Public virtue cannot exist in a nation without private, and public virtue is the only foundation of republics. But virtue must be vigilant lest it become tyranny.

-John Adams, Discourses on Davila

This Saturday (10/18/25), Portland filled with 40,000 protesters. The “No Kings March” is meant to remind those in power that sovereignty belongs to the people (We the People). I agree with the sentiment, but not the theater. Protests like this have become ritual consolations, moral pageants whose utility is their recursiveness, showing others of like mind that they are not alone. The Trump administration will not be swayed, and Trump relishes shouting the counter-narrative to justify sending in the National Guard. Still, I understand why people march. It is the same impulse that stirred my ancestors: the conscience of a free people bringing right order to the world.

When I trace my family line, from the Wadhams who fought in the Revolution and the Civil War, to the utopian Tafts and Messingers expelled from their pacifist commune for taking up arms, to the pragmatic Barkers who arrived later, I see an unbroken struggle between virtue and power. Every generation learns anew that moral men, convinced of their righteousness, do the greatest harm when armed with certainty.

The Tafts and Wadhams built their lives in the covenantal logic of New England Puritanism. They were farmers and soldiers who believed that conscience, bound by duty, was the only reliable governor of human affairs. When war came, first against King George, then against disunion, they fought for order grounded in consent.

The Taft and Messinger branches turned moral energy toward reform. Their flirtation with Adin Ballou’s Hopewell Community reflected a generational faith in perfectibility; an American translation of the ancient dream of virtue without violence. But the Civil War shattered it. When the call came, they left their communal experiment to defend the Union, earning expulsion from their idealists’ circle. I admire that decision.

The Barkers, who crossed from industrial England decades later, contributed a note of skepticism. The family motto, Fide sed cui vide, trust, but in whom take care, was not cynicism but experience rendered as caution. It has become my own watch phrase: trust but verify. They entered an America already rich in ideals and added the physician’s realism: every sickness demands diagnosis.

Herbert Hoover, though no relation, marks the hinge where private conscience first sought legitimacy through public administration; the moment when the moral impulse to serve hardened into the executive creed of coordination. His Quaker upbringing taught him that service to others was a sacred duty; his instinct was to save and to organize, to redeem suffering through coordination. That impulse first found expression in Europe. As head of the Commission for Relief in Belgium during the First World War, Hoover managed food for nearly ten million civilians, an unprecedented humanitarian effort conducted by a private citizen. In practice he acted as a quasi-sovereign, negotiating with both the British Admiralty and the German General Staff. The success of that moral enterprise convinced him that goodwill, properly organized, could substitute for government itself. Alas, he inverted the lesson once he was invested with the power of government.

When the United States entered the war, President Wilson appointed Hoover to lead the U.S. Food Administration under the Lever Food and Fuel Control Act (1917), which granted the president emergency powers to control agricultural production and prices. Wilson delegated those powers to Hoover personally, legalizing his moral voluntarism and transforming exhortation into administrative authority. The “Meatless Mondays” and “Wheatless Wednesdays” that millions observed were, in truth, the first national exercises in coordinated moral regulation; voluntary in tone, compulsory in effect.

As Secretary of Commerce through the 1920s, Hoover institutionalized this creed. He expanded the Bureau of Standards, promoted trade associations to self-regulate industry, and advanced the 1927 Radio Act, which established federal control over the airwaves, the new moral commons. His “associationalism” blurred the line between public guidance and private compulsion. In Ellis Hawley’s phrase, Hoover’s America became an “associative state,” where virtue was to be achieved by coordination, and coordination by administration.

Herbert Clark Hoover must be considered the founder of the New Deal in America… Hoover’s administration originated much of the fascistic central planning and coercion that Franklin Roosevelt later carried to completion.

Murray N. Rothbard, America’s Great Depression (Princeton, D. Van Nostrand, 1963), 464.

