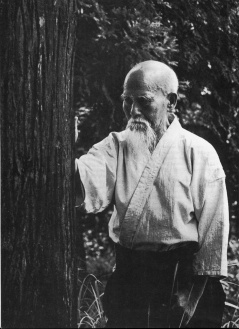

In our lineage, weapons training derives from Kazuo Chiba Sensei (February 5, 1940 – June 5, 2015) who learned the systematized forms from Morihiro Saito Sensei (March 31, 1928 – May 13, 2002) at Iwama (see below). The details of the connections are better kept as kadensho, but suffice to note that others have influenced the nuances of our weapons and I am catholic in my learning – always eager to steal from the best.

One of the most important concepts to learn in Aikido is that of ki-musubi (to tie spirits together). Ki-musubi is a wonderful gestalt term referencing the entirety of the encounter but perhaps too broad for my reductive methods of understanding.

So how does a reductive-pragmatist understand the concept? I look in part to those who lived by their skill. George Silver (ca. 1550 – 1620s) wrote a manual called Paradoxes of Defence wherein he discredits the rapier as an inferior weapon but more specifically references the use of “true times.” [1]

There are three specific “times” – the time of the hand, the time of the body and the time of the foot. It is worth taking the time to read and come to understand Silver’s concepts. As always it is far easier to convey in person and in class, but the principles are as follows: the hand moves more quickly than the torso which is again quicker than the foot. Think of the amount of mass each element must move and it should become obvious – the foot must move the entire body mass, the torso must move all the mass from the waist up, but the hand only need move the mass of the arm.

These lessons are still readily observed in modern fencing where the principle of a lineal thrust is still taught in the sequence of weapon, hand, body, foot. Watch any well executed lunge and notice that the tip is first extended to the target (acquisition) then the arm is extended (keeping the threat moving first and forward), then the torso leans in (giving added mass to the weapon), and then finally the front foot moves forward extending the entire body toward the target (adding momentum). While this sequence describes a lunge, the principles are the same for any action.

It is easy to see the intentions of an inexperienced practitioner because they typically move the feet first, telegraphic intent well before any threat is presented. As a simple example, focus on shomenuchi where uke delivers a descending overhead strike to nage’s head. If done in the time of the foot, uke will move the foot first thinking it necessary to plant the weight to then deliver a powerful stroke with the torso and arm through the weapon. The sequence is therefore, foot, body, hand. Nage will be able to easily enter with a straight thrust (time of the hand) because uke has telegraphed intention and not presented a convincing threat to nullify nage’s ability to respond. Silver calls this “false time” because uke has started the action with the wrong sequence, allowing nage to enter without fear. If this description isn’t clear – it will be easily shown in class.

A simple table – expanding Silver’s concept of “times”:

Weapon beats hand

Hand beats body

Body beats foot

When uke attacks in true time, the shomen strike starts from the kissaki – the sword tip is moved first (weapon), the hand/arm accelerates the sword (hand), the tanren is engaged (body), and finally the foot moves uke toward nage (foot). Because the weapon is presenting the threat and simultaneously guarding uke, nage must respond to the weapon in the same time – i.e., because uke has attacked in true time (hand first) nage cannot defeat uke simply by using a superior time.

Because there is no superior “time” that nage can employ, in Aikido we look to perfect the encounter with a unification of “times” – both uke and nage are responding in true time, equal sequences of movement, that then lead to the harmonization of movement, ki-musubi. This is most readily shown in the sixth kumi-tachi which is also known as otonashi-no-ken (the sword of no sound) or more commonly in our dojo simply as ki-musubi exercise. The importance of the exercise, once the basic kata (sequence of movement) is internalized, is to move beyond the rote pattern and to actually harmonize in time. And most importantly, the harmonization should not be the result of well scripted choreography but rather because of the binding of each other’s intentions – each discrete motion must be a targeted kill stroke that is then neutralized in concert then leading to the next sequential action.

