Because they were educated on the West Coast, my children were taught next to nothing about the original colonies beyond the reductionist claim that the Pilgrims were “colonizers,” a word now used less as description than as accusation.[1] They learned to dismiss the charming saccharine gloss of A Charlie Brown Thanksgiving with knowing irony, and later guilt-shamed by an academic culture where convocations begin with ritualistic land acknowledgments.

The narrative I learned was a tale of noble dissenters. The Pilgrims were English Separatists sailing west in pursuit of “religious freedom.” I claim personal interest because my ancestors were there, and I too was told that they braved the Atlantic for liberty of conscience. But the truth is sharper. They were not apostles of tolerance; they were religious zealots who fled one hierarchy to found another.

Before their voyage, they had already fled to Leiden, Holland, where they lived under full religious toleration. Yet they feared that their children were becoming Dutch. John Bradford lamented that their sons and daughters were drawn away by evil examples:

But that which was more lamentable, and of all sorowes most heavie to be borne, was that many of their children, by these occasions, and ye great licentiousnes of youth in yt countrie, and ye manifold temptations of the place, were drawne away by evill examples into extravagante & dangerous courses, getting ye raines off their neks, & departing from their parents.

Bradford, Of Plymouth Plantation, Book I, ch. 4

Their flight to America was not an escape from persecution but a rejection of commerce and cultural looseness (Bangs 2009, chs. 3-4). They sought not freedom of religion but freedom for their own religion. They sought to build a theocracy of the elect.[2]

It was not an historian but a pulp writer who first showed me the effects of Puritan zeal. Robert E. Howard’s Solomon Kane, a wandering seventeenth-century Puritan who stalks the Old World with Bible and sword, convinced he is God’s instrument against evil, captures the same tragic fervor that animated my ancestors. Kane never sails to America but embodies the same theological conviction that crossed the Atlantic.

He is Puritanism stripped of congregation; pure conscience without the restraints of community, the zealot untethered from the covenant that once disciplined him.

Douglas Murray would read Solomon Kane as a symbol of the Western conscience turned inward; an almost pathological drive toward self-critique that becomes, ironically, a civilizational strength (Murray 2020, 87–92). The very zeal that fueled extremism also produced the habit of relentless moral self-examination, a trait David Hackett Fischer (1989) likewise notes in Puritan diaries and sermons.

Thus, they arrived in the new world as Calvinist exiles convinced they were chosen to build a better one. They read themselves into Exodus, imagining England as Egypt and America as Canaan. In that sense, their pilgrimage was not toward liberty but toward dominion, an audacious project to construct a purified society under divine law.

But first, they had to survive this brave new world. The first winter was brutal. Nearly half the settlers died from disease and starvation. In March 1621, the surviving Pilgrims met Squanto (Tisquantum), a Patuxet Wampanoag who had been kidnapped earlier by Europeans and learned English. Squanto taught them to plant corn with fish fertilizer, find edible plants, and survive in the New England environment:

Afterwards they (as many as were able) began to plant ther corne, in which servise Squanto stood them in great stead, showing them both ye maner how to set it, and after how to dress & tend it. Also he tould them excepte they gott fish & set with it (in these old grounds) it would come to nothing, and he showed them yt in ye midle of Aprill they should have store enough come up ye brooke, by which they begane to build, and taught them how to take it, and wher to get other provissions necessary for them; all which they found true by triall & experience.

Bradford, Of Plymouth Plantation, Anno 1621

In autumn 1621, after a successful harvest, the Pilgrims invited the sachem, Massasoit, and other Wampanoag men to join a three-day feast. Together, they ate venison, wildfowl, corn, squash, and other native foods. This feast became enshrined as the “First Thanksgiving,” a symbol of cooperation, gratitude, and cross-cultural friendship (Philbrick 2006, 57–92). Hence, the current holiday focus on hospitality and gratitude (and gluttony).

But the real story was more complex. What follows is the Paul Harvey version: the rest of the story.

