Liberty In Our Time – YouTube channel on libertarian authors

A History of Money and Banking in The United States

The American Economy and the End of Laissez-Faire (1870 to WW2), lectures delivered by Murray Rothbard

Liberty In Our Time – YouTube channel on libertarian authors

A History of Money and Banking in The United States

The American Economy and the End of Laissez-Faire (1870 to WW2), lectures delivered by Murray Rothbard

BY EMMA BETUEL AUGUST 5, 2021 (Atlas Obscura)

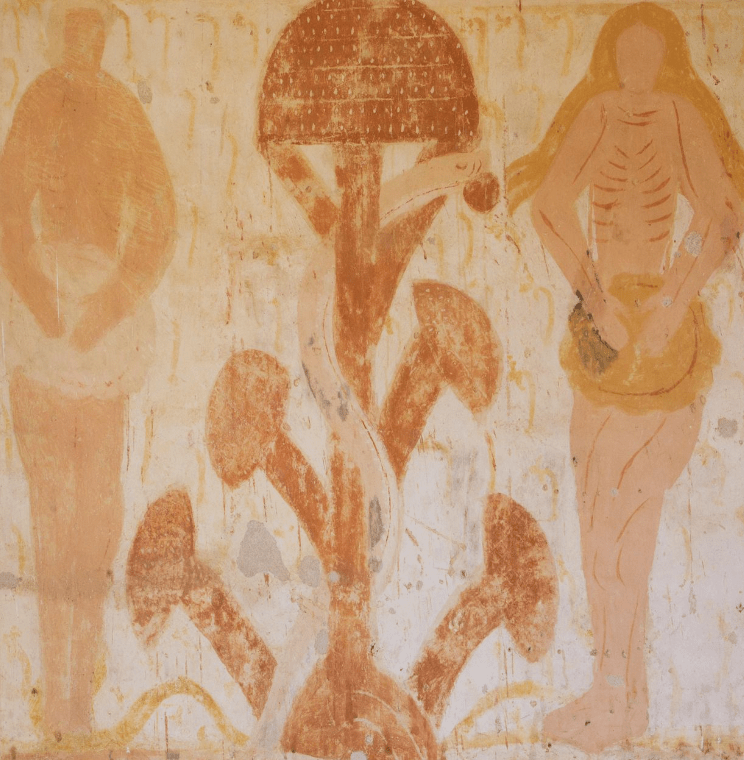

Does This Medieval Fresco Show A Hallucinogenic Mushroom in the Garden of Eden?

In France, Plaincourault Chapel features a peculiar depiction of the Garden of Eden’s Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil.

ADAM AND EVE STAND IN the Garden of Eden, both of them faceless. Eve’s ribs are bold slash marks, as if the artist wanted her to appear almost skeletal. But that is not the strangest thing about this faded 13th-century fresco inside France’s medieval Plaincourault Chapel. Between Adam and Eve stands a large red tree, crowned with a dotted, umbrella-like cap. The tree’s branches end in smaller caps, each with their own pattern of tiny white spots.

It’s this tree that has attracted visitors from around the world to the sleepy village of Mérigny, some 200 miles south of Paris. Tourists, scholars, and influencers come to see the tree that, according to some enthusiasts, depicts the hallucinogenic mushroom Amanita muscaria. Not everyone agrees, however, and controversy over the fresco has polarized researchers, helped ruin at least one career, and inspired an idea—unproven but wildly popular, in some circles—that early Christians used hallucinogenic mushrooms.

The question of what was painted on the back wall of Plaincourault goes back at least to 1911, when a member of the French Mycological Society suggested the thing sprouting between Adam and Eve was a “bizarre” and “arborescent” mushroom. The idea that the Tree of Life was actually A. muscaria pops up in the 1925 book The Romance of the Fungus World, which presents a “curious myth” about the Plaincourault fresco depicting the hallucinogenic mushroom, though there is no suggestion of its use by early Christians.