Please understand that this exercise, I believe, represents Aikido’s ultimate goal – the beauty of the encounter (because there should always be an aesthetic element in an art) is the instantiation of silent and seamlessly integrated intentions.

Learning to be able to create that ideal encounter does require the polish from constant training, but also of what Silver would call “perfect understanding.”

Tempo

Tempo is not well explained in Aikido – ironically because of the focus on ki-musubi, or matched times. Because Aikido’s goal is that unified movement, most students never learn the tempo of combat. The concept of a beat and a half-beat are as critical in combat as is the feint to draw the opponent off time. In class, I demonstrate the concept of tempo and beats by moving away from a kihon presentation of technique by showing it as a bunkai (application) or with a different rhythm – breaking Aikido’s smooth lines into a staccato found in Karate and other arts. My intention is to expand the understanding of the movement patterns so that they are perceived as what they are – universal lines of motion. Most recently in class I demonstrated how ikkyo omote is the same when applied from shomen, or tsuki, or ai-hanmi katatedori. But I also demonstrated how ikkyo omote is the same movement as what a Karateka would know from one-step kumite as a chudan block followed by a chudan tsuki or what in sword and dagger play would be a sombrada followed by a dagger thrust. The lines of movement are universal, just played at different tempos and ranges. The single biggest problem in learning a martial art is understanding the art as a collection/compendium of techniques. This of course is fostered in the hierarchical nature of the testing requirements, each rank requires cumulatively more techniques to be mastered and demonstrated for proficiency. Perhaps there isn’t a better method to transmit the art, but I think it can lead to years of myopia (or, worse, anal glaucoma). We perceive the encounters as discrete techniques and rarely progress to the universal lines. Universal sounds grandiose, but I steal that term from Master at Arms James A. Keating (MAAJAK). “Universal” in his presentation is not to imply an arrogance of understanding, but to key us to the fact that given the limitations of the human body, there are a highly delimited number of ways that humans move. Every culture may put important flavors on the methods but given the way the human body is constructed we have universal limitations and therefore will all move through space and encounter each other on the same planes of action. It is an amazingly liberating and productive concept to re-frame the skills you have been learning and mastering for years. For me, I am trying to steal as much from his conceptualization of a universal framework and show the connective links – presentations from Karate or Kenpo for the staccato rhythms, sword and dagger for the integrated (wheeling) planes of engagement – to illustrate the concepts that may otherwise remain hidden in the art of Aikido.

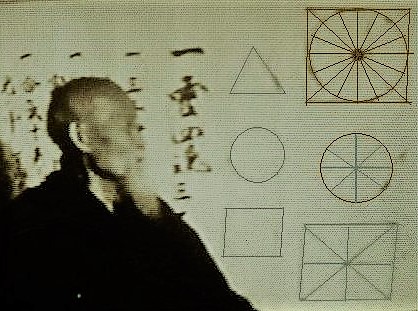

Returning to the basic 8 cuts

Recall that this diagram is illustrative of the eight universal planes showing lines of engagement from the viewer’s perspective on the vertical axis. This same diagram is also constantly on the horizontal axis. Specifically, at the center of the circle is nage’s body and its perimeter is described by one sweep of nage’s extended weapon (shikko).

The lines now represent angles of engagement – so, as an example the basic line of return for shomen uchi ikkyo would be (using the labeling of the diagram) uke attacks on line segment AE and nage returns on the line segment EA – both play the same line just different vectors. As a generalization, I submit for your consideration that all basic techniques (kihon waza) are played on the 180 degree line – irimi or ura – both are played 180 degrees in relation to the original line of attack. Think gyaku-hanmi tenkan, irimi entries: both place nage parallel to uke (180 degrees from nage’s original position).

Now the more advanced line of play tends to be 45 and then ultimately 90 degrees to uke’s initial line of engagement. I have demonstrated this from ai-hanmi katatedori ikkyo as a progression in arc of movement. So uke attacks on vector AE and nage returns on FB or ultimately on GC. The reason for the 90 degree angle as the more advanced is uke cannot “take ukeme” from that line (come to class if you don’t get what I mean here).

