In my 2022 post on Soylent Green, I traced how the film’s revelation, “Soylent Green is people,” dramatically literalized overpopulation as self‑consumption, a horror that lingers because it feels both absurd and, from an ecological perspective, plausible. That image was a cultural zygote: mutating into other forms of demographic dread across decades. In 2025, we look back not just at dystopian spectacle but at a longer narrative of how societies imagine, dramatize, and try to engineer population futures.

In 1968, Paul Ehrlich published The Population Bomb, warning of mass famine, societal collapse, and the need for coercive population controls.[1] The book became a media event. Ehrlich debated on television with an air of inevitability, and the Club of Rome’s Limits to Growth (1972) injected computer‑modeled collapse scenarios into mainstream discourse. Fiction tracked alongside: Soylent Green (1973) embodied overcrowding nightmares and Logan’s Run (1967/1976) imagined technocratic culling.[2]

What gave Ehrlich and the Club of Rome their wide acceptance was the migration of the ecological concept of “carrying capacity” into human affairs. The idea, rooted in Verhulst’s 19th-century logistic growth model (inspired by Malthus), was widely used by biologists like Eugene Odum. Wildlife managers spoke of the carrying capacity of a pasture for deer or cattle. By the 1950s, William Vogt’s Road to Survival (1948) had already applied the metaphor to humans. Ehrlich and the Meadows team amplified a frame already primed: humanity as herd, pressing against an ecological ceiling. Metaphor hardened into policy. NGOs and governments then implemented policy, most dramatically in India’s sterilization campaigns of the 1970s, before China made its own decisive turn. Charismatic leaders mislead; states coerce. The latter is always the more dangerous.[3]

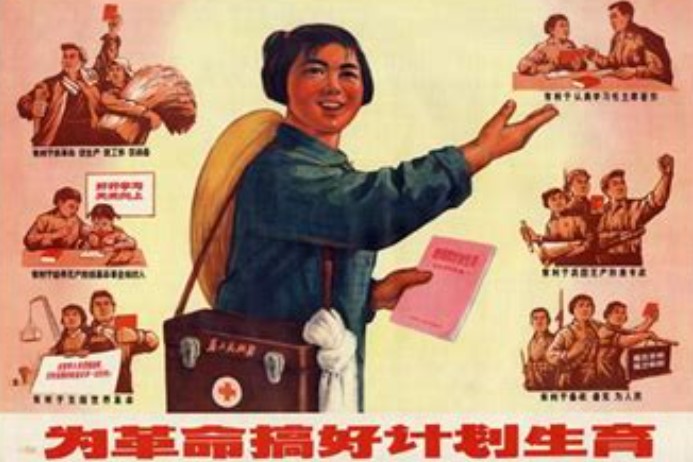

The most dramatic implementation was China’s one‑child policy. The ‘Later, Longer, Fewer’ campaign of the early 1970s already encouraged reduced fertility. Song Jian, a missile scientist, then applied cybernetic models to Chinese demography, projecting catastrophic overshoot absent drastic measures. Here the metaphor of carrying capacity was decisive. Song treated fertility like rocket trajectories: variables to be modeled, thresholds to be enforced. His charts gave scientific legitimacy to leaders already convinced that growth threatened modernization. By 1980, the one-child regime was coercively enforced through fines, propaganda, and, in many cases, forced sterilization or abortion. The legacy is a demographic hangover of aging, skewed sex ratios, and shrinking labor supply.

Ehrlich’s intellectual hubris of the over-population prediction cashiered on September 29, 1990. On that day he mailed Julian Simon a check for $576.07, settling their ten-year wager on the future of resource scarcity. In 1980, Ehrlich had staked his case on five metals—chromium, copper, nickel, tin, and tungsten—convinced their prices would soar as humanity pressed against the planet’s carrying capacity. Simon, betting instead on markets and ingenuity, predicted the opposite. By 1990, every one had fallen in real price, undone by discovery, substitution, and efficiency (Tierney, 1990). The wager stood as a proxy for the population crisis itself. Yet the predicted calamity was not overpopulation, just the great political famines orchestrated by Mao and Stalin.

The irony is that the Communist curtailment of freedom and the Western celebration of it both converge to a similar condition, what Nicholas Eberstadt calls the Age of Depopulation. Fertility collapse now grips East Asia, much of Europe, and reaches into the Americas: the alarm has reversed, from too many mouths to too few births.

