Uchi komi is an exercise whereby a clear opportunity to attack is presented to allow for repetitive and correct training to recognize an opening and to strike.

In Aikiken, the basic uchi komi exercise opens with both uchidachi and shidachi in seigan no kamai. Uchidachi then lowers to gendan to invite shomen and when shidachi strikes, uchidachi receives by raising back to chudan level. The footwork starts migi-hanmi, slide to receive on the first attack, then each successive attack is with a step: L-R-L-R, etc.

Uchi komi teaches spacing, timing and connection. Spacing – uchidachi should start just outside simple range – from crossed kissaki, lower the sword to low guard and shidachi must still close to strike. Shidachi should be focused on the cut – the kissaki to strike shomen. Uchidachi must first maintain proper spacing (maai) to avoid being cut, and then bring the sword from low-guard to mid-line (or just above) to receive (‘find’) shidachi’s blade and control the center-line.

The body sequence for shidachi is attack – weapon, body, foot. Uchidachi is defense and therefore reverses the sequence, foot, body, weapon. This is a foundational (basic) exercise and is described in developmental (not application) sequence.

Shidachi has a ‘simple’ lesson to learn: observe the opening, orient on the target, decide to hit, then act by striking. Uchidachi must observe the strike, orient on space – retreat from the threat, decide to raise to guard, then act to find the blade. Uchidachi’s OODA loop is steps behind – and purposefully remains there! Typical strategy would be to interrupt the opponent’s loop to gain initiative, but uchikomi teaches a subtle lesson in timing and strategy: by creating the opening, uchidachi has directed shidachi to a specific target and therefore, uchidachi has seized the initiative before the action takes place (Attack By Drawing – ABD). In western fencing – strategy is paramount – mental chess – the game is to ‘make your opponent put his chest on the point of your sword.’ Uchikomi properly understood teaches the same lesson.

How do we get there? First a solid understanding of the biomechanics and physics. Shidachi should develop a command of a direct overhead strike. Easy to write, but not as simple to master. Uchidachi must always be cognizant of proper distance to avoid being skewered with a tsuki yet be able to deliver a lethal strike. Left hand is the power hand – right hand the guide hand – kissaki accelerating to the target area – free rotation from the shoulders, hands firm but not a death grip on the handle (‘like holding a bird, it cannot fly free, but you cannot crush it’), focused attention – all with a mindful awareness of the weapon – body – foot sequence and measure. Uchikomi allows shidachi to practice this proper sequence repeatedly.

Uchidachi must time the sequence (kimusubi) in perfect measure – maintaining a half a beat delay in action to ensure shidachi maintains commitment. Remember this timing difference is a bait, a draw. The act of raising from gedan to chudan is adamantly not a beat but rather a finding of shidachi’s blade. Uchidachi needs to connect and control the centerline. The very geometry of the katana facilitates this dominance, for as the blade is raised, the ‘belly’ of the sword is rotated toward shidachi’s ken, thereby forcing the opponent’s sword just off-line while uchidachi’s kissaki takes the center.

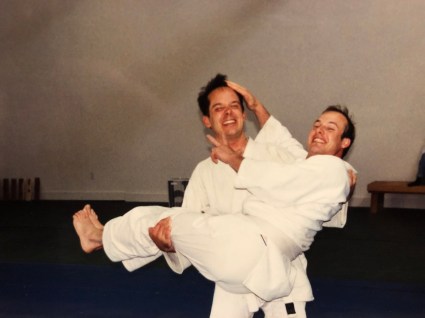

When I learned the exercise from Mulligan sensei, he would do it with shoulders and wrists relaxed, the control was through a fluid transfer of power with the hips – the sword retained the centerline and the body moved to either side of the sword. The primary focus was fluid motion – not catching the sword.

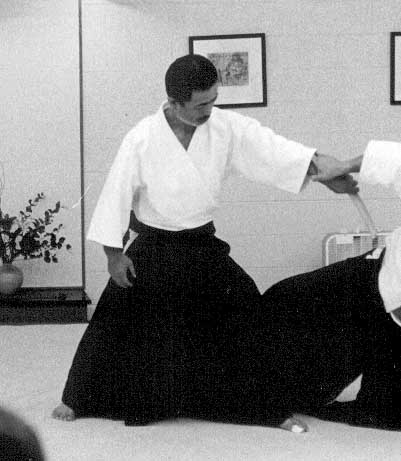

Shibata sensei taught it with a focus on the ‘capture.’ Once the blade is found, uchidachi would maintain a ‘sticky’ contact and then slide down to cut the tsuba with a determined ‘snap’ to emphasize the return to gedan with proper purpose. This has the added benefit of making it very clear which side of the blade will be used next to receive since uchidachi’s blade will end clearly either to the R or L position.