A quarter-century later, the earlier mentions lured R. Gordon Wasson to see the fresco for himself. Wasson was a PR exec in banking, and also an amateur mycologist. Although he had no formal training in the field, he’s known today for his prolific writing on mushrooms, particularly of the hallucinogenic variety, and fungi-focused travels, some of which were secretly funded by the CIA, which had its own interests in the topic. In 1952, when Wasson saw Plaincourault for himself, he wasn’t convinced, and sought the opinion of Princeton art historian Erwin Panofsky. The scholar was blunt. “The plant in this fresco has nothing whatever to do with mushrooms,” Panofsky wrote.

The idea persisted, however, and was loudly revived in 1970 by John Marco Allegro, a scholar of ancient languages at the University of Manchester. In his book The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross, Allegro argued that Christianity itself had derived from a fertility cult whose members ingested hallucinogens. He called the Garden of Eden story “mushroom-based mythology.” His visual evidence was the fresco at Plaincourault, in which “Amanita muscaria is gloriously portrayed,” he wrote. Allegro was already a controversial figure: He had been publicly criticized by colleagues on a team translating the Dead Sea Scrolls for his overly imaginative interpretations. But The Sacred Mushroom was the final nail in the coffin of Allegro’s career.

Speaking to Time Magazine, one scholar called the book “a Semitic philologist’s erotic nightmare.” Other critics included Wasson, who wrote, “One could expect mycologists, in their isolation, to make this blunder. Mr. Allegro is not a mycologist but, if anything, a cultural historian.” Despite the broad and negative reaction to the book, Allegro’s interpretation of the Plaincourault fresco lives on, attracting new believers.

Two of the fresco’s current champions are Julie and Jerry Brown, neither of whom are mycologists or art historians. Jerry is an anthropologist at Florida International University, where he teaches a course on psychedelics and culture. Julie is an integrative psychotherapist. The Browns believe that Allegro got a few things right, namely, the idea that early Christianity could have incorporated the use of psychoactive plants, and that mushrooms depicted in Christian art are proof of that use. Jerry Brown calls the fresco at Plaincourault “seminal” to this argument.

“If Allegro were right, and Plaincourault did represent a stunning example of a psychoactive mushroom in a late 13th-century fresco, then entheogens [psychoactive substances] could be seen as integral to the origins of Judeo-Christianity with a usage persisting at least into medieval times as evidenced by this fresco,” says Brown.

While many religions past and present incorporate some form of psychoactive plant, “as yet, there is no convincing biomolecular archaeological evidence of the use of hallucinogens by early Christians,” says Patrick McGovern, the scientific director of the Biomolecular Archaeology Project at the University of Pennsylvania.

Art historians are also skeptical that the medieval fresco is secretly showcasing Christianity’s psychedelic roots. “I can assure you that the arboreal form at Plaincourault, or elsewhere for that matter, in no way references a particular species of mushroom,” says Marcia Kupfer, an independent scholar of medieval art and author of Romanesque Wall Painting in Central France.

Elina Gertsman, an art historian at Case Western Reserve University, says she’s not one to shy away from well-placed speculation, but even she can’t get behind the idea that the tree is a hallucinogenic mushroom. Instead, she says, medieval artists may have been experimenting with new ways to stylize trees. There are countless examples of medieval images where artists did this, including lions that appear to be wearing glasses, or elephants with mitten-like feet. “I think you will be hard-pressed to find a specialist in medieval art who disagrees with me and subscribes, instead, to the psychedelic Christianity idea,” Gertsman says.

Jerry Brown has heard the art historians’ assessments and remains unswayed. “As Louis Pasteur said, chance favors the prepared mind,” says Brown. “My mind, having taught psychedelics for decades, recognized it.”

There is no shortage of prepared minds out there: The idea that the Plaincourault fresco depicts A. muscaria as the Tree of Life thrives on social media posts, blogs, and in digital image collections. Some of the sites alter the image of the tree to enhance its resemblance to the mushroom, boosting the red color or employing other “pretty blatant manipulation,” says Gertsman.

