The more I teach, the more I distrust my own methods. I vacillate between two instincts: to explain everything, the Western compulsion toward clarity, and to say almost nothing, as my Japanese teachers did. Both seem inadequate.

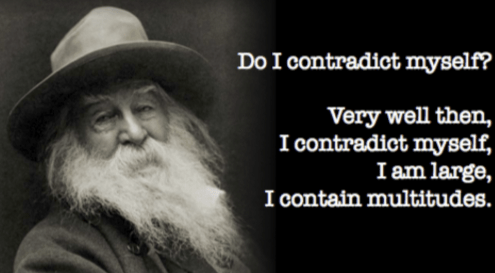

There is a paradox in learning that unsettles: The more effort one exerts to master, the more elusive it becomes. Aldous Huxley called it the law of reversed effort: the harder we strain to achieve a thing with conscious will, the more surely it escapes us. He was speaking of hypnosis and sleep, but also of prayer, meditation, and grace. It applies equally to Aikido; or to any discipline where body and mind must align without interference.

The promising student brings enthusiasm and the desire to “get it right.” But muscle and will can only carry one so far (Okamoto sensei assured me, this is sufficient through shodan). One must be able to replicate, with accuracy, the compendium of techniques, but their broader application and interconnectedness require more than rote understanding to perform under pressure, or in context. Where the instinct is to double down, to grip harder, to move faster, to strive, ultimately the need is less effort, less resistance.

In the Japanese tradition, we are given very little explanation. The teacher shows the form, usually four times or so. There is no breakdown, no step-by-step walkthrough. If we ask too many questions, the answer is often a nod toward the mat. “Steal it with your eyes,” the saying goes. You are not taught the technique. You must take it.

This is not a defect of pedagogy. It is the pedagogy.

Westerners tend to recoil from this opacity. We crave explanation, diagrams, logic chains. We mistake verbal description for understanding. Yet in Aikido, understanding emerges only when language fails (not a great prognosis for all my posts!); when the nervous system, not the intellect, begins to recognize structure. The body itself must learn.

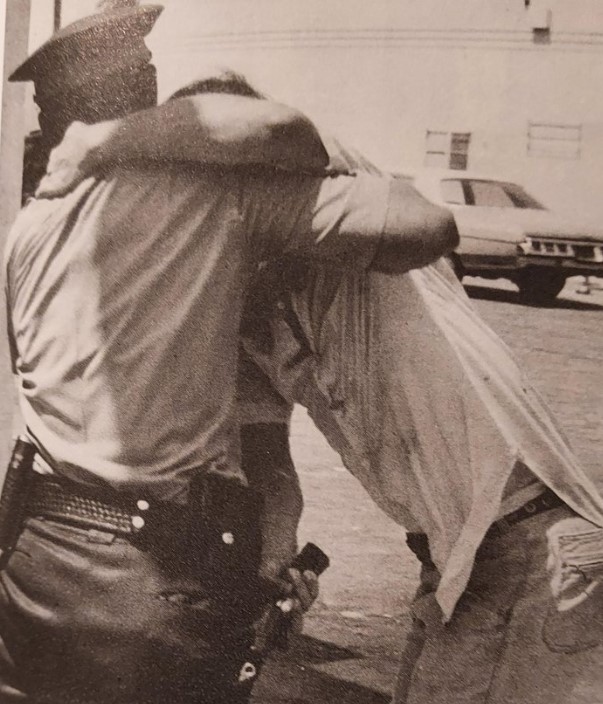

I’ve watched this law of reversed effort reveal itself most clearly when students are exhausted. After two hours of training, when strength is spent and ego deflated, their movement suddenly improves. They blend rather than resist; they feel timing rather than chase it. Not because they finally figured it out, but because they finally stopped getting in the way. Seminars can elicit this most easily, but every time on the mat is a chance to test your limits.

I had the fortune of learning under both methods, Mulligan sensei’s explicit and reductionist style and Okamoto sensei’s parsimonious approach to teaching. Later, after Chris and Yoko returned to Japan, I trained intermittently with James Keating. His approach could not have been more different. Keating offered a map (Keys to Effective Training) a set of organizing principles: quadrant play, logic chains, geometric patterning. His system gave names to what the Japanese left unsaid. It was cognitive scaffolding: an architecture for insight.

At first, these two pedagogies seemed oppositional. One relied on mimicry and patience; the other on analysis and categorization. But over time I came to see them as complementary expressions. Both lead, by opposite means, toward the dissolution of conscious will. The Japanese path exhausts the intellect through silence; the Western path exhausts it through complexity. Either way, the goal is surrender.

Keating’s “keys” are not commandments but instruments of revelation. They reveal structure so that structure can later be forgotten, like grammar to language, or kata to combat. Once internalized, the scaffolding collapses, and movement flows without thought. That is Huxley’s paradox again: will creates the preconditions for its own obsolescence.

Initially, and through every rank until shodan, we primarily progress through accumulation. But we deepen by letting go. I freely admit that I typically fail to “let go” and, therefore, am a poor model. But I see it. A subtle yielding replaces brute resolve. What once required ten thousand corrections becomes simple presence (shizentai).

Bruce Lee described this cycle perfectly:

“Before I studied the art, a punch was just a punch. After I learned the art, a punch was no longer a punch. Now that I understand the art, a punch is just a punch.”

The beginner imitates. The student analyzes. The master returns to simplicity. Complexity is not abandoned it is integrated, dissolved into instinct. The punch becomes itself again, but differently: empty of effort, full of intent.

If this sounds mystical, it isn’t. Neurophysiology confirms it: the prefrontal cortex quiets as skill automates; parasympathetic dominance replaces tension; the nervous system acts before the mind articulates. “Relax,” doesn’t mean be limp. It means stop interfering.

To master Aikido (any art, really), one must pass through both doors (back to Hulxley!): form and formlessness, prescription and freedom. In one, you think to understand; in the other, you move to remember. Each prepares the ground for the other. Together they form a single path: from effort to ease, from map to territory. Every true art moves this way: from accumulation to abandonment, from exertion to grace. We build the scaffolding to watch it disappear. We labor to exhaustion so that the body may finally remember how to move without us.