When the Mayflower landed in 1620, the Wampanoag were not merely bystanders in a morality play, they were political actors making a high‑stakes gamble. The Wampanoag, Narragansett, and Pequot were locked in shifting rivalries over territory, tribute, and trade routes. Massasoit needed English guns to deter Narragansett incursions. Massasoit’s alliance with the English settlers was less about altruism than survival. It was an act of statecraft, forged under the pressure of epidemic, shifting power balances, and the looming threat of Narragansett aggression. David Silverman (2019) notes that this was an opening move in a fraught diplomacy that they hoped would stave off annihilation.[3] In his account, Massasoit’s alliance was as much a bet on keeping the English under watch as on welcoming them into the neighborhood. In this light, the “First Thanksgiving” is not a story of benevolent cooperation but of calculated risk. And it paid off for a generation.

When the Pilgrims arrived, the Wampanoag Confederacy was in crisis: a devastating epidemic between 1616 and 1619 (probably leptospirosis) had killed up to two‑thirds of their population.

They found his place to be 40. miles from hence, ye soyle good, & ye people not many, being dead & abundantly wasted in ye late great mortalitie which fell in all these parts aboute three years before ye coming of ye English, wherin thousands of them dyed, they not being able to burie one another; ther sculs and bones were found in many places lying still above ground, where their houses & dwellings had been; a very sad spectackle to behould. But they brought word that ye Narighansets lived but on ye other side of that great bay, & were a strong people, & many in number, living compacte togeather, & had not been at all touched with this wasting plague.

Bradford, Of Plymouth Plantation, Anno 1621

Neighboring tribes, especially the Narragansett of present‑day Rhode Island, had been largely spared and were growing in confidence and power. Massasoit faced a strategic dilemma: fight alone and risk annihilation, or seek new alliances (Silverman 2019, 26–45).

William Bradford records that the Pilgrims knew well that Massasoit was using them for protection:

And it is like ye reason was their owne ambition, who, (since ye death of so many of ye Indeans,) thought to dominire & lord it over ye rest, & conceived ye English would be a barr in their way, and saw that Massasoyt took sheilter allready under their wings.

Bradford, Of Plymouth Plantation, Anno 1621

Massasoit’s purpose was pragmatic: by binding the newcomers to his cause, he acquired both military deterrence and a diplomatic hedge. For their part, the half-starved and sickly Pilgrims needed allies who could help keep them alive. What emerged was reciprocal necessity, a compact of convenience.[4]

And for more than fifty years, this alliance largely held. The duration of the alliance is important to remember: it lasted longer than many modern geopolitical alliances last. The Wampanoag provided agricultural knowledge, food supplies, and diplomatic mediation with neighboring tribes. The Pilgrims provided firearms, trade goods, and a measure of deterrence against Narragansett and other rivals. Massasoit’s strategy worked. The Narragansett did not overrun the Wampanoag during his lifetime. Trade flourished, political marriages were arranged, and for a generation the two communities coexisted under a shared security framework. Nathaniel Philbrick calls this period a “mutual dependence that was pragmatic, not sentimental” (Mayflower, 2006).

Modern retellings often overlook this half-century of coexistence, a striking example of what Murray calls “selective moral memory,” in which periods of cooperation vanish while conflict alone is magnified (Murray 2020, 65–70). A more balanced account must register that the alliance endured precisely because each side pursued rational interests within a volatile field.

Bradford himself reflected on these beginnings with characteristic providential language:

Thus out of smalle beginings greater things have been prodused by his hand yt made all things of nothing, and gives being to all things that are; and as one small candle may light a thousand, so ye light here kindled hath shone to many, yea in some sorte to our whole nation; let ye glorious name of Jehova have all ye praise.