These diagrams can become increasingly esoteric in their presentation (almost becoming a fetish) but I remind you all of them to help visualize the universal planes of action and engagement, as a visual mnemonic or framework to help organize your techniques. And you have seen this before.

The perimeter therefore defines nage’s space of action defined within the time of the hand. Our ability to act and re-act is extended in space by changes in weapons (e.g., the empty hand is the shortest radius, then the leg, then a dagger, then a short sword, etc.) but typically extensions of action in space limit our ability to act in time.

____________________________________

[1] More on George Silver and the Paradoxes

____________________________________

If you haven’t already read this – Chiba sensei’s article on weapons training in Aikido is a seminal piece. I have re-posted it below to ensure it remains readily available:

The Position of Weapons Training In Aikido

A Consideration of the Unity of Body and Sword

Many people have asked me about the relationship between body arts and weapons training in Aikido. Most of those questions were influenced by the opinion (either positive or negative) towards weapons training by professional Aikido teachers, both those who positively incorporate weapons training in their Aikido practice and those who do not. These opposing practices inevitably create confusion among Aikido practitioners in general. I reluctantly acknowledge that the tendency to discuss right and wrong, or better or worse, stems from ideas about whether weapons training or body arts is the basis of Aikido practice.

I have responded to these questions one by one as they have been posed to me. However, I have begun to think that I have not been fulfilling my responsibility in presenting these fragmented responses. Therefore, I have decided to clearly describe my position and my beliefs on this issue. Let this be my comprehensive response to all those who have sincerely asked these questions in the past.

The questions that have been put to me fall into the following categories:

- Does Aikido base its training on body arts or weapons training?

- What is the importance of weapons training in Aikido?

- What was O-Sensei’s position and point of view on weapons training?

- Why, among the professional shihan from Hombu, do some train in weapons and some not?

Since these questions are closely related, I would like to first respond in a general way and then touch on the foundation of these issues, instead of responding to each individually.

First of all, let me state that I have not seen any historical or technical documents which clearly indicate that body arts in Aikido was based on weapons training, nor did I hear such an assertion from O-Sensei himself.

However, there are some passages from books I have read that slightly touch on this concept. One such passage can be found in the first Aikido-related book, published by Kowado in 1958. It is titled Aikido, and was written by Kisshomaru Ueshiba under the supervision of Morihei Ueshiba. In this book, Kisshomaru Ueshiba Sensei says: “All the movements in Aikido are exactly the sword movements. There are many areas [in Aikido] that can be understood easily by explaining sword concepts…”

A second passage in Aikido states that “. . . [Aikido] movements are based on the concept that the sword is an extension of the body. Therefore, if one holds a sword in one’s hand during [Aikido] movement, the movement becomes a clear case of sword-handling body movement, and therefore basically expresses the unification of body and sword . . .”

Further evidence comes from a book which is not a technical book on Aikido, but rather a memoir written by the former Sumo wrestler Tenryu, who challenged O-Sensei and was defeated by him. In the memoir, Tenryu recalls, “I was at the pinnacle of my career. I had nothing to fear in those days. Now that I think about it, I was quite conceited, until I encountered an incident that made me understand the depth and fearsomeness of real Japanese martial arts. This brought me down from my conceited state.”

After describing his state of mind before he challenged O-Sensei, Tenryu further describes O-Sensei’s Aikijutsu: “… this [Aikijutsu] is the ultimate martial art, which embodies the concept of swordwork in body movement.”

Unfortunately, I do not have a copy of Tenryu’s memoir with me as I write this, so I cannot quote him word for word, but the above is essentially what he recalls.

I recognize that the examples presented above do not clearly and systematically describe the unification of body and sword in Aikido. In the context in which they are placed, they are not conclusions drawn from systematically structured technical evidence, but rather they are statements based on an individual’s experience, feelings or impressions. Strictly speaking, they lack the logical grounds to withstand technical and historical criticism. We need to wait for further research.