The idea of Plaincourault depicting a mushroom tree got another boost recently from comedian Joe Rogan, whose podcast, The Joe Rogan Experience, was the top podcast on Spotify in 2020. “That is an original fresco from France, 13th-century fresco depicting Adam and Eve and the Tree of Knowledge,” Rogan told his millions of listeners. “That mushroom is a mushroom called the Amanita muscaria.”

If the idea of the Plaincourault fresco depicting a hallucinogenic mushroom has been debunked, repeatedly, by scholars in the best position to interpret it, why does it persist? The reason may be a combination of shifting societal attitudes and the very human tendency to see what we want to see.

Americans, for example, are becoming more open to the idea of psychedelics, says Ido Hartogsohn, the author of American Trip: Set, Setting and the Psychedelic Experience in the 20th Century. In 2017, 53 percent of a nationally representative sample of 1,145 Americans said they supported medical research into psychedelics. In 2020, Oregon decriminalized psilocybin, a hallucinogenic compound found in several types of mushroom, and legalized it in therapeutic contexts—the first state to do so.

A growing acceptance of hallucinogens in the mainstream now may make many of us more willing to believe that they were used in the past, even in cultures and periods where hard evidence is lacking. “In some cases, advocacy of psychedelics can lead some to find clues for their existence everywhere, even when the supporting evidence is quite speculative in nature,” say Hartogsohn.

For the last 100 years, people have been seeing mushrooms when they look into the image at Plaincourault. Today, it may be easier than ever to see them, even if they’re not really there.

____________________________________

Khan Noonien Singh is my favorite Star Trek character. In Space Seed (1967), Ricardo Montalbán plays Singh the genetically engineered despot known as the last tyrant from the Eugenic Wars::

KIRK: Name, Khan, as we know him today. (Spock changes the picture) Name, Khan Noonien Singh.

The full script

SPOCK: From 1992 through 1996, absolute ruler of more than a quarter of your world. From Asia through the Middle East.

MCCOY: The last of the tyrants to be overthrown.

SCOTT: I must confess, gentlemen. I’ve always held a sneaking admiration for this one.

KIRK: He was the best of the tyrants and the most dangerous. They were supermen, in a sense. Stronger, braver, certainly more ambitious, more daring.

SPOCK: Gentlemen, this romanticism about a ruthless dictator is

KIRK: Mister Spock, we humans have a streak of barbarism in us. Appalling, but there, nevertheless.

SCOTT: There were no massacres under his rule.

SPOCK: And as little freedom.

MCCOY: No wars until he was attacked.

SPOCK: Gentlemen.

KIRK: Mister Spock, you misunderstand us. We can be against him and admire him all at the same time.

SPOCK: Illogical.

KIRK: Totally.

In under two minutes, the episode distills humanity’s oldest paradox: our irrational admiration for strength, even when it enslaves us. Trump, Putin, Xi the modern strong-men, trade on that same primitive attraction, promising national order and renewal. (Small-minded religious zealotry fuels the Taliban, Khamenei, etc., who hold power because of a similar slave-mentality of the populous.[1])

KIRK: Forgive my curiosity, Mister Khan, but my officers are anxious to know more about your extraordinary journey.

SPOCK: And how you managed to keep it out of the history books.

KHAN: Adventure, Captain. Adventure. There was little else left on Earth.

SPOCK: There was the war to end tyranny. Many considered that a noble effort.

KHAN: Tyranny, sir? Or an attempt to unify humanity?

SPOCK: Unify, sir? Like a team of animals under one whip?

KHAN: I know something of those years. Remember, it was a time of great dreams, of great aspiration.

SPOCK: Under dozens of petty dictatorships.

KHAN: One man would have ruled eventually. As Rome under Caesar. Think of its accomplishments.

SPOCK: Then your sympathies were with

KHAN: You are an excellent tactician, Captain. You let your second in command attack while you sit and watch for weakness.