Bradford, Of Plymouth Plantation, Anno 1630

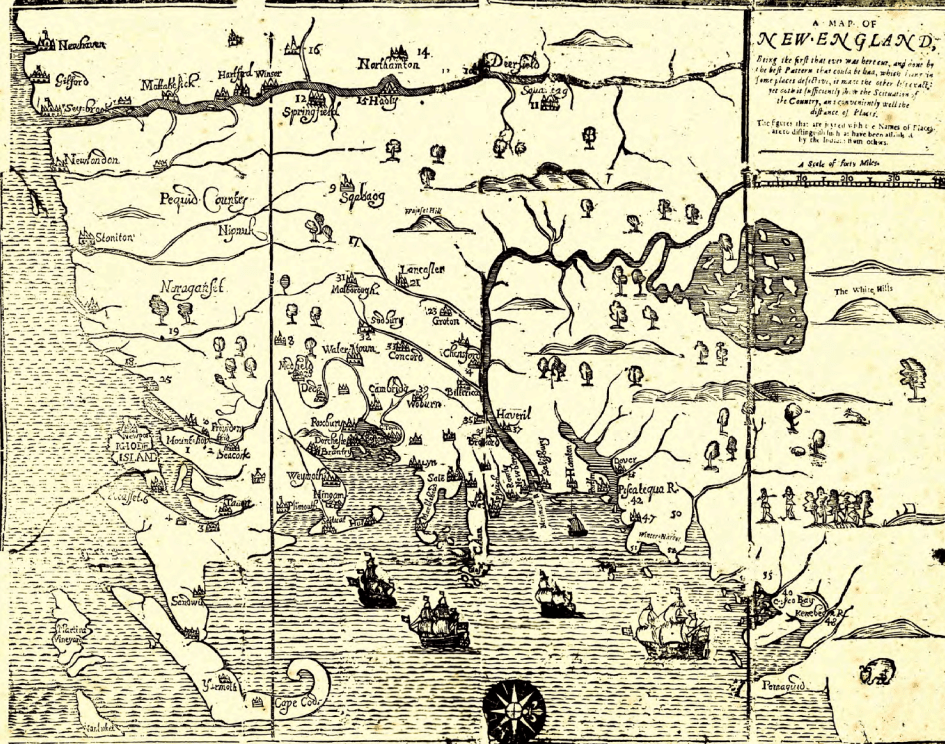

But over the course of fifty years, the light Bradford celebrated began to throw a longer shadow. What began as a single fragile outpost in 1620 was joined a decade later by John Winthrop’s fleet and the founding of Massachusetts Bay, a migration far larger and more deliberate, guided by Winthrop’s vision of a “city upon a hill.” English settlement grew, and with it, the balance of power tilted. By the 1670s, the Pilgrims’ descendants no longer huddled for survival but spread confidently across the New England countryside. The courts they built began to rule on disputes between Natives, and the appetite for land was avaricious.[5]

I see the origin myth through the lens of xenia, the Greek code of guest-friendship that governed relations between host and stranger. Like Odysseus welcomed by the Phaeacians, the Pilgrims were travelers on the edge of death, and Massasoit played the role of host-king who offers food, security, and recognition. Xenia was never just sentiment: it bound guest and host to reciprocal obligations of protection and alliance. The Wampanoag feast, like those in Homer, was as political, a public act signaling that strangers had been turned into partners. The tragedy of later decades is that this pact of xenia broke down; the obligations frayed, the reciprocity failed, and war followed.

It fell to Massasoit’s son, Metacom (mockingly christened ‘King Philip’ by the English) to face the consequences of his father’s bargain. The alliance his father had forged could no longer hold: English livestock trampled Native cornfields, land sales (sometimes coerced) shrank Wampanoag territory, and Christian missionaries chipped away at traditional authority. Fischer notes that Puritan evangelization was inseparable from political subordination; “praying towns” created parallel jurisdictions that eroded sachem authority and kinship governance (Fischer 1989, 259–266). From a Native perspective, this was not merely religious intrusion but a radical restructuring of sovereignty. Metacom concluded that diplomacy had run its course.

In 1675, war erupted.[6] What followed was the reckoning. King Philip’s War became the deadliest conflict per capita in American history. Over half of the English settlements in New England were attacked and a dozen were destroyed, and an estimated 3,000 Native Americans were killed, perhaps as much as 30% of the region’s indigenous population.[7] By its end, the Wampanoag Confederacy ceased to exist. Metacom was tracked through the swamps, shot and killed. His head was displayed on a pike at Plymouth for twenty years, a grim trophy meant to warn survivors. Contemporaries like William Hubbard and Increase Mather read the carnage as providence:

By all these things it is evident, that we may truly say of Philip, and the Indians, who have fought to dispossess us of the Land, which the Lord our God hath given to us, as sometimes, Jephthah, and the Children of Israel said to the King of Ammon, I have not sinned against thee, but thou do me wrong to war against me…

