The myth begins with Zeus in disguise. He comes to Leda, queen of Sparta, in the form of a swan. Later poets make it salacious. The earlier versions make it necessity.

Their union yields eggs.

From them Castor and Polydeuces emerge, and in many traditions Helen and Clytemnestra as well. Only the brothers are called twins, but that is a simplification. They are of different fathers.

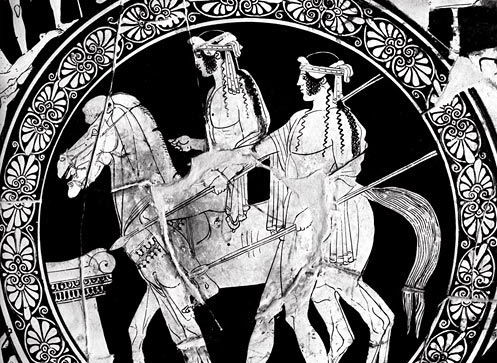

Castor, son of Tyndareus, belongs entirely to the human realm: he learns horses, reins, balance, the arts of mastery that require time and discipline. For Polydeuces, son of Zeus, excellence is an unearned birthright: strength that does not diminish, a body that will not succumb to death.

Helen, meanwhile, is not divided at all. She is excess without counterpart, beauty without corrective. The Greeks never pretend this is just another gift. In the oldest variants, Helen is the daughter of Zeus and Nemesis, not Leda. Her beauty is not merely attractive; it is retributive. It drives epics.

It starts early, a foreshadow of greater events. Theseus abducts Helen while she is still young. The violation is local. Theseus hides her at Aphidna, fortified, peripheral, plausible deniability in stone. The twins cross into Attica, sack Aphidna, recover their sister, and carry off Aethra in exchange. Justice here is reciprocal, archaic, unadorned. Only equivalence.

This is the only abduction of Helen cleanly undone.

Afterward the twins appear wherever heroes assemble, at Calydon, on the Argo, but they do not bend events. At the Calydonian Boar Hunt they are competent and narratively irrelevant. The hunt belongs to kin-murder and contested gifts; the twins do not fracture, so the story has no need of them. On the Argo, Polydeuces defeats Amycus in a boxing match so clean it leaves no residue (Argonautica 2.1–97). Castor stands beside him, unremarked. These are victories without aftermath, excellence without generational damage. Myth, which feeds on consequence, passes them by.

Their one story is small and final. Castor is killed in a feud with cousins, a death so unheroic it almost resists song. Polydeuces, suddenly confronted with surviving forever alone, refuses. He asks Zeus to share what cannot be shared. The solution is not resurrection, nor full apotheosis, but an arrangement: alternating days among the gods and among the dead, later imagined as joint placement among the stars.

This is fidelity carried as far as the structure of the world allows. Immortality is not condemned; solitude is.

By the time the Iliad opens, even this compromised presence has withdrawn. Helen, standing on the walls of Troy, scans the Achaean host and names those she recognizes, until she comes to her brothers, Castor the horse-tamer, Polydeuces the boxer (Iliad 3.236–244). She cannot see them. Homer provides the explanation with characteristic restraint: they are already dead in Sparta, held down by the earth. Whether this preserves an older tradition in which both were mortal or simply marks their absence, the effect is the same. The Trojan War is not a place for the Dioscuri.

That war is not about repair. It is about unburdening Gaia of the weight of too many heroes. It demands heroes who will not compromise, who carry imbalance to its terminus. The twins, whose defining act was refusal to outlive one another, belong to an earlier moral economy. They correct what can still be corrected and withdraw before catastrophe.

Rome, however, finds use for what Greece found too sober. In Roman tradition the Dioscuri appear as epiphanic horsemen at the Battle of Lake Regillus and are seen afterward watering their mounts at the spring of Juturna in the Forum. A temple is raised. They become patrons of cavalry, guarantors of oaths, figures of public concord. Where Greece left them half cult and half constellation, Rome anchors them in stone and ritual.

It is tempting to read this through Romulus and Remus, to see in the Dioscuri a divine mirror of Rome’s own founding twins. The sources do not insist on this, and we should not either. But Rome clearly thought in twins. Twin figures allow unity without singularity, power shared without dissolution. The Dioscuri offer Rome what Romulus and Remus could not: twins who do not end in murder.