KIRK: You have a tendency to express ideas in military terms, Mister Khan. This is a social occasion.

KHAN: It has been said that social occasions are only warfare concealed. Many prefer it more honest, more open.

KIRK: You fled. Why? Were you afraid?

KHAN: I’ve never been afraid.

KIRK: But you left at the very time mankind needed courage.

KHAN: We offered the world order!

Kirk has trapped Khan drawing out his confession. Yet the deeper irony is that the very existence of Starfleet implies that humanity is in fact unified, as Rome under Caesar, capable of amazing accomplishments such as an inter-stellar Federation.[2]

Khan’s claim that he left Earth for “adventure” is disingenuous; he and his supermen were overthrown and they fled. In Star Trek canon, the Eugenic Wars lasted only four years so Khan’s rule was contentious at its start and did not last. For all his genetic superiority, Khan was far less successful than Xi.

The themes tackled by shows in the 1960s provide a robust analysis of the human condition. Both Star Trek (1961-1969) and The Twilight Zone (1959-1964) continue to reward the careful watcher. Yet for all their insight, the conclusions were steeped in post-war American optimism.

The idea that Khan’s tyranny was overthrown so easily feels naïve, implying that people naturally reject order. If the order Khan provided was truly benevolent, rebellion would be unlikely. Clearly it takes severe oppression of life and liberty before people revolt. The Arab Spring (2010-2011) blew over with no real change. And while I would love to see the current (2022) protests in Iran and China cause political change, I am not optimistic.[3]

Along with the unrealistic optimism that Khan’s tyranny was overthrown, is that Kirk defeated him. Selective breeding for the betterment of the race doesn’t ensure success.

KIRK: Well, they were hardly supermen. They were aggressive, arrogant. They began to battle among themselves.

SPOCK: Because the scientists overlooked one fact. Superior ability breeds superior ambition.

KIRK: Interesting, if true.

Eugenics holds the promise of perfection, but the writers in the 1960s were often the same men who fought Hitler and knew first-hand the horrors of a master-race inspired vision. The hubris of Nazi Germany was undone not by supermen but by ordinary soldiers: an echo of Copland’s Fanfare for the Common Man.

Although the global population has crested eight billion, the declining birth rate (in the West) is a much bigger risk to civilization than global warming, according to Elon Musk. Musk and other tech elites believe they represent the solution to declining birth rates by ensuring humanity’s survival through interplanetary expansion. This is Musk’s motivation to colonize Mars – so that mankind isn’t a mono-planetary species.

Genomic Prediction – Life View

Superior ability leading to superior ambition: to believe that you have the answers and are the solution.

It’s a proposition uniquely suited to Silicon Valley’s brand of hubris: If humanity is on the brink, and they alone can save us, then they owe it to society to replicate themselves as many times as possible

It is hard to argue with Musk’s tweet about the movie Idiocracy, in which the intelligent elite stop procreating, allowing the unintelligent to populate the earth.

Been around the world

Harvey Danger Flagpole Sitter (made more famous by Green Day)

And found that only stupid people are breeding

Cretans cloning and feeding

It does feel that way.

It is easy to criticize the idea that demography as destiny because those countries with higher birth rates are generally less economically developed. Thus a policy which would encourage higher birth rates among the successful will quickly bleed, erroneously, to eugenic theories (qv. Taleb vs Murray). There is an irony that in the modern economy, the successful, typically, have far fewer children precisely because they have been successful and therefore have fewer evolutionary challenges constraining their ability to reproduce. Modern technology has removed traditional limitations and economic incentives are such that it is “better” to shower resources on fewer children so they can compete successfully.

Musk (and others) frame pro-natalism as moral duty: to reproduce excellence for the species’ sake. (To be fair, Musk would more likely embrace tech-enhancement over genetic refinement.) Reportedly, his goal isn’t domination of the species but rather its assured continuation. Should humanity’s population grow to its interplanetary carrying capacity? If so, should it be comprised of those who have the highest potential?

