“Similia similibus curentur.”

— Hippocrates (attrib.), echoed by Paracelsus and Galen

Let like be cured by like.

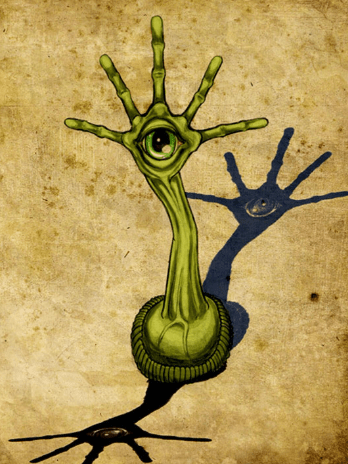

This principle, later adopted by homeopaths and ridiculed by modern medicine, remains as stubbornly persistent—and surprisingly insightful—as any ancient folk wisdom. You’ll find it not only in medical aphorism but also in the logic of sympathetic magic, as described by James Frazer in The Golden Bough: the belief that a small token of the harmful thing itself, properly administered, holds the key to healing (or beating the electric chair).

Pliny the Elder advised rubbing the ashes of a scorpion’s head into a scorpion sting. Ancient warriors smeared bits of rust from a cursed blade into their wounds to “pull out the evil.” The practice remains in common parlance after a hard night of drinking – the origin of “hair of the dog” is a contraction of:“Take a little hair of the dog that bit you.”

Perhaps we should not readily dismiss the idea, which as new scientific grounding, thanks to a series of elegant studies by Carole Ober and colleagues. In a 2016 New England Journal of Medicine article, further developed in a 2017 review in Current Opinion in Immunology (PMID: 28843541), Ober showed that children raised in traditional Amish farming environments exhibit dramatically lower rates of asthma and allergies, not because of their genetics, but because of their proximity to barns, animals, and microbial richness. Amish houses are full of what the modern world tries to eliminate: dust, dander, endotoxins. Early exposure to these allergens stimulates innate immunity because the exposures are mild, daily, and nonlethal. The immune system is not overwhelmed, it is trained.

This maps directly to what I described in my article Pain as a Teacher: the principle that adversity, in measured form, builds capacity, calibrates response, and teaches discernment. A student who has never been hit flinches at every feint. A child never scratched by the world develops allergies to life itself. Biological snowflakes.

We learn through discomfort and become more capable through experiencing it. A protected immune system, like an overparented child or a poorly trained fighter, becomes reactive, oversensitive, and prone to catastrophic overreach.

Frazer divided sympathetic magic into two laws: contagion (things that have been in contact remain connected), and similarity (like affects like). Both are at play in Ober’s study. Contagion: Amish children are constantly exposed to barn dust; particulate microbial DNA, animal hair, feed particles. Their bodies internalize the environment. Similarity: Their immune systems are challenged by irritants that resemble pathogens but do not overwhelm. Like trains like.

What is immune training if not the biochemical form of sympathetic magic? I use a similar logic in my classes when I provide demonstrations of bunkai and a staccato rhythm that punctuate demonstrations of ki-no-nagare. Expose the child to dust, and the body learns not to overreact to pollen. Strike the student gently, and he learns to defend against a real blow.

We laugh at the ancients for believing in healing relics and ritual bloodletting, yet it informed our modern immunology. We inject children with diluted toxins in a controlled modern ritual. We haven’t abandoned the logic. We’ve only changed the priesthood. This is not just a medical insight. It is a moral one. In every domain, education, parenting, politics, personal growth, we face the temptation to sanitize and protect. But the lesson from Ober’s research and from martial training is the same: overprotection breeds fragility. Controlled adversity breeds resilience.

Just as dust can inoculate, so too can pain, difficulty, and fear become allies in our moral and physical development. We do not conquer them by avoidance. We master them by exposure.

Ex malo bonum “From evil, good”[1]

_________________________________________

[1] Of course there is a footnote and a play on an old disagreement.

Seneca the Younger’s gave us the original dictum (from Epistulae Morales ad Lucilium 87.22) Bonum ex malo non fit, “Good does not come from evil.” His formulation is classic Stoicism; holding that virtue is self-contained and cannot arise from vice or wrongdoing. An evil man cannot do good acts. For the Stoics (which deeply informs my New England Pathology) the moral universe is a realm of intrinsic rational order, and any claim that good could arise from evil would imply that vice is somehow productive, which undermines virtue’s purity.

That reformed libertine, St. Augustine argued the opposite (in part no doubt to justify his own behavior). In his Sermon LXI (61) he offers a pointed and deliberate contradiction of Seneca’s conceptualization:

“Et hoc bonum est, ut ex malo surgat bonum. Non hoc dixit Seneca. Philosophus erat, et dixit: Bonum ex malo non fit. Et ecce fit: non ab homine, sed ab omnipotente artifice.”

(And it is a good that good arises from evil. Seneca did not say this. He was a philosopher, and he said: ‘No good comes from evil.’ But behold, it does: not by man, but by the omnipotent craftsman.)

St. Augustine’s argument is theological not philosophical. He needs to demonstrate the power of redemption. The cross as the ultimate evil turned to good. The crucifixion as salvation.

I must admit, my younger self rejected Augustine’s arguments as too apologetic, too philosophically weak – “God judged it better to bring good out of evil than to suffer no evil to exist” – really? The whole enterprise of The City of God was silly. Why allow the Fall only to provide for the greater glory of redemption? A righteous clockmaker would simply make it correctly the first time.

Yet watching humans be human, I can only conclude we gotta learn the hard way. So perhaps St. Augustine was on to something.

____________________

Update 10/20/25

A 2015 study published in the Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology concluded that there was “emerging evidence … regarding potential benefits of supporting early, rather than delayed, peanut introduction during the period of complementary food introduction in infants.” In short, early exposure to allergens was recommended.

These recommendations must have been broadly adopted because following the publication, and well reported by media outlets, were the results (this from the American Academy of Pediatrics): “We detected decreased rates of peanut or any IgE-FA in the period following the publication of early introduction guidelines and addendum guidelines. Our results are supportive of the intended effect of these landmark public health recommendations.”