In this sense they echo Virgil’s handling of Diomedes: Greek excellence displaced, not erased. Rome prefers figures who endure, who carry burdens forward, who accept limits without spectacle.

The Dioscuri never rule, never found cities, never end ages. They remain what they were at birth: divided gifts held together by loyalty. They are not tragic.

They are explanatory.

They tell us why the heavens behave as they do, not why humans fail to. That burden falls on Helen, on Clytemnestra, on the sisters who herald history rather than inherit the sky.

_______________

Later reception has decisively shaped how the encounter between Zeus and Leda is understood. The most influential elaboration is Roman. In Metamorphoses 6, Ovid stages the episode within the weaving contest between Arachne and Athena. Athena depicts scenes of order, hierarchy, and civic foundation; Arachne counters with a catalogue of Zeus’ transformations (bull, swan, golden rain) used to deceive and ravish mortal women. Ovid pointedly has Athena destroy the tapestry not because it is false, but because it is flawless: “Minerva could not find a fleck or flaw… enraged by such skill, she tore the web apart” (Ov. Met. 6.129). This Roman treatment aestheticizes divine excess and erotic deception. Earlier Greek sources are markedly restrained. In Pausanias and Apollodorus, the union is narrated without sensual elaboration, as a functional necessity required to generate the next cohort of figures who will advance the heroic cycle (Paus. Desc. 3.16.1; Apol. Lib. 3.10.7). Where Ovid titillates through spectacle, Greek myth proceeds by narrative necessity.

The asymmetry central to the Dioscuri appears already in naming. Polydeuces, Pollux in its Latinized form, becomes the dominant name in Roman cult, astronomy, and modern usage. The Greek Πολυδεύκης (Polydeukēs), plausibly derived from poly- (“much”) and a root associated with sweetness or delight, suits an immortal figure marked by athletic prowess and divine favor. Castor’s name, by contrast, is likely older and possibly pre-Greek, another quiet asymmetry the myth never resolves. Although some fragmentary traditions vary in details of paternity, the dominant early accounts preserve the core structure: one mortal, one immortal, bound together nonetheless.

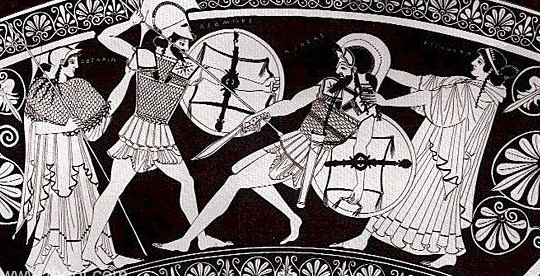

The fullest account of Castor’s death appears in Apollodorus (Apol. Lib. 3.11.2). The twins initially cooperate with their cousins, Idas and Lynceus, before a dispute over cattle and marriage claims to the daughters of Leucippus turns violent. The conflict is deliberately unheroic, centered on property. Castor is killed; Polydeuces retaliates; Zeus intervenes only once the asymmetry has been exposed. Pindar, in Nemean (10.55–70), suppresses narrative mechanics in order to foreground the ethical consequence: Polydeuces’ refusal to accept immortality alone and the resulting compromise of alternating existence. The episode establishes the Dioscuri as figures who do not resolve inequality, but refuse to abandon it.

This logic of correction appears most clearly in the early abduction of Helen. When Theseus and Pirithous seize Helen while she is still young and conceal her at Aphidna, the offense remains local rather than civic, geographically and morally displaced from Athens itself (Apollodorus, Library 3.10.7). The response is immediate and archaic: Castor and Polydeuces invade Attica, sack Aphidna, recover their sister, and carry off Aethra in exchange. The episode is resolved by equivalence, an early mythic economy in which wrongs can still be undone through symmetrical retaliation. It is the only abduction of Helen that ends in restoration, marking the last moment at which heroic excess remains correctable before catastrophe becomes irreversible.