Mather, A Brief History of the War with the Indians in New England, 1676

Bradford, reflecting on earlier conflicts like the Pequot War, captured the cold clarity of that theology:

It was a fearfull sight to see them thus frying in ye fyer, and ye streams of blood quenching ye same, and horrible was ye stinck & sente ther of; but ye victory seemed a sweete sacrifice, and they gave the prays therof to God, who had wrought so wonderfuly for them, thus to inclose their enimise in their hands, and give them so speedy a victory over so proud & insulting an enimie.

Bradford, William. Of Plymouth Plantation, Anno 1637

Modern readers may recoil but Bradford did not. He inhabited a moral universe where Old Testament justice was mandate not metaphor.

Eric B. Schultz and Michael Tougias argue that King Philip’s War was the direct consequence of the fraying of the 1621 alliance; a classic case of a strategic gambit backfiring when the balance of power shifted irreversibly (Schultz & Tougias 1999). Their interpretation, though persuasive, still leans toward political inevitability. If Silverman emphasizes Indigenous agency and Fischer emphasizes English cultural inheritance, Murray forces us to confront the psychological machinery that made atrocity not only possible but righteous.

Howard’s Puritan wanderer, Solomon Kane, could have walked into this landscape without anachronism: the same moral absolutism now wielded muskets instead of swords. The colonial mind, like Kane’s, divided the world into elect and damned, covenant-keepers and heathen. Howard wrote fiction. The Puritans wrote history with gunpowder.

The burning of Simsbury in March 1676, one of several towns put to the torch, shows how far the war’s shadow stretched. Nearly every building was destroyed, leaving the town a blackened field. The settlers survived only by fleeing in advance, but the psychological cost was lasting: if Simsbury could burn, any town could. And when the war ended, the landscape itself bore the memory. Towns were rebuilt closer together and ringed with palisades; new garrisons dotted the countryside; roads were rerouted to link fortified posts. Native villages, where they survived at all, were pushed to the margins, their river valleys claimed for English farms. Christine DeLucia argues that such sites remained haunted landscapes: places where battlefields became hayfields and charred clearings turned into meetinghouses, even as the ground held the memory of what had been lost.[8]

Neal Salisbury describes this cycle as “borrowing European power,” a temporary gain that carries long-term risk (Salisbury 1982, 201–235). The tribes were not dupes of empire but practitioners of it. To ally, to bargain, to borrow European firepower were rational acts in a constricted world. Massasoit’s diplomacy was not naïve; it was brilliant. Its failure makes it tragic, not foolish. History does not punish stupidity as often as it punishes bad luck and demographic arithmetic.

Massasoit’s alliance was a wager that strangers with guns and scripture could be made into partners, and for a generation that gamble paid off. The Pilgrims survived, the Wampanoag held their ground against their indigenous foes, and for fifty years they lived under a fragile balance of power. That it eventually broke is not evidence that the compact was naïve or doomed, only that no alliance can outrun the shifting weight of demography, ambition, and fear forever.

And perhaps that is why Thanksgiving remains worth observing. Not as a moral fable, but as a study in risk and reciprocity. Survival was never guaranteed; prosperity always came with shadow. The Pilgrims were zealots, yes, but audacious ones, who planted a society that could argue with its own conscience. The Wampanoag’s gamble bought them a generation of peace. We may mourn the cost, but we can still honor the courage of the wager itself. Every light, if it endures, must learn to live with the darkness it casts.

In that darkness still walks Solomon Kane, a Puritan stripped of congregation and home, roaming the world with his Bible and guilt. He never reaches America, yet he is its premonition: the covenant turned inward, the city upon a hill reduced to a single restless soul. In him the Pilgrim’s audacity survives as obsession, the same fire that forged a nation and forever threatens to consume it.

America’s origins are not pure, but neither are they uniquely corrupt. They are the ordinary and universal human mixture of fear and aspiration, brutality and generosity, tribalism and transcendence. It is an odd inheritance, to be sure, but we might as well give thanks for it.