However, to speak frankly, arguing about which came first, body or weapons training, is like asking which came first, the chicken or the egg. It does not contribute positively or constructively toward our practical training.

I am a practical person. I base my decisions on actual situations. It seems clear to me, based on facts derived from my own years of training, that at its very root, Aikido expresses the unification of body arts and weapons training, both philosophically and physically. This is an empirical truth. Thus, as it is, it does not require historical documentation or evidence. At the same time, as a practitioner viewing the whole issue from a practical point of view, I can state that professional Aikido teachers – those who practice with weapons and those who don’t practice with weapons – express inevitable and necessary aspects of the continuing development of Aikido.

On one hand, if you stand by the premise that Aikido is a martial art in which body arts is the ultimate completion and the end stage of weapons training, you may logically conclude that body arts is therefore the ultimate form of martial arts. Thus, the interpretations of those teachers who pay most of their attention to body arts certainly make the most common sense.

On the other hand, as I will attest from my own experience, if you stand by the premise that Aikido fundamentally presents a unification of body and weapons work, the study of weapons as an expansion of body training becomes a natural and necessary step in the development of Aikido. These positions need not be compared as to which is more legitimate, or which is better. Both should be accepted as inevitable and necessary aspects of the development of Aikido.

Whether a practitioner holds to one or another of these two positions is not necessarily the result of reason or logical thought. It has more to do with an individual’s human tendencies or sensitivities. There is an undeniable force working deep inside our consciousness. One might even call it destiny. It is similar in nature to the working of that force which leads to another most fateful encounter – that between a man and a woman. We interact with many people, but we finally end up with one spouse.

As far as my 40 years of Aikido life is concerned, I must say that my first encounter with O-Sensei and my lifetime association with Aikido can only be described as being of the same kind of encounter with destiny as that between husband and wife. My progression toward expanding Aikido body arts into weapons training is akin to the expansion of the same fateful encounter.

In order to more fully explain this progression, I must describe an incident that occurred in the early days of my training as a martial artist. I was studying Judo. I thought I was progressing fairly well in my Judo training. However, in 1956 I was challenged by a Kendo practitioner to a duel. We fought in a field. I was completely defeated, beaten all over my body. I could not do a thing, despite my Judo skills. With all my knowledge of Judo, I had no defense against a sword.

I realized then that no matter how much I trained and how far I progressed in Judo, I would never be able to fight against a sword. I also recognized that, in the same situation, a Kendoka without a sword would be no match for a Judoka, given Judo’s unique ability to deal with an empty-handed condition. This incident filled me with despair and confusion, and led me into a very dark time.

I decided that I had to abandon my Judo training, which I had thought would be my lifelong path. It seemed quite clear that Judo and Kendo represented completely different dimensions, and that under their own rules and conditions it would be impossible to fight in the same arena. Judo is excellent in hand-to-hand combat and Kendo is excellent for cutting and lunging with a sword from longer distances (ma-ai), but neither of them contains both characteristics. I was looking for an ultimate martial art that contained both elements.

In my profound anguish and confusion, while I was still unable to find my future direction, I was like a thirsty man looking for a drop of water in the desert. I wandered about the streets of Tokyo, looking for something that might not even exist. Then, in a bookstore, I found the book mentioned earlier written by Kisshomaru Ueshiba. There was a small photo of O-Sensei on the back of the front page. When I saw it, I instinctively knew: This was the man I was looking for to be my lifetime master. I made my decision then and there: No matter what it took, I was going to be his disciple. It was the moment of my destiny.

However, since I had absolutely no knowledge of Aikido, the book did not make any sense to me no matter how many times I reread it. Given my knowledge of martial arts at that time, Aikido was beyond my comprehension. The only passage in the book that gave me slight hope was the passage I cited above, regarding the relationship between body and sword. The passage was a short one; however, instinctively I was able to perceive the possibility that Aikido contained the answer to my despair. I decided right then that Aikido was the art I was looking for, the one to which I would devote the rest of my life. My direction in life was clear.