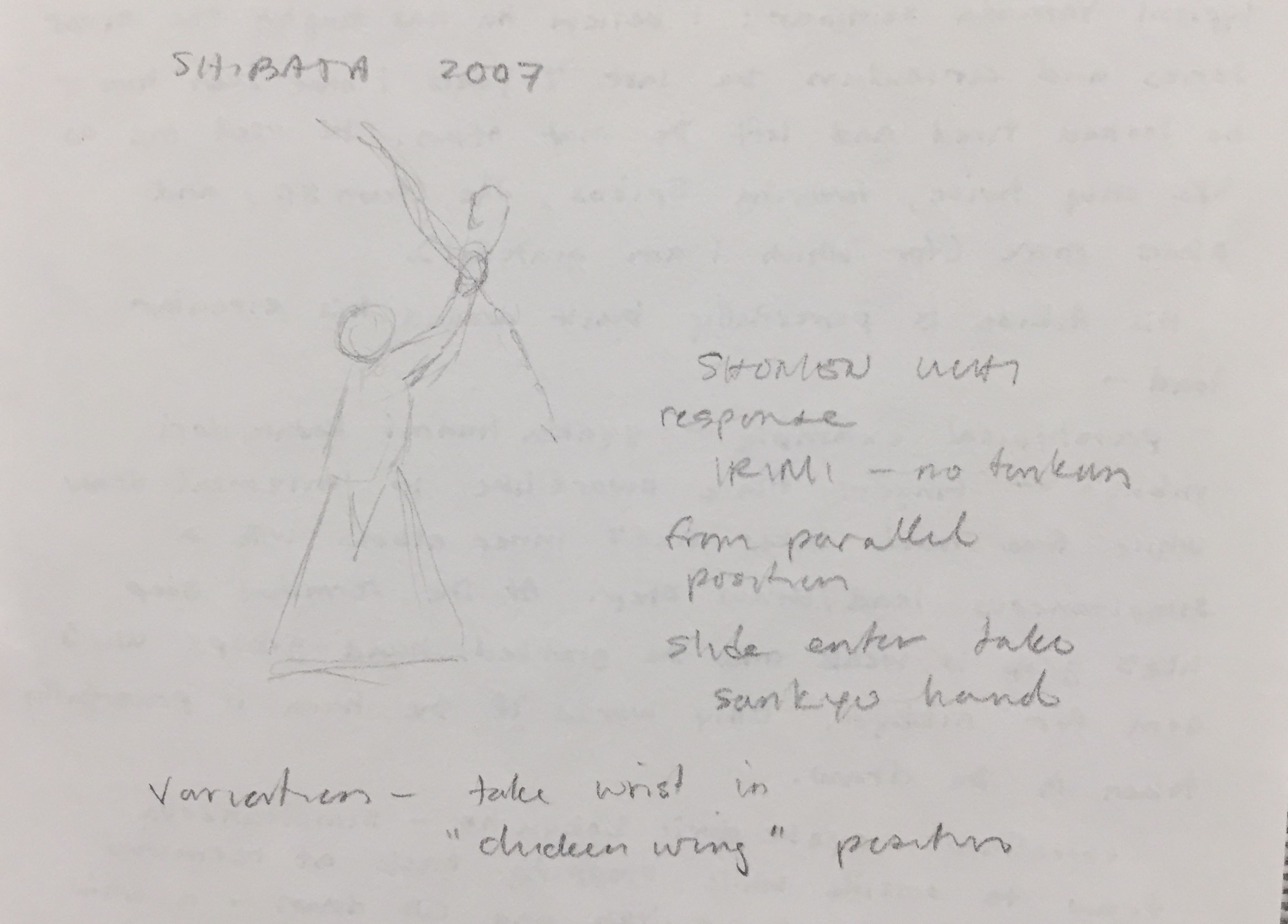

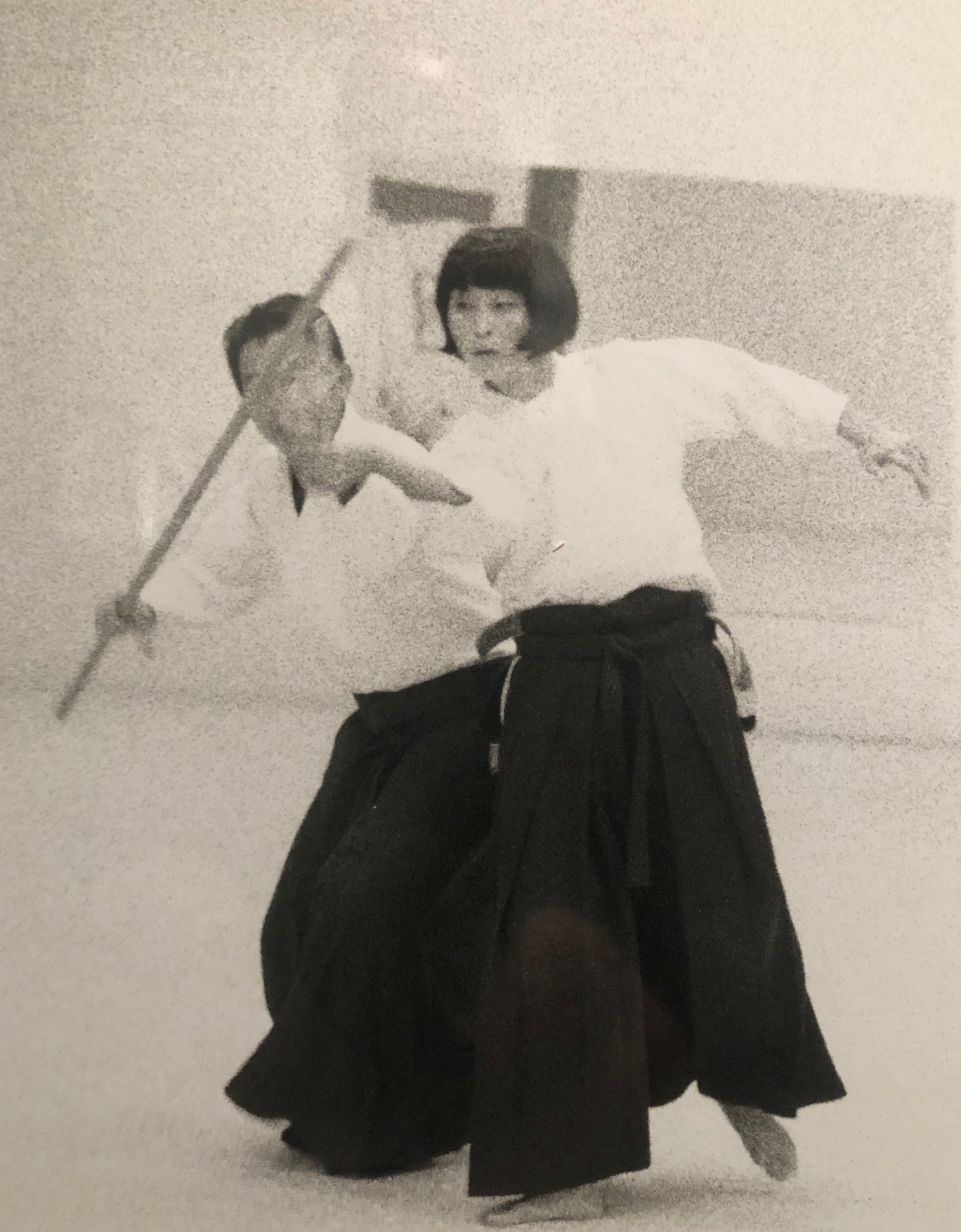

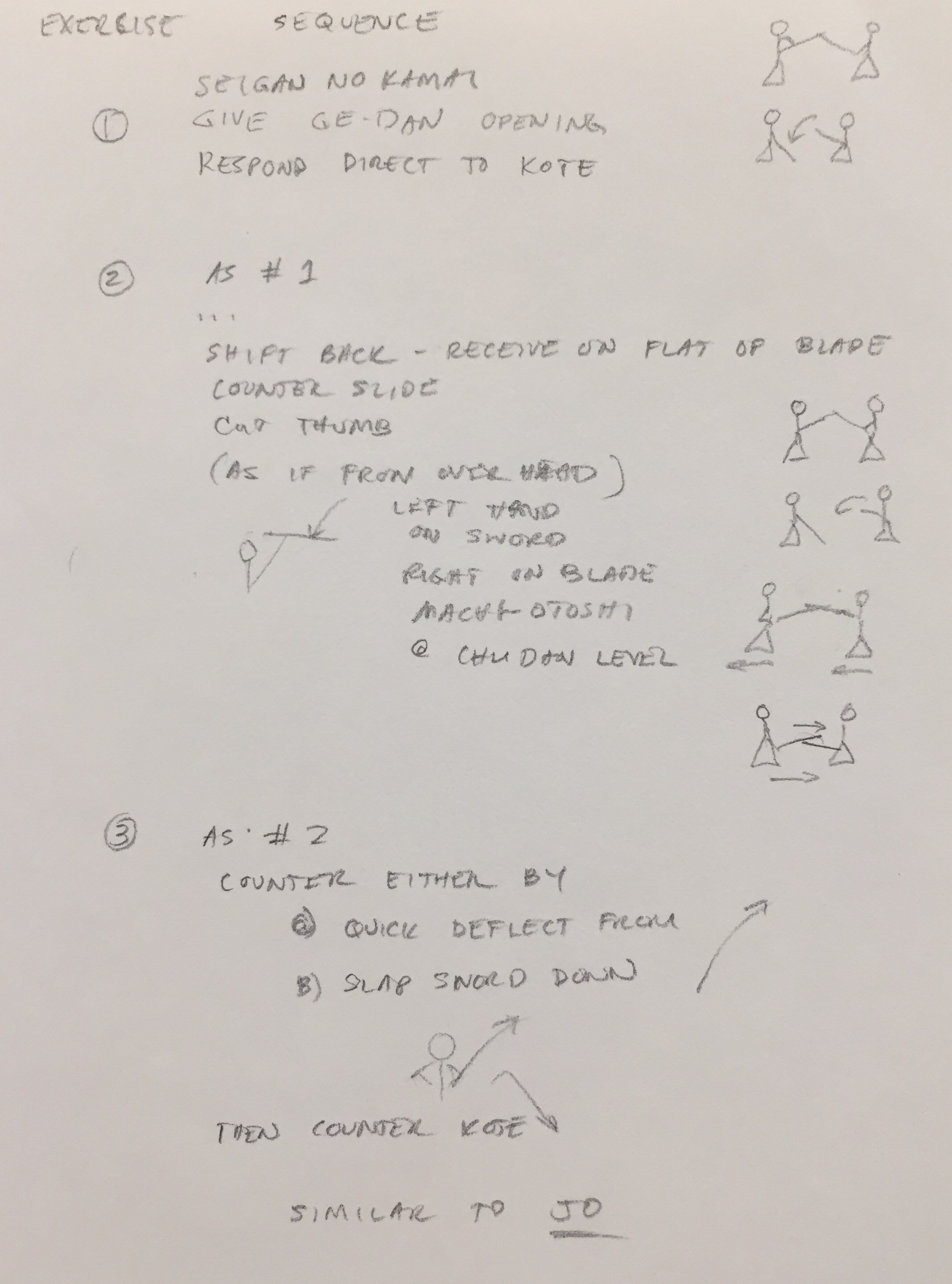

Reviewing notes – a more stationary version of uchikomi is shown below:

As shidachi strikes from an established maai, uchidachi remains ‘stationary’ (meaning the feet remain in their original position) but uchidachi uses a shinkokyu motion to remove his body as a target while bringing his sword from gedan to chudan but horizontal to the ground so that shidachi’s blade is captured at chudan level – having struck uchidachi’s ken perpendicularly.

From this structured position, uchidachi must take shidachi’s thumb with a spiral drop (maki otoshi) similar to the jo technique, but done only at chudan level and performed with the mechanical advantage of a lever but given power through the shinkokyu transfer through the legs. The right hand is a ball joint and the left is used to manipulate the kissaki (direct and accelerate it) while the legs provide the power. This exercise closes the distance, keeping both players in simple measure and forces a tighter connection. As a global analogy – the absorption is like using the rope-a-dope strategy.

When the exercises are combined, then encounter becomes full – in movement, uchidachi initiates the sequence (and dictates the attack!) by giving gedan, thereby opening his highline as a target. Shidachi attacks vigorously, and uchidachi responds by simultaneously finding the ken, deflecting its line, and cutting shidachi’s thumb and taking chudan tsuki. Reaction is faster than action? No – uchidachi was inside shidachi’s OODA loop from the first moment. The encounter was won before the engagement was made. No mysticism – just good tactics and biomechanics. The goal is to make shidachi put his thumb under your blade. This is a quick encounter – similar in spirit to kiri-otoshi which is played at jo-dan level. Uchi-komi is delivered on the rising line, kiri-otoshi on the descending line – but the deflection/dominance is the same just on inverse lines of approach.