For we must consider that we shall be as a city upon a hill. The eyes of all people are upon us; so that if we shall deal falsely with our God in this work we have undertaken… we shall be made a story and a by-word through the world.

John Winthrop, A Model of Christian Charity, 1630

______________________________

I should credit Graeber for inspiring me to delve deeper into the impact of the Mayflower. Clearly, I am no fan of his, and his collaboration with David Wengrow in the ambitiously flawed The Dawn of Everything reminds us that Indigenous peoples were not passive recipients of European civilization but active thinkers and political agents whose critiques of hierarchy challenged European assumptions. Bravo. On this point Graeber is correct: Europe was not the only workshop of political ideas. But Graeber and Wengrow cannot resist romantically resurrecting Rousseau’s noble savage, arguing that Indigenous societies long experimented with political and social forms more egalitarian than Europe’s. This is Graeber at his most careless. As Ian Morris correctly criticizes in Against Method, a book about inequality that refuses quantitative tools ends up more rhetorical than analytical (Morris 2022:14). And Sumit Guha, in his review A False Dawn?, notes that sweeping cross-civilizational claims tend to collapse under inspection: The Dawn is “stimulating but flawed,” inviting the reader to fact-check every bold assertion (reminds me of later revelations of Foucault’s fabrications).

Fischer’s quantitative and archival rigor offers a useful counterweight to Graeber’s improvisational anthropology. Where Graeber imagines fluid, voluntary social structures, Fischer documents how inherited cultural patterns endured (Fischer 1989). The Puritans did not arrive as blank slates but as carriers of a deeply-formed and highly coherent worldview. So, while The Dawn usefully challenges juvenile “noble savage vs. colonizer” binaries, it tries to ensorcell a different enchantment: the romanticization of an ideal past.

Enter Howard’s Solomon Kane again, the Puritan’s ghost and Graeber’s perfect foil. Where Graeber’s imagined ancestors are cooperative, playful, and improvisational, Kane is rigid, joyless, and punitive: the other half of the human story. He is what happens when conscience eclipses curiosity, when the will to purity devours the capacity for play. In Kane is dark conviction of civilization that Graeber cannot quite account for, other than by making it uniquely Western. Kane represents the theological zeal that meaning requires judgment, that moral order must be enforced even at the cost of mercy. He gives the lie to the myth of unfallen humanity by insisting that evil is real and must be punished.

My thought takes a different line: humans are universally and equally imperfect and all human polities live in tension between creation and compulsion, strategy and violence. The Pilgrims did not arrive to a garden but to a contested field. Graeber imagines a primordial freedom; Kane reminds us that freedom without discipline collapses into chaos. Between them lies the very impulse of history itself; the alternating rhythm of exuberance and restraint, imagination and law. Thus always.

______________________________

[1] As Douglas Murray argues, modern moral discourse tends to flatten history into a prosecutorial narrative where Western actors are cast uniquely as villains and all others as passive victims (Murray 2022, 41–48). This reductionism obscures the reciprocal, often tragic choices of every society involved.

[2] David Hackett Fischer’s analysis of the Puritan “folkway” underscores this point: their overriding concern was not liberty as moderns conceive it but “ordered freedom” a disciplined, covenant-bound society where communal surveillance and moral regulation ensured stability (Fischer 1989, 134–172). In Murray’s terms, they were not proto-liberals but cultural maximalists, convinced that a virtuous community required narrowing, not widening, the range of permissible beliefs.

[3] Fischer reminds us that this diplomacy unfolded within a demographic imbalance that widened rapidly. The Puritan fertility rate, among the highest recorded in early modern populations, ensured that even a small initial settlement would soon outnumber Native communities still recovering from epidemic loss (Fischer 1989, 205–213). This demographic engine, more than ideology alone, set the long-term trajectory. It is important to note that Fischer shows each group arrives with minimal temporal or geographic overlap: Puritans arrive first (1620-1640) ~ 20,000 migrants from East Anglia settling in New England; then Cavaliers (1642-1675) ~45,000 migrants Royalist elite from south and west England (Wessex) to the Tidewater South; next the Quakers (1675-1725) ~23,000 filling the middle colonies around Pennsylvania; and finally, the Scots-Irish (1717-1775) ~250,000 from the Anglo-Scottish borderlands and Northern Ireland who settle Appalachia.