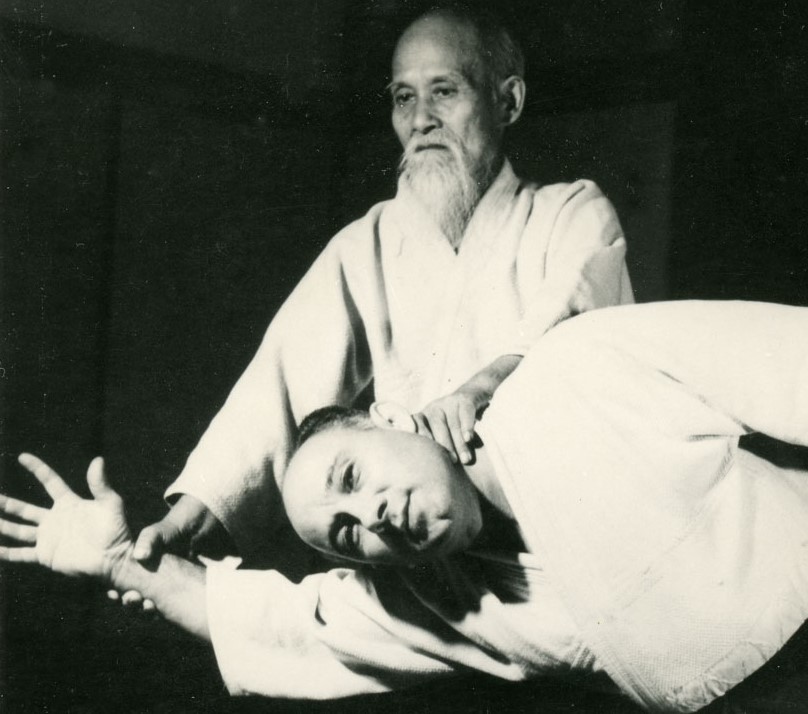

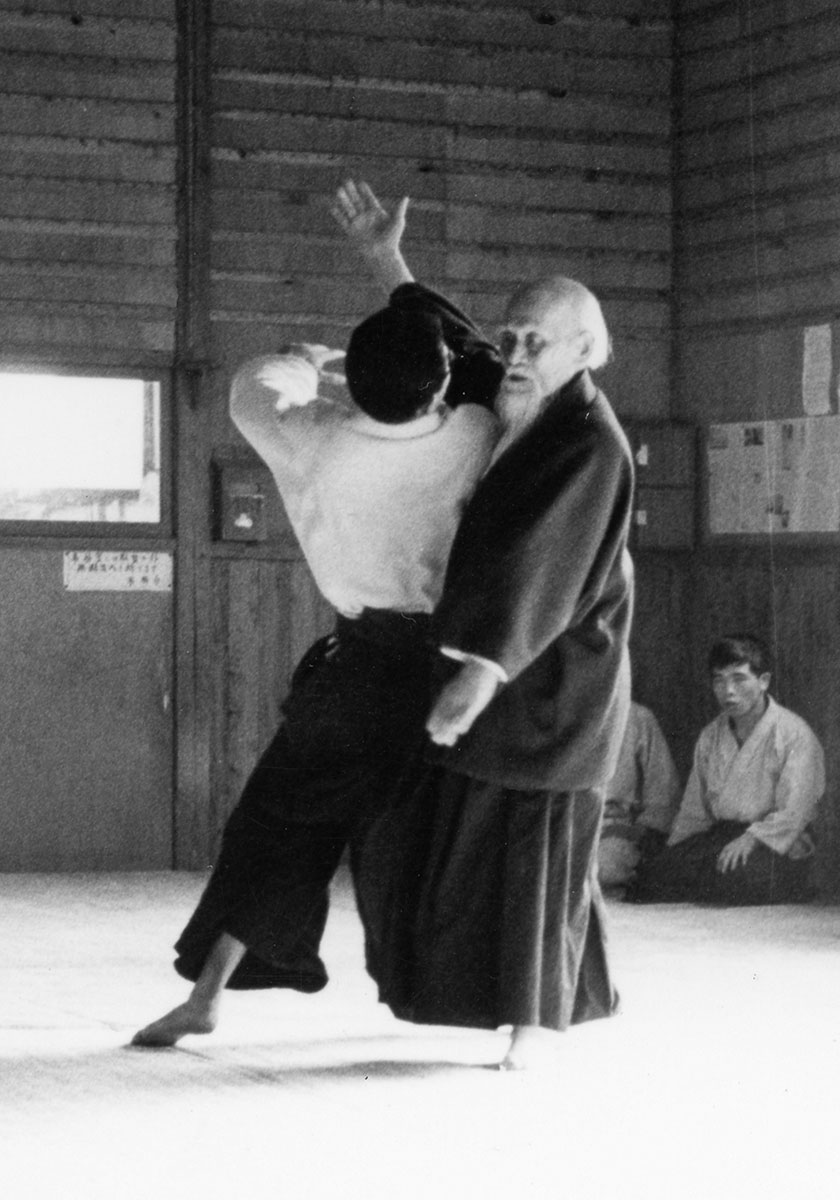

As far as I remember, O-Sensei never talked about the relationship between body arts and weapons training. However, I had no doubt in my mind by observing his daily life that he embodied, and clearly showed, the unification of body and sword, both in his very presence and in his Aikido. As far as my own experience of it is concerned, O-Sensei’s instruction in weapons training had no obvious structure. It was always natural and self-contained, flowing from him freely.

One of the very important characteristics of O-Sensei that I recall, which has not been paid much attention to, was that O-Sensei himself, while certainly a path seeker and practitioner, was never a teacher in the present-day definition of instructor or teacher. He manifested his own inexhaustible spirit toward seeking a deep Way, and that was the only method he used to guide us. He never looked back at his followers. He was always out there freely communing with the gods. In his attitude, in his daily life and in his high devotion to the gods, he showed us the Way. He paid no attention to mundane affairs.

Time after time O-Sensei told us, “If you progress 50 steps, I will be ahead of you 100 steps.” These seemingly conceited words galvanized us, energized us to follow him. But more importantly, in his mind it was really true. His spirit was in such a high place that he freely communicated with gods in his daily life. His attitude and the way he carried on his life appeared to me to manifest an extraordinary, almost supernatural beauty. There was no need for interaction to be based on ordinary language used in daily life.