Rothbard meant it as indictment, not praise. Yet his phrasing proved prophetic: once moral authority legitimized administrative power, its growth became self-justifying. By the time of the Depression, Hoover’s faith in voluntary coordination had matured into national policy. The Reconstruction Finance Corporation (1932), the Federal Home Loan Bank Act, and the Emergency Relief and Construction Act all extended executive authority into finance and welfare. Each was presented as moral necessity, each as temporary expedient, and each survived him. Benevolence had become structural. Hoover was the first technocrat of virtue, deluded by the conviction that goodwill and information could substitute for freedom. Hayek would later show why this faith must fail: knowledge is dispersed, tacit, and perishable; it cannot be centralized without distortion (“The Use of Knowledge in Society,” 1945).

Hoover’s tragedy was that he acted from virtue. He mistook goodness for governance; the conviction that compassion could be legislated and that virtue, once nationalized, would ennoble rather than entangle. He was the first president to moralize efficiency, to treat coordination as a moral act. His failure was not corruption but faith that benevolence could be scaled.

Franklin Roosevelt and Rexford Tugwell “perfected” Hoover’s moral premise and institutionalized it. What Hoover proposed as volunteerism inspired by conscience, Roosevelt imposed in law. Tugwell called it “cooperation enforced by law,” a righteousness administered by bureaucracy. The New Deal transformed charity into regulation and compassion into command. It was the greatest encroachment upon individual liberty ever undertaken in the name of preserving livelihood. Once the state became the arbiter of compassion, every future crisis invited greater intervention. The Great Depression thus marked the true revolution: the substitution of civic agency with administrative benevolence. Thus was born the benevolent Leviathan. The Nanny State arrived not by force, but under a pretext of virtue.