[4] The Wampanoag were not alone in this strategic pattern. In the earlier Pequot War (1636–1638) saw the Mohegan and Narragansett ally with the English to crush the Pequots, their rivals in Connecticut. The alliance succeeded (the Pequot were virtually destroyed, yet still own a major casino) but English expansion soon threatened the very tribes that had helped them.

[5] Fischer emphasizes that The Great Migration (1630–1640) brought not refugees but whole congregations who carried with them a pre-formed institutional grammar (Fischer 1989, 16–21). This was not chaotic colonization but “transplanted society,” arriving with expectations of ordered towns, disciplined churches, schools, and courts.

[6] The town of Mendon, Massachusetts, originally incorporated in 1667 as part of Suffolk County and later incorporated into Worcester County, was among the first English settlements attacked in King Philip’s War, and the first in Massachusetts Bay Colony to suffer casualties.

On July 14, 1675, a band of Nipmuc warriors ambushed several settlers in the outlying fields near Wigwam Hill, killing five men, including William Hackett and John Ball. A second attack followed on July 29, destroying much of the settlement. In the face of continued raids, the inhabitants abandoned the town entirely that summer, seeking refuge in Braintree and surrounding villages.

Adin Ballou summarizes the event succinctly:

Mendon was the first town in Massachusetts that suffered from the great Indian outbreak of 1675. The inhabitants fled, the houses were burned, and the place was desolate for years.

History of the Town of Milford, Worcester County (Boston: Franklin Press, 1882)

The same chronology appears in D. Hamilton Hurd’s History of Worcester County, Massachusetts (1889). Following the gradual pacification of the region, the settlers began returning to Mendon in 1679–1680. Among the early reappearing names in the town records is Robert Taft Sr., who had arrived several years earlier and is listed as one of the original proprietors whose home lot was later reconfirmed.

The Proceedings at the Meeting of the Taft Family at Uxbridge (1874) notes that Robert Taft was an early inhabitant of Mendon before the Indian War. The Taft homestead stood near the later border between Mendon and Uxbridge, an area that continued to serve as a familial nucleus long after the war. Robert’s perseverance through the destruction and resettlement places him squarely within the generation of New Englanders who experienced both the fragility and the moral consolidation of the early colonies.

[7] Hubbard’s Narrative of the Indian Wars in New England, is a full accounting of those early conflicts and shows the brutality of the combatants. Indian and Colonist alike shared a penchant for beheading…

[8] Here Fischer’s work is invaluable: New England’s reconstruction followed preexisting communal blueprints, militia districts, town commons, and covenant-based governance, that reproduced Puritan social architecture (Fischer 1989, 170–178). The very capacity to rebuild quickly owed to these transplanted folkways. Murray would argue that modern readers should acknowledge this institutional competency even while questioning its moral costs.

______________________________

Selected Bibliography

Ballou, Adin, An Elaborate History and Genealogy of the Ballous in America (Providence: E.L. Freeman & Sons, 1888) [Contextual notes on the Hopedale and Mendon families, pp. 40–43. A genealogical and local history resource with valuable context on Mendon-area families affected by King Philip’s War, including patterns of resettlement and communal reconstruction.]

Bangs, Jeremy D. Strangers and Pilgrims, Travellers and Sojourners: Leiden and the Foundations of Plymouth Plantation. General Society of Mayflower Descendants, 2009. [The definitive study of the Leiden Separatists’ intellectual, political, and theological world. Bangs dismantles myths of persecution and demonstrates that the Pilgrims fled tolerance, not oppression.]

Bradford, William. Of Plymouth Plantation, 1620–1647. [Primary source; indispensable for understanding Puritan providentialism, governance, and self-conception.]

Brooks, Lisa. Our Beloved Kin: A New History of King Philip’s War. Yale University Press, 2018. [Reframes King Philip’s War through Native geographies, kinship ties, and Indigenous voices. For an interactive website dedicated to her work >this< site is an well done resource.]