If Helen initiates the Trojan War, her sister Clytemnestra defines its moral beginning and end. Married to Agamemnon, she is forced into the economy of heroic exchange when he sacrifices Iphigenia to purchase favorable winds. From that moment, her story becomes political rather than domestic. She governs in Agamemnon’s absence and consolidates power. When he returns, she kills him not in passion but in ritual, inaugurating the Oresteia. Aeschylus presents her not as a monster but as a coherent moral agent acting within an older logic of blood recompense that predates Olympian law. Her death resolves nothing; it intensifies the crime. By making vendetta unsustainable, Clytemnestra forces the transition from inherited violence to adjudicated justice. Helen initiates catastrophe; Clytemnestra compels the invention of law.

Rome, unlike Greece, finds enduring civic use for the Dioscuri. Dionysius of Halicarnassus records their epiphany at the Battle of Lake Regillus (Roman Antiquities 6.13–14), where they appear as mounted warriors fighting on behalf of the young Republic against the Latin League led by the exiled Tarquins. The same day, they are seen at the Spring of Juturna in the Forum, washing their horses and announcing victory (Livy, History of Rome 2.20). The episode is not merely miraculous; it is programmatic. Rome installs the Dioscuri at its political center as guarantors of oaths, patrons of the equites, and symbols of shared authority without kingship.

Roman use of the Dioscuri becomes clear when placed within Rome’s own compressed myth–history sequence. Rome begins with Aeneas, a refugee from Troy whose virtue lies not in founding but in enduring. His descendants rule as kings at Alba Longa until sovereignty collapses inward, producing Romulus and Remus.

The fratricide that follows is not arbitrary violence but a lesson staged in earth and law. Remus leaps over the newly traced fortification, violating the boundary that marks Rome’s first political act. Walls define limits. This gesture anticipates the Roman doctrine of the pomerium; the sacred boundary separating civic order from the space beyond, a line that could not be crossed by arms, magistrates, or the dead without sanction. (It is precisely this boundary that Julius Caesar violates when he leads troops across the Rubicon, an act that collapses the distinction between civic authority and military force, destroying the Republic and inaugurating the Imperium.) Rome would later deify Terminus, the god of boundary stones, whose immobility symbolized the inviolability of limits even to Jupiter himself. Romulus kills Remus not out of rage but to enforce a juridical principle: a city exists only where its boundaries hold. Rome is founded not on fraternity but on the sanctity of the line. From this follows Rome’s first and most durable political lesson: blood-based duality ends in fratricide, and kingship requires singularity. The early Roman wars against kings, both internal and external, are fought to formalize an alternative.

That alternative is the Republic. From 509 BCE onward, Rome governs through paired consuls, two magistrates holding equal imperium, each empowered to veto the other. This is containment: power deliberately fractured, rendered temporary, and stripped of inheritance. Dual authority is permitted only when it is elective, adversarial, and bounded by term. It is within this institutional logic that the Dioscuri find their place.

Where Aeneas embodies survival, and Romulus and Remus expose the fatal instability of kin-based rule, the Republic disciplines power through structure. The Dioscuri stand at the symbolic hinge of this sequence. They are not founders or rulers but confirmations. In anchoring them at its political center, Rome fixed in cult what it could sustain only imperfectly in history.

Astronomy clarifies the final distinction. Dioscuri (Διόσκουροι) means “sons of Zeus,” emphasizing paternity rather than fraternity. It is therefore misleading that later usage often calls them simply “the twins.” Twins describes their birth; Dioscuri describes their function. The name effaces the asymmetry on which the myth depends, treating Castor as divine by association rather than by paternity. This linguistic move is mirrored in the heavens themselves: the two principal stars of Gemini rise and set together yet remain visibly unequal, with Pollux consistently brighter than Castor. Greek myth does not correct this inequality; it dignifies it, translating unequal brightness into shared but compromised divinity.

This stands in deliberate contrast to the Near Eastern precedent. In Babylonian astronomy, the constellation later known as Gemini is identified with Lugal-irra and Meslamta-ea, equal and interchangeable gatekeepers of the underworld, preserved in texts such as MUL.APIN. Their significance lies in equivalence and procedural reliability. Greek myth replaces bureaucratic symmetry with relational inequality. In doing so, it transforms an administrative sky into an anthropological one.