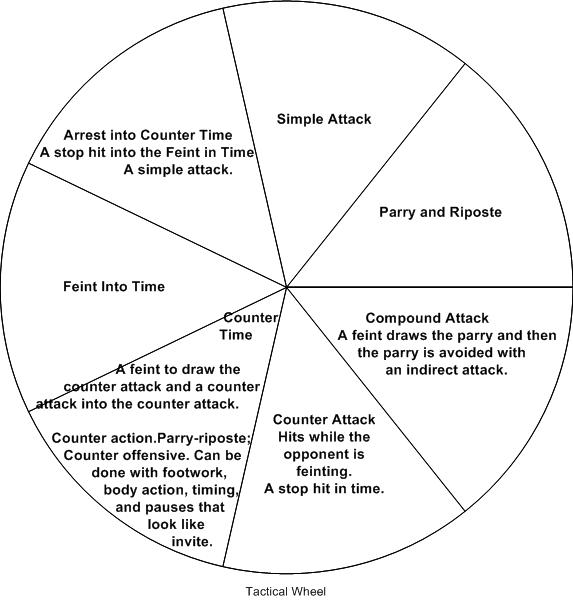

In part, this is why I am inserting ‘reactive’ training drills and other means of ripping apart a ‘technique’ – changing its tempo, adding half beats – in order to ensure that the responses we are learning become more ‘universal’ so as to contend with the chaos of reality. This stuff works outside the dojo if we allow it to. All of these missives are my attempts to provide ideas on how to break beyond the routine training. It really is a mind-set change more than a method change. And the mindset is really breaking apart the ‘trade off’ mentality of nage vs uke – we focus on ‘technique’ as nage and on ‘ukeme’ as uke. I hope it is becoming clear that for more advanced students, once the rudimentary knowledge of ‘how to fall’ is learned then the focus should start to be an analysis of ‘where am I as uke vulnerable?’ and then blossom to ‘how do I become nage?’

I found an old kaeshiwaza matrix I built for myself to arrange a class I gave for our mat fundraiser. I attached the outline for your review, but I think the introduction is really the most important part: there is no uke in a combative art – I purposefully used tori to indicate the change in mind-set, because too often uke is in essence the person who ‘lost’ the encounter. Because uke is taught ‘how to take’ ukeme it becomes an exercise in training to lose. We can use phrases like – maintain connection, etc. – and they are important concepts, but ultimately it must become a mentality to survive and reverse. There is no uke in a martial setting.

Hence the dangers of ‘teaching’ kaeshi waza as a ‘technique’ because it is an encouragement to resist and reverse. So again – the admonishment against ‘competition’ is valid. Rather, I would encourage the mind-set of constantly focusing on openings/opportunities. We must conduct training in a spirit of serious play – testing each other respectfully: are there openings? Expose weaknesses with a commitment to making each other better. In sparring arts, the light contact free-spar environment allows this development. Because our art focuses more heavily on the trapping/locking range the ‘free spar’ is potentially more dangerous. The only variation between fighting and training is that in training you don’t actually main or cripple, but the movement pattern should be the same: otherwise, you are training to fail.

I have used the phrase ‘artifact of training’ usually to imply a ‘bad’ conditioned response. I am trying to avoid as much as possible in advanced students the ideas of limited context: in a ‘real’ situation you do this, but in the dojo you do that; if there were a knife it is done this way, but without one we do it that way. Too many paradigms to lock our responses. Contrast this with a ‘fighter’ mentality which simply enters and strikes – the only difference between the dojo and street is the amount of force deployed.

In this I would harken back to Aristotle’s (Durant’s) contention that excellence is a habit – meaning we act rightly not because we have virtue, but because we have acted correctly and do so repeatedly. Our training should embody the same goals – to make correct responses habitual. Part of that habit is target acquisition. The idea of finding ‘openings’ in nage’s technique while you are uke and as nage to employ proper targeting.

Striking a specific target, not a general one. There are several habits I see that must be driven out of Aikidoists. Using a palm to ‘block’ atemi. I have NO idea where this symbol of resignation was introduced but I adamantly LOATHE it. Fricking put your open palm between your face and my strike and it will simply be pinned to your head. Remember in my understanding ours is a weapon-based system therefore presume that every hand is weaponized and let that inform your training and responses.

That same concept should guide your waza also – meaning a generalized (non-specific) strike is a wasted motion – and wasted motion gets you killed. If you strike quickly and pull off target you are training to miss. It should be uke who responds and moves away from the force. You can only do this at relatively slow speed to get the feedback without injuring your partner. It also shows if you are in balance.

Rory Miller has interesting suggestions for training in slow motion – a turn-based action system – to allow participants to strike vital targets but safely because of the slow speed. To his point, no one slows down under stress.

The well-trained individual, I content, never sees himself as ‘training’ – they are always ‘fighting’ because it is a mindset. The victors mind, the will to prevail, the kill or get killed mindset. While this could be construed as aggressive or violent thinking, I suggest to you that it most effectively is not. Aggression is too easy to defeat because it telegraphs. We are seeking a ‘higher’ path, hence the connection to Zen, the no-mind, empty possibility. A warrior’s refined calm, not a berserker’s rage.

Perhaps defining some terms will help:

Practice = rote repetition

Concepts = mental tools for development

Techniques = crystalized concepts made mechanical

Like mathematics, there may be brute force ways to solve a problem, but we seek elegance.

Stages of development – there are three basic stages of development in the Japanese systems –

- shu (守?) “protect, obey” — traditional wisdom — learning fundamentals, techniques, heuristics

- ha (破?) “detach, digress” — breaking with tradition — detachment from the illusions of self

- ri (離?) “leave, separate” — there are no techniques or proverbs, all moves are natural, becoming one with spirit alone without clinging to forms; transcending the physical

I propose a Western matrix:

| Apprentice | Journeyman | Master | |

| Validation | Outside | Peers | Internal |

| Relations | Differences | Exceptions | Sameness |

| Rules | Follow | Play Within | Play With |

| Approach | Training | Practicing | Studying |

| Goal | Replication | Variation | Expression |

| Perspective | Specificity | Variety | Generality |

I borrow multiple concepts here. Bruce Lee’s aphorism that ultimately a punch is just a punch, inspires the developmental transitions. In short, as a beginner (an Apprentice) we seek a teacher – an outside authority to provide a path, we see and seek the differences among all the techniques (we collect them to learn them) and follow the rules (for they are in place to make a system effective) and replicate the actions/mechanics of the teacher and look for the specific forms that make our art unique. A more advanced student’s perspective would seek validation among their peers and see effective exceptions to the proper techniques and therefore can play within the rules of the art to find the richness of variety. This is an admirable achievement. Then there are those who seek nothing but internal validation and see the sameness of the arts – encouraging study and playing with rules because the goal is a refinement of the expression of movement and see that the range of motion is a universal.