DeLucia, Christine M. Memory Lands: King Philip’s War and the Place of Violence in the Northeast. Yale University Press, 2018. [A study of how sites of war became landscapes of memory. I hate to admit I never learned about King Philip, so memory fades…].

Fischer, David Hackett. Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989. [A foundational work of cultural history arguing that four distinct British “folkways” (Puritan, Cavalier, Quaker, Borderer) shaped the regional cultures of early America. Fischer treats the Puritan migration not as scattered settlers but as the transplantation of a highly coherent social system, one defined by covenant theology, family discipline, literacy, communal surveillance, and “ordered liberty.” Fischer’s model explains why the Pilgrims’ zeal produced both intolerance and durable civic institutions: congregational governance, town meetings, written compacts, and a culture that prized accountability and moral regulation. Fischer grounds these traits in demographic, familial, and ecclesiastical data, making him essential for understanding the long-term structural power of Puritan culture.]

Howard, Robert E. Solomon Kane: The Complete Stories. Edited by Rusty Burke. New York: Del Rey, 2011. [This definitive edition restores all of Howard’s surviving Solomon Kane tales and fragments in chronological order, based on the author’s original manuscripts and Weird Tales publications. Burke’s introduction presents Kane as a Calvinist avenger whose faith becomes an existential burden: a lens through which Howard examined the moral ferocity and loneliness at the root of the Puritan conscience.]

Hubbard, William. A Narrative of the Troubles with the Indians in New-England (1677) [One of the earliest historical accounts of Native–English conflicts, revealing the theological framing of colonial violence.]

Mather, Increase. A Brief History of the War with the Indians in New-England (1676) [A providentialist narrative interpreting King Philip’s War as divine judgment.]

Metcalf, John G. Annals of the Town of Mendon, from 1659 to 1880. Feeman & Co, 1880. [Local history chronicling Mendon before, during, and after King Philip’s War.]

Morris, Ian. Against Method: Why the Liberal Order Is Under Threat and How to Save It. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2022. [A critique emphasizing the necessity of empirical and quantitative tools in historical analysis; valuable as a methodological counterpoint to Graeber.

Murray, Douglas. The War on the West. New York: HarperCollins, 2022. [Critiques the moral asymmetry of contemporary Western self-critique and the flattening of history into simple binaries.]

Murray, Douglas. The Madness of Crowds: Gender, Race and Identity. New York: Bloomsbury, 2020. [Analyzes how identity-based narratives distort public memory and historical understanding.]

Philbrick, Nathaniel. Mayflower: A Story of Courage, Community, and War. Viking, 2006. [Narrative history combining vivid storytelling with accurate treatment of the Pilgrims+Wampanoag alliance and its unraveling.]

Richter, Daniel K. Facing East from Indian Country: A Native History of Early America. Harvard University Press, 2001. [A work that re-centers Native perspectives, imagining colonial encounters as experienced by Indigenous peoples. Adds depth to the Wampanoag’s choices as strategic actors rather than passive victims.]

Salisbury, Neal. Manitou and Providence: Indians, Europeans, and the Making of New England, 1500–1643. Oxford University Press, 1982. [An ethnohistorical study showing how Native and European worlds intersected politically and spiritually.]

Schultz, Eric B., and Michael J. Tougias. King Philip’s War: The History and Legacy of America’s Forgotten Conflict. Countryman Press, 1999. [A detailed narrative history of King Philip’s War, emphasizing chronology, geography, and human cost. Strong on casualty data and battle descriptions to understand the war’s scale and stakes.]

Silverman, David J. This Land Is Their Land: The Wampanoag Indians, Plymouth Colony, and the Troubled History of Thanksgiving. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2019. [An authoritative work on Plymouth and the Wampanoag, interrogating the Thanksgiving myth and presenting Indigenous memory of the alliance and its aftermath.]

Taylor, Alan. American Colonies: The Settling of North America. Penguin Books, 2002. [A synthesis of early American history. Provides demographic, economic, and ecological background that situates Plymouth within a much larger story of colonization and exchange.]

Winthrop, John. A Model of Christian Charity (1630). Gilder Lehrman Institute. PDF of full text. [Foundational Puritan statement on covenantal duty and communal discipline.]

One thought on “Thanksgiving as Strategy”