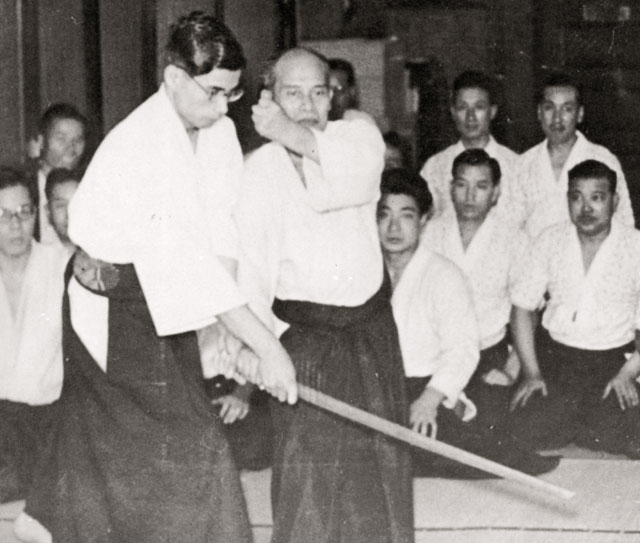

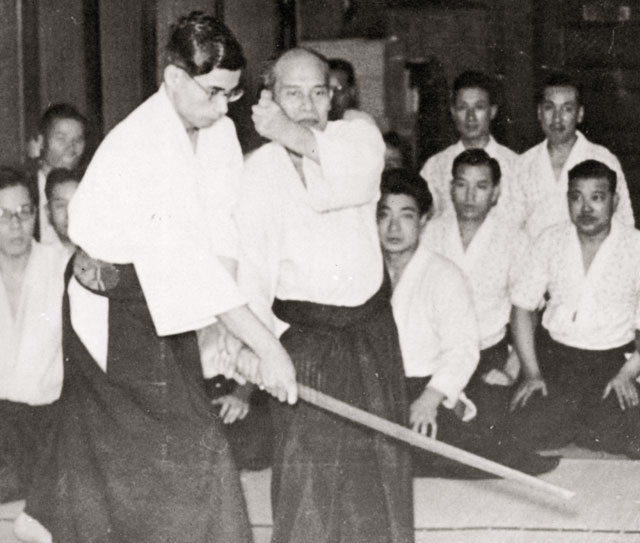

Mulligan sensei visited Portland Aikikai for a jō workshop (February 2019), the first seminar in the dojo’s new location. Portland Aikikai has the great benefit in long associating with Chris Mulligan who, from the dojo’s founding, was its primary weapons instructor.

YouTube for more by Mulligan Sensei

There are definite ‘styles’ in the use of weapons in Aikido primarily because the post war generation looked outside of Aikido for additional training. Saito sensei codified the 20 jo suburi and maintained the takemusu kumi-jo of Aikido at Iwama, but others expanded beyond that curriculum to augment their understanding and depth.[1]

In earlier posts, I have mused over the fact that the use of weapons is the foundation of the art, and that the empty-hand forms are nothing more than weapon movement stripped of the context of budo. Nevertheless, weapon work is usually an ‘advanced’ form of training in Aikido and it makes a certain amount of pedagogical sense: weapon work requires a higher degree of accuracy and mental focus.

As I watched during the seminar, it was clear that the basic handling skills are being transmitted, as are the forms. The next step is to cultivate and hone a sense of gravitas, a sense of directed purpose behind the movements.

How you approach training determines the results. If your goal is simply to learn form and follow the kumi-jō (or kumi-ken), then rote memorization is all that is required. Beyond the forms is bunkai, the application which requires a more serious level of dedication. For that, you need think about progression and your training should be focused on functionality.

Focusing on functionality requires that all the exercises and drills should simultaneously progress toward being able to apply what you are learning. Training should develop the ability to actually perform the technique. As an example in the jō, just ask yourself: can your covers truly receive a full power strike?

As you learn the form, if you are serious, you need learn application. Remember, the form follows the function! The forms are not empty kata, they are responses to strikes at directed targets! So do not become overly enamored of learning the sequence when you cannot actually receive a powerful strike or deliver one with martial vigor. The cultivation of the spirit of Budo is to be fully dedicated to the action of the moment: focused attention on what is necessary at that time.

This sounds simple, but it is easy to become distracted from focusing on application. You can get lost is a progression of drills and replication on the paired forms without ever learning how to use them.

Mulligan sensei focused on limited action-responses to emphasize application. If you are able to do each of the actions with purposeful determination then linking them in a sequence (8-count, shansho, any of the kumi-jō) becomes a logic-chain resulting in a continuous flow.

Remember, all of these cool flow sequences are made-up! In the good old days, you may have learned from a mountain Tengu, but the weapon forms in Aikido are all recent developments. There is no magic in the sequence – dissect the sequence and find each segment in the logic chain and be able to make that action work.