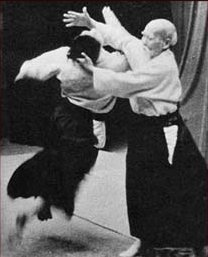

As far as actual techniques of weapons training were concerned, he taught me only two methods. One was yokogi uchi, where you place a bundle of live branches horizontally on a stand and strike it with a bokken. The other was spear-thrusting training, where we thrust a jo into a Kendo torso-protector wrapped around a large pine tree. Even at that, it was not really instruction, as we speak of instruction in the normal sense. He demonstrated attacking these targets with all his might, and we just tried to copy his moves.

Saito Shihan, after many years of effort and research at Iwama, organized a weapons training system: Ichi no tachi through to go no Tachi and kimusubi no tachi, which was the basis for Sho Chiku Bai swordwork. Through necessity, out of a sense of responsibility as O-Sensei’s uke, and because I traveled with him in my early days of training, I learned these forms independently from Saito Shihan.

Before my time (i.e., before 1960), Tamura Shihan and Nishiuchi Shihan were O-Sensei’s ukes for weapons. I tried very hard to steal their handling of weapons and trained by myself. It was vital, and my primary responsibility as O-Sensei’s uke, to not make blunders. At that time I was merely a shodan, with only a year and a half of Aikido training. This tortured me psychologically to no end. I struggled all alone in those days. None of my sempai at Hombu offered to teach me weapons work.