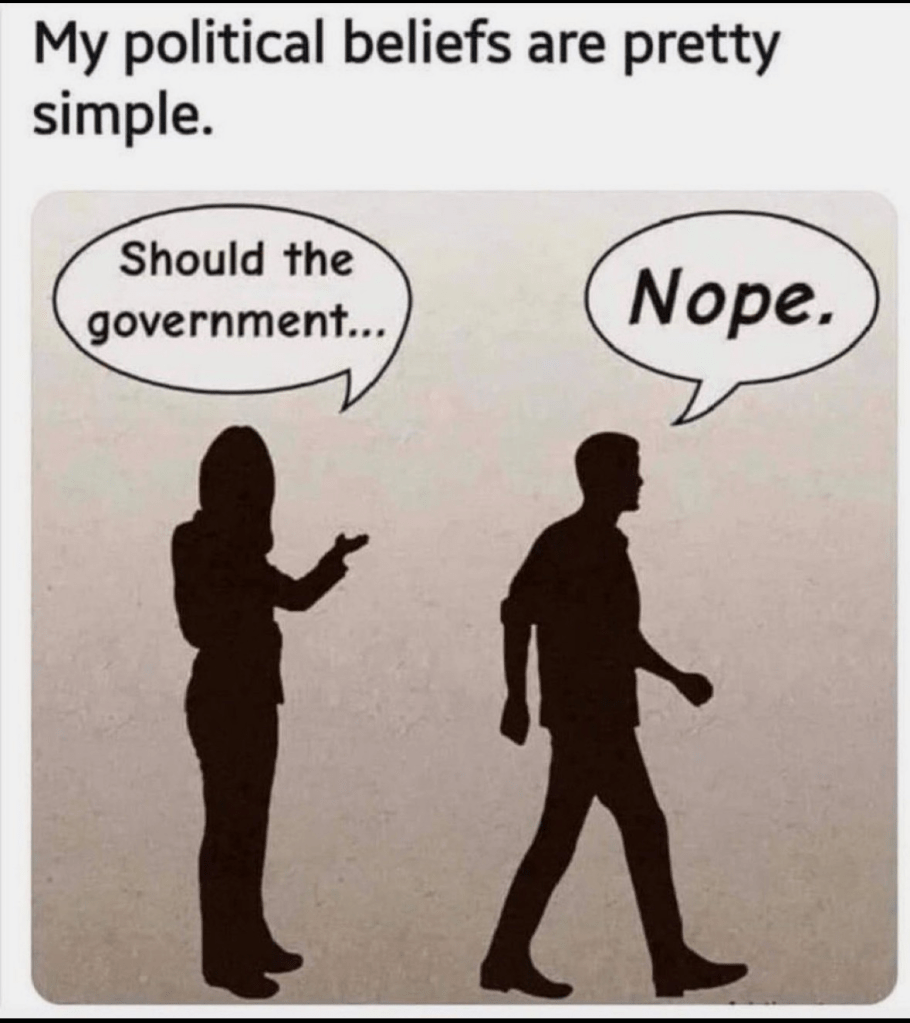

Each generation has repeated the same reflex. Lincoln saved the Union, Roosevelt saved capitalism, Truman and Eisenhower saved the free world. So runs the catechism of moral necessity that have become historical platitudes. And each salvation expanded the concentration of power. What began as Hoover’s Quaker instinct to help the common man evolved into the permanent conviction that “government should” solve whatever afflicts him. The citizen, succored by compassion, surrendered agency for comfort. To believe that government should do X, whatever X may be, is to accept that the state must hold the power to compel it. Every time we vote for virtue rather than practice it, we trade conscience for convenience. The serpent of moral governance always turns its head. If Acton warned that power corrupts, Spooner completed the logic: that even benevolent power violates liberty by definition.

A man’s natural rights are his own, against the whole world; and any infringement of them is equally a crime… whether committed by one man, calling himself a robber, or by millions calling themselves a government.

Lysander Spooner, No Treason: The Constitution of No Authority, No. VI, 1870

Lord Acton’s warning that power corrupts was too mild. Power moralized becomes irresistible, because it disguises domination as duty. The moralization of the past has become the perversion of the present: virtue no longer restrains power; it justifies it. Max Weber called this the routinization of charisma, the transmutation of moral fervor into bureaucratic routine.

The Anti-Federalists foresaw this. They feared that Rome’s fate would be ours: a republic of virtue collapsing into empire through perpetual emergencies. Madison in Federalist 51 tried to answer them (ambition would counteract ambition) but ambition now resides in a single branch. How did we get here?

Walter Russell Mead calls Americans “moral engineers,” a phrase meant kindly but tinged with prophecy (Special Providence, 2001). The moral engineer sees every problem as a design flaw. Lincoln, Hoover, Roosevelt, and today’s idealists share the same faith: that structure can redeem sin. It is a secularized soteriology; a Protestant impulse translated into politics. As Hayek and Oakeshott warned, the rationalist mind cannot grasp the organic order it disrupts. And that is the best prognosis; it assumes right-minded actors.

Thus, the futility of this weekend’s march. “No Kings” is a noble slogan, but we live in a kingdom of committees in the best of times, and under the current administration, one which recognizes that the constraints on power were always moderated by convention. Any actor willing to dispense with convention has power to wield without constraint. What protestors see as an abuse of power wielded by a singular man they happen to dislike (with good reason) is simply missing the point. The problem is not the actor; it is the concentration of power. As Tocqueville foresaw, the tutelary state does not enslave, it infantilizes.

I seek to trace the novel features under which despotism may appear in the world. I see an innumerable crowd of like and equal men who revolve on themselves without repose, procuring the small and vulgar pleasures with which they fill their souls… Above them rises an immense and tutelary power, which takes upon itself alone to secure their enjoyments and to watch over their fate. It is absolute, minute, regular, provident, and mild… It does not break wills, but it softens them, bends them, and directs them… it does not destroy, it prevents things from being born; it does not tyrannize, it hinders, compromises, enervates, extinguishes, and stupefies.

Tocqueville, Democracy in America, II.4.6, 663–664

And yet, history delivers its own ironies. When virtue exhausts itself in administration, power becomes brittle. A demagogue may do what reformers could not, expose the weakness of a government built on the illusion of goodness. Trump is no reformer; he tears down only to enthrone himself. Yet in doing so, he reminds us that the edifice of moral power rests not on law, but on convention. Once those conventions are despised, the people must decide whether to rebuild them or to reclaim what was theirs before the age of kings.

Trump has not drained the swamp so much as torn at its surface; in breaking norms, he exposes how deeply the system depended upon them. The assumption was that a bureaucracy endures because it is self-replicating, not self-limiting. Trump’s dismantling of the edifice exposed the fragility of its architecture. He seeks dominion, not renewal; yet in doing so, he reveals the extent to which our system depends on the moral habits of those who wield power. The citizen feels virtuous shouting in the street but fails to recognize that replacing this king with a benevolent one who restores the status quo ante is not returning power to the people. Lincoln’s war powers, Roosevelt’s alphabet agencies, the national-security state of the Cold War, all began as temporary expedients. None were repealed.