Often we can get distracted from the basic actions because a progression/flow sequence is simply more fun. Once we get familiar with a sequence it is fun to do it faster and continue to improve – but there is a pitfall in working on the flow to the detriment of efficacy. We can forget that the flow may be the ai-ki lesson, but the budo is in the stop-hit. Learn both and you are on the path to mastery.

Hence the need for a clear and purposeful training to learn the physical skills necessary to apply the art (bunkai) in addition to the memorization of patterns.

First emulate the teacher. The monkey-see monkey-do stage is inevitable, but it is only a transitional period to learn the basic movement pattern – the form. Learn to mimic and copy the form of skilled practitioners. Emulating correct movement patterns is the easiest way to begin to develop a mental model. Video footage is helpful – learning by watching others can help you develop the ability to visualize the technique. (And watching video of yourself is an amazing feedback device.)

Internalize the external visual presentation and you have your mental model. Now learn the purpose of the technique.

Mulligan sensei was explicit in showing the target (hit the thumb/forward hand) en route to the killing thrust. This is the importance and power of context – understanding the purpose. You need to know what to do, when to use it and why to deploy that technique. Everything has its purposeful place in time. You need to be able to gauge the success of your training in achieving the expected outcome. Understanding the technique’s purpose adds depth to your mental model: know the form and what it is for.

With the basic model of form and purpose developed, students now need to begin to feel the technique as applied. This is where I have seen the training methods change over the years.

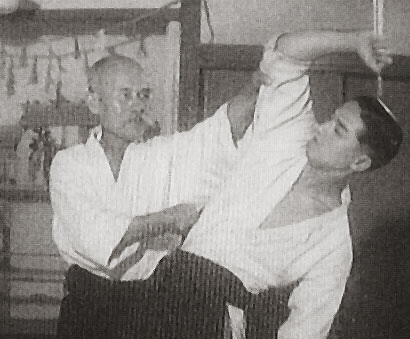

Although he did so only mildly during the workshop, Mulligan sensei would count out loud the number of times he hit me in training or during demonstrations. Yokomen, makiotoshi counter, striking my hand, “One.” Next strike, “Two.” Somewhat playful, but the lesson is real: learn to strike with earnest intent, learn to maintain contact, and be prepared to get hit. This requires fortitude. Are you willing to take a hit to better understand the technique? Pain as a teacher. It may be a necessary method to achieve excellence.

But there are ways to soften the blow. Look at the older video footage of Chiba sensei when he encouraged the use of hockey gloves to protect the hand, allowing full contact strikes. Proof of concept is in its execution at speed. You need to see and feel the technique. Visualizing the technique is the first step in internalizing the technique, but feeling it is the somatic integration.

You need to see the technique demonstrated correctly often so that you can maintain an image of it so you can hold it in your mind’s eye. Notice how Mulligan sensei developed a kata for the movement patterns in Sansho? If you can correctly see each node in the pattern, then linking the nodes becomes easier. But each number in the kata must be executed perfectly – pay attention to the footwork, body position, body mechanics and the hand movements. The kata will allow you to refine your skill and improve your ability to visualize. The easier you can visualize, the better you should be able to reproduce and instantiate the movements.[2]

While refining your mental model, the next state is to improve the quality of the mechanics – the raw physical deployment of the moves. The basic movement pattern needs to match your mental model but reproducing the movements consistently can only be done through repetition. Suburi is necessary – you cannot do 1,000 cuts incorrectly. The point is – push beyond your physical limits and the only way to continue to cut is with correct (effortless) form. You need to repeat that correct repetition until it is a habit – excellence is a habit.

Now add pressure – both mental and physical. Increase the muscularity of the strikes and the speed of the deployment. Do your mechanics break down – get sloppy? Progress until you can steadily gain in power and speed. Your visual acuity will increase as your mental model incorporates these variables – you should begin to compare your performance against the expected outcome. Did it work? It is your moral obligation to ensure that it does.

______________________________

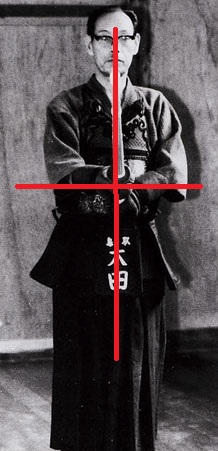

[1] Simply watch video of Saito, Yamaguchi, Saotome, Chiba, Nishio, Tissier sensei as an entry into the stylistic differences.

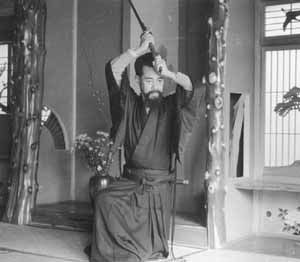

[2] Review Chiba sensei’s basic jo responses – and note the later incorporation into Shansho. But do note that these refinements are all derivative as is Chiba sensei’s batto-ho.

All Photos by Russ Gorman (except the Tengu)