My strongest fear was that I might dishonor O-Sensei’s fame because of my lack of proper weapons skills. I did not want people to look at O-Sensei, who was then a highly regarded martial artist – one in a million, established in an indisputable position as such – and say, “He might be a great master, but look at his student. Is that all he has?”

Also, as an attacker, I did not want a situation to arise where O-Sensei could not show all his capabilities because of my lack of skill. My trips with O-Sensei to seminars around Japan might last four or five days or up to five weeks. What I recall fondly today is how many nights I lay sleepless, recalling how I had seen O-Sensei move that day and thinking about my seemingly impossible task, which was to understand his movements in order to improve my attacks, so that O-Sensei’s fame would be kept intact.

As I think about it now, what I see most clearly is the deep affection that O-Sensei showed me by putting me in this situation. He gave me no choice: He made me face an impossible task. By doing so, he taught me a lesson: to accept my natural level of skill as it was, and to recognize that the fundamental concept of a martial artist (Budoka) is that one must be ready to accept any circumstance with one’s whole self, leaving regret behind. Through his action O-Sensei taught me the fundamental attitude of a martial artist.

The major difference in teaching methods between the martial arts and the contemporary education system is that in martial arts, the teacher throws students into a seemingly impossible situation. There they must struggle by themselves, and search for a fundamental truth by themselves, given their capacities and abilities. There is no verbal instruction, no discussion of detail. This is a unique method of training within traditional Japanese culture. It is a completely different world from the present-day education system, including contemporary martial arts.

I do not feel any contradiction in acknowledging the fact that my weapons training method differs from that of O-Sensei. What I am or what I do today is based on the “cause,” in the Mahayanist Buddhist sense of “cause and effect.” There is a “cause” that makes me who I am today and that is based on the accumulation of my life experiences and on the manifestation of my personal development. At this point in my life, I have been seriously seeking the Way for over half a century. Everything I have and everything I am, including the entire creative and latent potential of my Aikido life, exists at this point in my life.

There are two elements I would like to emphasize in discussing the practical effects of training with weapons in Aikido practice.

The first element is that of the ideal body constitution. This is the “Aikido body” that I always talk about, and its realization in one’s body through the stages of Aikido training. This body constitution can be more easily observed through the handling of weapons rather than through observing body work, especially in basic weapons maneuvers, such as suburi and basic jo exercises. There may be many reasons for this.

One important factor is that in the case of body arts, the observer often pays more attention the relative effect (impact) created by the execution of technique, and to the dynamic and flowing movement realized between the practitioner (tori or nage) and the receiver (uke). (If we analyze the movement in terms of cause and effect, where the practitioner is seen as the “cause,” and the relative outcome that appears to be the result of the execution of the technique is seen as the “effect,” often the observer can only see the “effect” and not the “cause.”) In focusing attention on impact or on fluidity of movement, the observer often fails to observe the body constitution and its use by tori.

In contrast, the body constitution and the qualities of use (unification of body, harmony, centeredness, totality, etc.) of the tori can be clearly seen by his or her handling of the jo or bokken. It is unfortunately the case that in the practice of body arts that the movements of uke can often contain certain elements of artifice. However, in the basic handling of weapons, there is no room for conscious elaboration or showmanship in body movement. Tori must expose the entire naked self, a totally independent body, to an observer.

The most important aspect of Aikido is its unique ability to enable practitioners (tori) to see their own body constitution (which is the personification of the state of mind) as it manifests on the receiver of the technique (uke), through the relationship between practitioner and receiver. A practitioner sees in the mirror of uke’s body movement the presence of his mind and his fundamental characteristics. Because of this unique ability, Aikido emphasizes the development of the spiritual foundation in practitioners. Therefore, it is vitally important for Aikidoists to be able to observe their body constitution, and to see the way it works.