I find myself torn: I admire the marchers’ spirit, yet I know their indignation cannot touch the machinery they oppose. The republic survives not through noise but through virtue; the hard, quiet discipline of citizens who refuse both tyranny and spectacle. And when necessary, the citizenry effect change through violent revolution: a well-documented English tradition. My fervent hope is that armed rebellion is never warranted again. My hope is that the Trump abuse of power will remind America that its foundational documents were intended to prevent the very abuses we have witnessed in the long arc of the Republic. Each abuse had its moral justification, and perhaps in the moment it was necessary expedience, but once the crisis was resolved, the power was never returned.

If there is any lesson my ancestors offer, it is that moral courage must be matched by faith in people, and, when all else fails, the willingness to take violent action. The Wadhams fought because conscience demanded it, but they returned to their farms when the fighting ended. The Tafts abandoned utopia but did not seek to enforce another. The Barkers distrusted authority yet still served their communities. They understood something our modern moralists forget: liberty depends less on leaders than on citizens, who do not look to government to solve their own or society’s problems.

And yet despair would be another form of abdication. The duty of a free man is not to withdraw in disgust but to guard the small perimeters of autonomy still available (family, craft, locality, speech) and to model restraint when politics no longer can. The Anti-Federalists were right: only the virtue of citizens can prevent tyranny. Institutions cannot substitute for character. The republic is always one generation away from servility.

—Milan Kundera, The Book of Laughter and Forgetting (1979)

As I watched my wife don her inflatable costume to wear to the “No Kings” protest, I thought again of my ancestors. Their lesson endures: trust, but in whom take care. Power never returns itself. Every man who claims to save the republic diminishes it instead. The work of liberty is not salvation but stewardship; a patient vigilance that knows when help becomes harm, when virtue hardens into domination, and when we must relearn the grace of doing less. Stewardship is not passivity. My forebears knew that peace sometimes demands the courage to act; the tree of liberty, as Jefferson famously put it, must occasionally be “refreshed…with the blood of patriots and tyrants.” In extremis, that means armed resistance, the grim remedy of last resort. The subtlety, and the moral burden, is to know precisely when violence is warranted: only for a just cause, only after exhausting lawful and peaceful means, and with a realistic prospect of restoring liberty rather than perpetuating chaos. Resistance, when undertaken with such restraint, can itself be a form of care. A government worthy of a free people must always be fearful of them, for only then will public virtue remain tethered to private conscience.

References (selective)

Cole, Harold L., and Lee E. Ohanian. “New Deal Policies and the Persistence of the Great Depression.” Journal of Political Economy 112, no. 4 (2004): 779–816.

Ferguson, Niall. The War of the World. New York: Penguin, 2006.

Hawley, Ellis W. The Great War and the Search for a Modern Order: A History of the American People and Their Institutions, 1917–1933. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1979.

Hayek, Friedrich A. “The Use of Knowledge in Society.” American Economic Review 35 (1945): 519–530.

Hayek, Friedrich A. The Road to Serfdom. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1944.

Hoover, Herbert. American Individualism. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1922.

Kotkin, Joel. The City: A Global History. New York: Modern Library, 2005.

Kundera, Milan. The Book of Laughter and Forgetting. Translated by Michael Henry Heim. New York: Knopf, 1980.

Mead, Walter Russell. Special Providence. New York: Knopf, 2001.

Oakeshott, Michael. Rationalism in Politics and Other Essays. London: Methuen, 1962.

Romer, Christina D. “What Ended the Great Depression?” Journal of Economic History 52, no. 4 (1992): 757–784.

Rothbard, Murray N. America’s Great Depression. Princeton: D. Van Nostrand, 1963.

Spooner, Lysander, No Treason, Vol. VI: The Constitution of No Authority, 1870.

Temin, Peter. Lessons from the Great Depression. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1989.

Tocqueville, Democracy in America, II.4.6, 663–664

Tugwell, Rexford G. The Democratic Roosevelt. New York: Doubleday, 1957.

One thought on “No Kings”