The Western economic logic is straightforward. With declining infant mortality and higher income, families concentrate resources on fewer children. Gary Becker formalized this in his economic theory of fertility: children shift from economic necessity to hedonic expansion and sometimes a Veblenian display of wealth (“I can afford them”).[4] Yet behavior is not only economic but recursive. We learn from what others do. Dawkins’ memetics (the spread of ideas, habits, and norms) explains demographic swings as much as policy. In high-fertility eras, the skills of child-rearing and sibling care were learned across generations; in low-fertility eras, small families reproduce themselves culturally as well as biologically.

That suggests family size is not simply a response to incentives but a cultural competence that can be forgotten. If large-family formation has been unlearned, recovery may require more than subsidies. Sweden’s pro-natalist cycles suggest subsidies buy time but not permanence. A true return to replacement fertility would demand re-learning the rhythms, competencies, and social scripts of raising multiple children. In this light, the next demographic turn will come less from technocratic fiat than from memetic diffusion.

Demography may be destiny, but when governments impose demographic policy the results are disaster. Frank Herbert grasped this in fiction: that controlling sexuality and procreation is one of history’s most dangerous temptations. The Catholic Church understood it early; the message to “fructify the Earth” was joined with control of marriage and reproduction, producing a tool of population management and wealth accumulation.[5] Herbert saw the danger in treating human fertility as an equation to be solved, a temptation that carried Malthusian logic into empire and church alike. What Ehrlich and Soylent Green dramatized in the 1970s was ecological alarm; but it manifested, in China, as coercion. Today’s depopulation panic risks repeating the error in reverse: mistaking narrative urgency for policy inevitability. Without forced breeding, decline looks inexorable. The behavioral and economic logic of small families has been adopted broadly as a norm, memetic and recursive across much of the West. We appear to have cultural amnesia: the loss of the skill of family formation.[6]

____________________________

[1] For the 50th anniversary of The Population Bomb, Paul Ehrlich resurfaced on 60 Minutes and in The Guardian, insisting once again that the “collapse of civilisation is a near certainty within decades.” The prediction, repeated for half a century, now sounds less prophetic than compulsive. He still appears on small podcasts, warning of overpopulation, though the supposed Malthusian limit has migrated: not soil and food this time, but the destabilizing heat of agriculture and energy on the climate.

To his credit, Ehrlich is nothing if not consistent. To a biologist, the notion of carrying capacity is elegantly foundational, with powerful predictives. The difficulty is that he insists on applying it to humans, thereby ignoring culture and technology. Buckminster Fuller remains his best foil. Where Ehrlich sees limits as hard stops, Fuller saw them as design challenges. For Fuller, ingenuity is the decisive human trait, and pessimism nothing more than abdication. And so far, history has sided with Fuller’s wager: ingenuity has outpaced entropy. Ehrlich is a blinded cleric of Malthus, repeating the catechism even as the empirical gods refuse his prayer.

[2] Based on Matheson’s I Am Legend (1954), The Omega Man (1971) dramatized depopulation. The same cultural moment feared both excess and absence. Ehrlich warned of crowded streets; Matheson and Heston walked through empty ones. Soylent Green (1973) literalized Ehrlich’s nightmare: too many mouths consuming each other in a terminal economy of scarcity. The Omega Man (1971), put a twist to the panic, a plague leaving Neville the “last man,” with the survivors biologically transformed into a hostile mob. The fear was not of numbers but of the wrong people left, a mass rendered unrecognizable, anti-technological, and destructive of memory.

Then Silent Running (1972) offered the most ascetic parable: nature itself was the endangered species. Bruce Dern’s Freeman Lowell tends the last forests, sealed in domes orbiting Saturn, and when ordered to destroy them, he kills his crew and himself, preserving the trees by launching them alone into space. Where Ehrlich and Soylent Green framed humanity as the devourer of nature, Silent Running went further: humanity was the disposable element, the price worth paying to let photosynthesis continue.

Seen together, the trilogy dramatized the cultural logic of the early 1970s, the Limits to Growth (1972) moment and the origins of ecological awareness. Population, plague, and ecology became interchangeable metaphors for collapse. In one script, we choke on our own numbers (Soylent Green); in another, we are undone by transformation and plague (The Omega Man); in a third, we sacrifice ourselves to preserve the planet (Silent Running). All three share the same haunting backdrop: Malthus in new guises, asking whether the limit lies in land, in people, or in nature itself.