The second element I would like to emphasize is the relationship between Aikido training and age. As biological beings, we face the inevitable challenge of aging and its acceleration and imposition of many physical constrictions. Many of us are reaching an age where we must balance the ailments of our bodies and our Aikido training in order to extend our training lives. It has been almost half a century since Aikido was introduced to Europe and the U.S., and the pioneers who contributed to the initial stage of its introduction are between 50 and 80 years old. It is very sad to see these people, whom I consider my training mates and comrades, dropping out of Aikido. It is a great loss to the Aikido community if we lose the accumulated experience and knowledge of these people.

What can we do? What can we prescribe to remedy this situation? We can certainly tell young people, who are the art’s future and its potential, that it is vitally important for them to condition and strengthen their bodies so that they will be able to extend their training lives.

However, this advice cannot apply to all practitioners. As we all know, because of the philosophy and nature of Aikido, it tends to attract a relatively older generation of people. There are many cases where beginning students have already passed the age when basic body conditioning should have taken place. We can of course discuss the importance of nutrition and recommend body conditioning according to age, or to introduce yoga. However, generally speaking, we must leave this up to the individual’s judgment and selection.

It is very important to practice ukemi in Aikido training. However, the damage to the body from the accumulated impact of ukemi practice, when it is done in excess, cannot be disregarded. Therefore it is very important to master ukemi as an independent art. This is a pressing issue for older students. Suwariwaza training, which is such important basic training in Aikido, is also very difficult for members of older generations. Especially in Western culture, where the predominant habit is to sit in chairs, the weakness of the lower body is more manifest in older people. Suwariwaza is thus more difficult for them.

I think that weapons training can potentially overcome the tendency to fail to observe our body constitution, and to remedy the difficulties experienced by older students. In basic weapons training the techniques are done standing, there is little or no ukemi and there exists sufficient ma-ai (distance) so that the degree of influence of power or weight which one sees manifest in body arts is limited. (The degree of influence of power and weight changes in relation to distance, or ma-ai.) Thus weapons training – using weapons as an extension of the body – allows students to study and train in the principles of Aikido relatively free of age differentials. One of the reasons that there are more old Kendoka still actively training, in contrast to the number of older Judoka, is that working with weapons frees the body from some of the more severe constraints imposed by aging.

The position of weapons training in Aikido should be reviewed in terms of these conditions.

Ultimately, I am convinced that the fundamental principle of Aikido is found in muto no kurai – the state of “non-sword” or being unarmed in a superficial sense. The principle goes beyond being armed or unarmed, which are relative terms. At this stage, however, suffice it to say that it does not negate our weapons training. The technical and philosophical understanding of muto no kurai is a basic and important element of my life’s work.

It has not been an easy road. But Aikido so far has not betrayed my expectations. Nevertheless, the highly polished techniques, unified with the profound philosophical principles at the foundation of this art, have made my quest incredibly difficult. I have been in deep despair many times because no matter how much I trained, or how far I traveled along the path, I have been unable to grasp its totality. But at the same time, a glimpse of something noble that I catch from time to time through my daily training makes me feel that I am alive and encourages me to continue on this path.

Aikido is a noble art. Because of its nobility, it is very fragile and easily damaged. But because of its very fragility, Aikido has never ceased to be precious to me.

Author’s notes:

1. To support the position expressed in this article, I would like to mention the relationship between Aikido and Iai Batto Ho training. It is important, while training with bokken, to understand the concept of cutting, since an actual sword cuts when it is properly handled. This sense of cutting is difficult to attain solely by bokken training. Iai Batto Ho allows a student to understand correct sword-handling methods. Also, the person who introduced me to the path of Iai Batto Ho was O-Sensei himself.

2. I would also like to state that though it may appear that I criticize Judo and Kendo in this article, I have no intention of doing so. The evaluation of these arts as expressed was a conclusion derived by a 16-year-old boy who had a serious experience and an impression. Through this experience, I met my lifelong master, Morihei Ueshiba, and my path was clarified. There was no criticism intended. I know exactly what real Judo and Kendo are like, and I wrote this essay with full respect for those arts.