Script writers resist that narrative of planned perfection. Consider Gattaca (1997), The Accountant (2016) – with autism leading to higher performance, and Oliver Sacks reported that Tourette’s can lead to hyper-accurate surgeons. In short Darwinian mechanisms could select for non-optimal (by current measures) genetics. Evolution prizes adaptability, not design. Are we seeking perfection or survival? There is a distinctly American optimism that acts as an antidote to elitism: perfection is the enemy of the good.

Space Seed concludes with Kirk exiling Khan and his followers in the Ceti Alpha star system on a planet that is “habitable, although a bit savage, somewhat inhospitable” according to Spock, but one which Kirk remarks is “no more than Australia’s Botany Bay colony was at the beginning.” The closing lines were originally intended to be optimistic:

SPOCK: It would be interesting, Captain, to return to that world in a hundred years and to learn what crop has sprung from the seed you planted today.

KIRK: Yes, Mister Spock, it would indeed.

But the optimism of 1967’s episode proved too cheery for 1982‘s darker sequel.[4]

____________________________

[1] The American moral police, fortunately, are failing to establish a majority despite the Dobbs Decision. Fortunately, women’s rights (and the general spirit of Liberty) are ingrained sufficiently to bolster the legal system’s protections. Let us hope that each state actually enacts formal legislation. More tellingly, the US Supreme Court has never overturned Buck v. Bell (1927) that allows forced sterilization…an uncomfortable reminder that eugenic thinking was not confined to fiction or the Axis powers.

[2] In the original series, the unification of Earth isn’t well addressed and the inter-stellar relationships forming the United Federation of Planets are a multicultural democracy. Gene Roddenberry was an unrepentant optimist who believed in humanity:

We are an incredible species. We’re still just a child creature, we’re still being nasty to each other. And all children go through those phases. We’re growing up, we’re moving into adolescence now. When we grow up – man, we’re going to be something!

Gene Roddenberry

This optimism was not naïve; it was deliberate humanism. Roddenberry imagined the Federation as an aspirational Caesarism, empire sublimated into cooperation, reflecting America’s postwar belief that progress could redeem power.

[3] As long as tyrannical regimes retain military loyalty, mass protest rarely translates into regime change. The West is fortunate that self-determination and weapon ownership have deep cultural and legal foundations. An armed citizenry, whatever its costs, complicates the consolidation of tyranny. (cf. Is There a Relationship between Guns and Freedom? Comparative Results from 59 Nations, Kopel, D. et alia, Texas Review of Law and Politics, Vol. 13 (2008)). The data can be parsed, of course, and The Atlantic has an intelligent review that concludes with a lower confidence on the relationship, but I believe Casey Michel critique underestimates the historical coupling of civic freedom and martial competence.

Dr. Pippa Malmgren asks the cogent questions and shows tyrannies fear their populous – hence zero-Covid policies and Great Firewalls. She concludes that the breakup of these “autarkies” is possible: “What is the probability that both, or either, Russia and China actually break up into smaller pieces as people fight against being locked up in virtual digital prisons, in the prison of involuntary conscription or in the home in lock-down, which has become the new prison?” She is far more optimistic than I am.

“We want food, not Covid tests, We want reform, not Cultural Revolution. We want freedom, not lockdowns. We want votes, not a ruler. We want dignity, not lies. We are citizens, not slaves: Remove the despotic traitor Xi Jinping!”

Let us hope the Chinese people prevail!

Update 12/4/22 – Iran signals the abolishing of its moral police in response to the continued protests. Hmmm…. I remain skeptical.

Update 12/5/22 – Alas, skepticism justified…

[4] The Wrath of Khan released in 1982 when tensions between the United States, Russia and China were no better than they are today. The difference then was that Russia was perceived as the greater threat but China’s ambitions for Taiwan were only just starting to be thwarted. US – Soviet relations had deteriorated and the START negotiations were largely at impasse (summary).