I imbibed the mythic origins, so the Greta Thunberg strikes me as a shrill tonal rupture. The ecological jeremiads of the 1970s presented ecological awareness as myth and consequence: nature as sacred, limits as parable, catastrophe as a solemn warning. Thunberg inverts that register. Her speeches frame climate change not as mythic inevitability but as political betrayal. “How dare you?” is not prophecy but prosecution. In doing so, she politicizes what was once contemplative, converting ecological awe into moral outrage. That shift is not a deepening of the myth but its perversion: a demand that awe be weaponized into grievance. Politicization is always an act of violence.

[3] Herbert’s caution was always double-edged. In interviews he said Dune was, at its core, a warning against charismatic leaders. A hero could seduce a people into surrendering judgment, and from there into tyranny. But the subtler danger, and the one more directly relevant to Ehrlich and the Club of Rome, is the state that arms itself with “scientific” inevitability. Once the metaphor of carrying capacity was transposed from deer herds to human beings, it offered bureaucrats and planners a language of necessity: limits, thresholds, overshoot. The danger was not merely being misled by a prophet but being coerced by a state that claimed biology as its warrant. In India’s sterilization campaigns of the 1970s, or China’s one-child regime of the 1980s, ecological metaphor hardened into fiat. Herbert’s prescience was in recognizing that once life itself is treated as an equation to be solved, the temptation to enforce the “solution” becomes irresistible. His warning about the hero thus extends to the apparatus behind him: charisma dazzles, but it is the state that compels.

On the ecological front, Herbert’s timing was uncanny. Dune predated the Club of Rome, The Population Bomb, and the cinematic panic of the 1970s. His ecological education was practical, tested in the Oregon dunes where he reported on federal experiments to stabilize sand with imported grasses. Walking those shifting landscapes with Wilbur Ternyik, he saw how human intervention could redirect wind and water across centuries. Howard Hansen, a Quileute elder, pressed him to take ecology seriously and gave him Paul Sears’ Where There Is Life, a book Herbert later said shaped his thinking as much as anything else. Sears’ maxim, that the highest function of science is to give us “an understanding of consequences,” echoes through Liet-Kynes. Other texts, like Leslie Reid’s The Sociology of Nature, with its portraits of tightly coupled resource cycles, provided academic insights Herbert could scale into planetary myth. By the time Dune appeared in 1965, his self-education had become a synthesis: Indigenous land wisdom, soil conservation practice, and mid-century popular ecology. While Ehrlich was still sketching famine graphs, Herbert had already written a myth in which ecology was destiny and fertility a lever of empire. He gave ecology the permanence of scripture, turning Sears’ warnings and the dunes’ lessons into parable. And parables endure longer than panic.

But Herbert was most prescient in his treatment of sexual energy. He saw eros not as subplot but as a civilizational engine. The Bene Gesserit reduced it to data, an index managed across centuries. The Fremen disciplined it into fertility for survival. The Imperium bent it toward loyalty and control. Again and again, Herbert dramatized the same temptation: to treat sexuality as just another ecological variable. Yet whenever the design seemed airtight, vitality burst free: through Paul’s love for Chani, through Leto II’s deviations, through Duncan Idaho’s refusal to remain a pawn. Herbert’s lesson is stark: sexuality is never mere indulgence; it is the most volatile energy of the species. Harness it, and you may steer history for a time. Try to master it completely, and collapse follows.

[4] Becker and Emmanuel Todd can be read as adversaries, but I view them as complements. Becker’s Treatise on the Family (1981) provides the economic “genotype”: households weigh costs and benefits, shifting from many children of necessity to fewer children of higher investment as incomes rise and mortality falls. Fertility collapse thus begins as a rational recalibration. Todd, by contrast, illuminates the cultural “phenotype.” In The Explanation of Ideology (1985), he maps family systems onto political structures: egalitarian nuclear families yielding liberalism, authoritarian stem families sustaining hierarchy, communitarian clans underpinning collectivism. In this frame, the same Beckerian household calculus expresses differently depending on the kinship culture that mediates it. A nuclear family system may interpret low fertility as a lifestyle choice; a communitarian system may absorb it into kinship solidarity; an authoritarian system may see it as threat to hierarchy. Becker explains the evolutionary logic of fertility decline; Todd reveals how that logic blossoms into divergent political orders. Read together, they suggest that the economic rationality of family life has cultural origins and that demographic decline is never just arithmetic, it is also ideology embodied.

