Timing and initiative are related concepts, especially once one steps onto the mat and is required to embody them rather than merely discuss them abstractly.

In my earlier article, Jo v Bokken article, I deliberately used traditional budō terminology, rather than exclusively use concepts from George Silver, Bruce Lee and John Boyd. That choice was intentional: the traditional terms deserve to be understood on their own terms before they are translated into other lexicons. What follows is an attempt to do exactly that.

The vocabulary of initiative emerges most clearly in early Edo-period sword theory, especially in the writings of Yagyū Munenori, recorded in Heihō Kadensho (c. 1632), and in the later tactical reflections of Miyamoto Musashi in Gorin no Sho (c. 1645).

Several points are immediately clear from these sources: Sen is not synonymous with speed. Acting early is often condemned as error. Initiative is taken after the opponent’s intention has fixed, not before it has formed.

Munenori repeatedly warns against premature action. The swordsman who moves too soon reveals intent without consequence; the swordsman who waits for fixation acts with inevitability. Musashi likewise emphasizes rhythm (hyōshi) and the breaking of rhythm to dominate the moment of decision.

What is notably absent in these texts is a clean taxonomy. The distinctions are present, but they are descriptive and situational, not codified into a pedagogical system.

The modern fourfold system (sen, sen-no-sen, go-no-sen, sensen-no-sen) is largely a pedagogical consolidation, refined through late kendo instruction.

| Term | Common Explanation |

|---|---|

| Sen | Taking initiative |

| Sen-no-sen | Acting as the opponent acts |

| Go-no-sen | Acting after the opponent |

| Sensen-no-sen | Acting before the opponent |

It is useful, but only if understood descriptively, not prescriptively. It does not tell you what to do. It describes when you when you are doing it.

Sen (先) Initiative Proper

At its root, sen simply means initiative. In classical usage, this refers to the moment the opponent’s commitment becomes readable and binding.

It is not attacking first, or moving quickly (speed), or forcing action. It is recognizing when the opponent has demonstrated intent and started along a trajectory and thus acting because the opponent can no longer recover safely (or change vectors).

Sen-no-Sen (先の先) Acting at the Moment of Commitment

Sen-no-sen describes action taken as the opponent’s initiative manifests.

Traditionally, this is the ideal timing: It is not preemptive, nor reactive, but coincident with fixation.

Structurally, this is the moment when the opponent’s attack is real, but its outcome is not yet decided.

In classical weapon systems, this timing preserves defense while seizing control. In budō, it became the model of “simultaneity,” though that term often obscures its precision.

Go-no-Sen (後の先) Initiative After Initiative

Go-no-sen describes action taken after the opponent has already initiated.

Classically, this timing accepts that the opponent has already seized advantage, and larger movements and compensation are required.

Both Munenori and Musashi acknowledge this timing as necessary, but inferior. The swordsman who relies on go-no-sen is already behind the decision curve.

Sensen-no-Sen (先先の先) Preemptive Disruption

Sensen-no-sen refers to acting before the opponent’s initiative fully forms.

In classical contexts, this often meant applying psychological pressure, threat, or provocation. (Watch early videos of O’Sensei and you will see numerous instances.)

Critically, because no commitment yet exists, this timing is structurally fragile. It relies on judgment, deception, or intimidation rather than inevitability. Used improperly, it puts you at risk, by moving first you show your intent and could over-commit.

So a fourfold system emerges that simply describes when one acts relative to the opponent’s irreversible commitment:

Sensen-no-sen — before commitment

Sen-no-sen — at commitment

Go-no-sen — after commitment

Sen — the condition of initiative itself

Again: this is not a tactical prescription. It is a descriptive ordering.

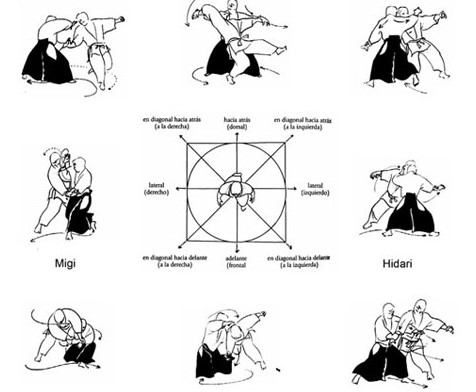

In Aikido, initiative correlates not to victory, but to the emergence of the axis of the encounter. The axis is the dynamic line of force, balance, and intent that emerges only at the moment uke commits and only where nage intersects that commitment.