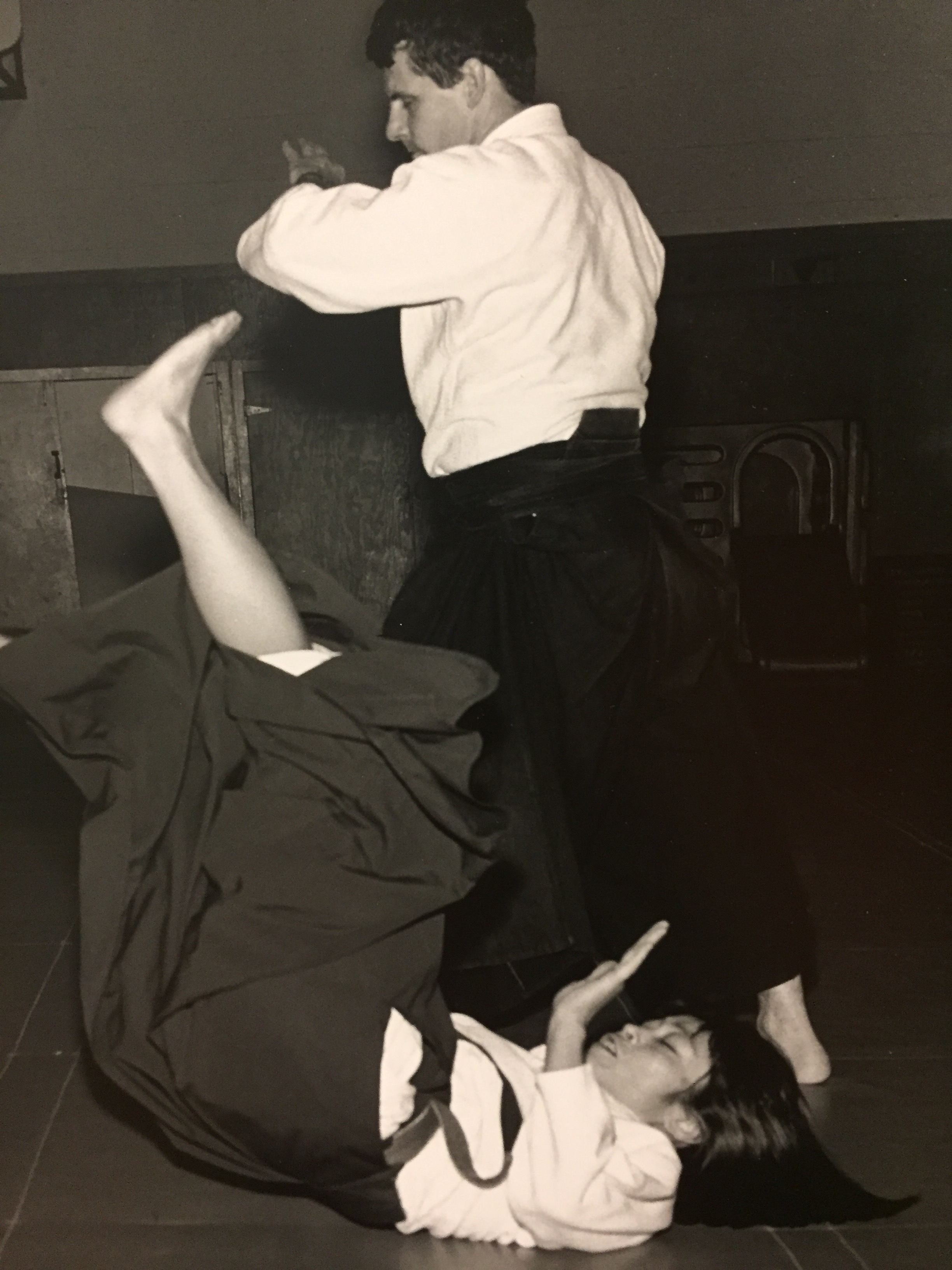

Done empty-handed, this is ai-hanmi katate-dori ikkyo done without foot movement – just the snap of the hips. Alternatively you could produce it ‘old school’ by replicating/emulating Chiba sensei in the early 90s when the emphasis was to draw uke in with the grasped hand’s palm coming flat to nage’s chest as nage circled in and forward before delivering the counter stroke to ikkyo – the hips coil like a watch-spring before releasing the potential energy. It is a close-quarter exercise, one designed for tanren-geiko – body development. Explore these training methods. There are important nuances to (re)discover – variations on how the shyuto is used (out, over, flat) but the fundamental movement and use of the body is the same. Know why the subtleties matter, but do not become overly concerned with ‘which is more correct.’ They all are important in order to have the skills to deploy in the moment when circumstances dictate.