[5] Genesis 1:28 commands humanity to “be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it” (KJV). The Catholic Church not only transmitted this injunction but institutionalized it. By the early medieval period, it had asserted jurisdiction over marriage, sexuality, and inheritance through canon law. Jack Goody (1983) argues that this “marriage and inheritance revolution” was not mere theology but a structural strategy: by prohibiting levirate marriage, consanguinity, adoption, and easy remarriage, the Church effectively redirected wealth away from extended kinship networks and into ecclesiastical hands. Widows and childless couples, deprived of kin channels, often donated property to monasteries, bishoprics, and ecclesiastical foundations. This gave the Church immense demographic leverage: control of fertility through sacramental marriage and control of patrimony through legal restriction. The economic consequences were staggering. By the sixteenth century, ecclesiastical holdings constituted a massive share of European land and wealth, which Henry VIII famously confiscated during the Dissolution of the Monasteries (1536–1541), seizing centuries of accumulated treasure.

[6] The economist Tyler Cowen has argued that America’s long-run prosperity depends less on preserving a perfect fertility rate and more on maintaining a dynamic inflow of people. In Average Is Over (2013) and later essays (2020), he stresses that immigration policy is the critical margin for sustaining innovation, labor supply, and cultural vitality in the face of domestic fertility collapse. For Cowen, the alarm is not famine but sclerosis: a society that forgets how to reproduce itself demographically and culturally must offset that amnesia by recruiting talent and energy from elsewhere. The United States, unlike East Asia or Europe, possesses the geographic and institutional openness to do so, but only if policy is intentional. The paradox is stark: family formation is a skill that must be re-learned, yet until it is, immigration becomes the substitute skill: imported vitality standing in for forgotten rhythms of reproduction.

Here Emmanuel Todd offers a counterpoint. His work shows that demographic systems are not just arithmetic but cultural blueprints, reproducing political orders across centuries. Assimilation succeeds only when newcomers adapt to the host kinship model: in America, the egalitarian nuclear family and the democratic individualism it underwrites. Cowen’s optimism thus depends on the very cultural confidence Todd insists is fragile. Immigration can buy time, but it cannot substitute indefinitely for a culture that forgets how to reproduce itself or if it allows in a people unwilling to adopt the host culture.

____________________________

Selected Bibliography

Becker, Gary S. A Treatise on the Family. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1981.

Club of Rome. Meadows, Donella H., Dennis L. Meadows, Jørgen Randers, and William W. Behrens III. The Limits to Growth. New York: Universe Books, 1972.

Cowen, Tyler. Average Is Over: Powering America Beyond the Age of the Great Stagnation. New York: Dutton, 2013.

Cowen, Tyler. “Why Immigration Is America’s Greatest Strength.” The Atlantic, January 2020.

Eberstadt, Nicholas. Men Without Work: America’s Invisible Crisis. Rev. ed. West Conshohocken, PA: Templeton Press, 2017. (See also Eberstadt’s essays on the “Age of Depopulation.”)

Ehrlich, Paul R. The Population Bomb. New York: Ballantine Books, 1968.

Goody, Jack. The Development of the Family and Marriage in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983.

Graziosi, Andrea. “Stalin’s and Mao’s Famines: Similarities and Differences.” East/West: Journal of Ukrainian Studies 3, no. 2 (2016): 9–34

Greenhalgh, Susan. 2005. “Missile Science, Population Science: The Origins of China’s One-Child Policy.” The China Quarterly, no. 182 (June): 253–76.

Herbert, Frank. Dune. Philadelphia: Chilton Books, 1965.

Logan’s Run. Directed by Michael Anderson. Beverly Hills, CA: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1976.

Longman, Phillip. The Empty Cradle: How Falling Birthrates Threaten World Prosperity and What to Do About It. New York: Basic Books, 2004.

Odum, Eugene P. Fundamentals of Ecology. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders, 1953.

Reid, Leslie. The Sociology of Nature. London: Penguin Books, 1958.

Sears, Paul B. Where there is Life. New York: Dell Publishing, 1970.

Simon, Julian. The Ultimate Resource. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981.

Soylent Green. Directed by Richard Fleischer. Beverly Hills, CA: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1973.

The Omega Man. Directed by Boris Sagal. Burbank, CA: Warner Bros., 1971.

Tierney, John. “Betting the Planet.” The New York Times Magazine, December 2, 1990.

Vogt, William. Road to Survival. New York: William Sloane Associates, 1948.