Rather than seeking to end the fight, Aikido seeks to perfect the encounter. This requires a different emphasis for timing and initiative. Seen this way:

Sensen-no-sen occurs before an axis exists. There is no binding yet.

Go-no-sen occurs after the axis is already controlled by uke. Nage must compensate.

Sen-no-sen occurs at the birth of the axis. This is where Aikido’s internal logic is strongest. At that moment posture can be preserved (shizentai), movement becomes mutually constrained, and ki-musubi becomes perceptible.

Because these are descriptive labels and not prescriptive maxims, they are more neutral than other lexicons developed by fighters like George Silver, John Boyd, and Bruce Lee.

I discuss George Silver in an early post, but to provide a summary and contrast:

Silver does not speak of initiative. He speaks of combative safety. Silver’s “times” are not abstract tempos. They are priority rules of mass and threat:

| Element | Why it matters |

|---|---|

| Hand | Least mass, fastest threat projection |

| Body | Adds structure and power |

| Foot | Commits total mass, hardest to retract |

I frequently use Silver’s maxims in class, but his logic is what matters:

Actions that commit greater mass before threat is established are unsafe.

Thus:

Hand–Body–Foot → true time (threat first, commitment last)

Foot–Body–Hand → false time (telegraphed, unsafe)

This is exactly right. But why? Because Silver cares about survivability, not initiative.

| Silver Term | What it Actually Describes |

|---|---|

| True Time | Correct sequencing of threat → mass |

| False Time | Premature commitment |

| Measure | Whether contact can occur safely |

| Judgment | Recognition of opponent’s commitment |

Silver does not care who “goes first.” He cares who cannot safely change.

| Concept | Silver | Budō | Axis Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Commitment | Mass sequence | Initiative | Irreversible posture |

| Timing | True vs false | Sen categories | Axis emergence |

| Safety | Defense preserved | Harmony implied | Shared constraint |

| Error | Death | Technique failure | Compensation |

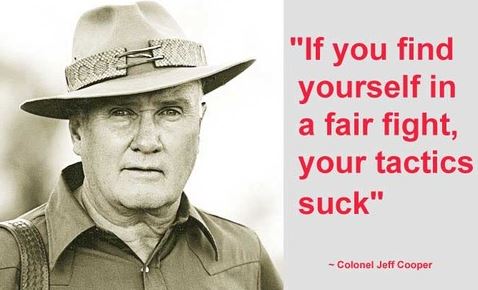

Silver and Col. Cooper speak the same language: employ the body with proper tactics. Budō speaks more abstractly. The axis model attempts to restore structural accountability without (necessarily) reintroducing lethality.

Perhaps the more interesting integration is an overly of Bruce Lee’s analysis of the Five-Types of Speed. In Tao of Jeet Kune Do, Bruce Lee breaks speed into five distinct but interrelated functions. These are not attributes of technique; they are failure points in perception and action.

- Perceptual Speed

How quickly one recognizes what is actually happening. - Mental Speed

How quickly one decides once perception is clear. - Initiation Speed

How quickly one begins action after decision. - Performance Speed

How quickly the body executes the chosen action. - Alteration Speed

How quickly one can change or abort action when conditions shift.

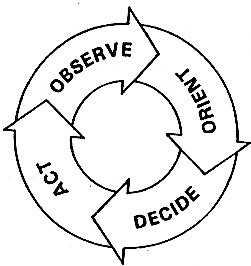

Lee’s taxonomy maps almost perfectly onto Boyd’s OODA loop, but at the scale of a physical encounter.

| Boyd (OODA) | Bruce Lee | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Observe | Perceptual Speed | Seeing what is actually happening |

| Orient | Mental Speed | Interpreting without distortion |

| Decide | Initiation Speed | Committing without hesitation |

| Act | Performance Speed | Executing physically |

| Re-orient | Alteration Speed | Adapting mid-action |

Lee’s genius was recognizing that most fighters fail before action: They see late, interpret poorly, hesitate, and then try to compensate with physical speed. Boyd would say the same thing (just with jets instead of fists).